Winter Camp, Part III

March, 1863

Edwin Forbes sketch, "Home Sweet Home, A Scene in Winter Camp."

- Introduction: What's On This Page

- MARCH, 1863;

- Boxes From Home; Two Letters of George Henry Hill

- A Walk Through the Muddy Camp of the Army of the Potomac

- Some of the Locals & "Protecting the Citizens"

- Corps Badges

- Two letters of Charles Adams

- A View From Headquarters, Army of the Potomac

- Shirks & Heroes

Introduction: What's On This Page

In March George Hill received a box from home and describes all the goodies packed inside. Private Noyes takes us on a long muddy trek through the camps of the Army of the Potomac over to General Hooker's Head-quarters. Sam Webster and Austin Stearns describe 'some of the locals.' Stearns gives a vivid description of 'Safe Guard' duty as performed by his friend Lyman Haskell of Co. K at the dreary home of Mr. & Mrs. Bullard. Charles Adams banters with his siblings back home in Boston about his tent-mates, officers, army reviews, picket duty, food, the weather and other matters. His 'laissez-faire' tone relegates military affairs to the background. At the end of the month, private Noyes, now a clerk at head-quarters reports on the condition of the Army of the Potomac from a broader perspective, as it prepares to open the coming Spring Campaign.

The exposition 'Shirks & Heroes' by Charles E. Davis, jr. ends the page and the section.

PICTURE CREDITS: All images are from the Library of Congress digital images collection, with the following exceptions: The photo of George Henry Hill is from his descendant Carol Robbins. The photo of Charles Follen Adams, is from Mr. Tim Sewell who shared these images from his ancestor James Lowell's scrapbook. The two engraved sketches in John Noyes' March 13th letter & the one engraved sketch in George Hill's March 21st letter of are from Sonofthesouth.com (Harper's Weekly) Charles Hovey, & Dr. Lloyd Hixon, are from from Army Heritage Education Center, Digital Image database, Mass. MOLLUS Collection. "Mr. Bullard," by Austin C. Stearns is from his memoirs, "Three Years with Company K," edited by Arthur Kent, AUP Press, 1976. Major Gould from Steve Heintzleman. The Charles Reed sketch of the potato candle was accessed digitally from the Book HARDTACK & COFFEE, by John D. Billings. The Laurel & Hardy sketch is by Wallace Tripp; John Best and family were shared by his descendant, Nancy Martsch. Walter Humphries portrait was downloaded from the inernet. Most of the drawings were done by Civil War Correspondent Alfred R. Waud. ALL IMAGES have been edited in photoshop.

MARCH, 1863;

On March 3rd, President Lincoln signed the 'Federal Draft Act,' effecting males between the ages of 20 -45. Physically and mentally unfit men were exempted, as were felons, men with certain types of dependents, and high state officials. The president set quotas by population. The number of volunteers already serving in each district was taken into account. A drafted man could purchase a substitute for $300.00. The measure increased volunteering.1

On March 10, Lincoln issued amnesty to soldiers who were Absent Without Leave. If they returned by April 1st charges of desertion would be dropped.2

At Headquarters, plans are being formulated, and corps-badges are introduced, (an idea of Hooker's chief of staff, General Daniel Butterfield). When John Noyes goes to clerk at Provost Marshall's Headquarters, he describes the condition of the Army as good, and preparing for the next move. Union Cavalry is re-organized to better compete with the Southern Cavalry. A Large fight takes place March 17, at Kellys Ford - more about that on the next page. In the Irish camps of the Army a huge St Patricks Day celebration is attended by the high mucky-mucks from HQ. It is not mentioned by George Hill or Charles Adams, who were probably on picket duty. John Noyes mentioned it in a letter not posted here.

"Yesterday was St. Patrick's day. A grand celebration was at hand in the Irish Brigade, Gen'l Meagher's, at which Gen'l Hooker and a large number of officers at Head quarters were present. Gen. Patrick accompanied Hooker."

The regiment sent back the state color it had been issued in 1861; The Adjutant General of Massachusetts, William Schouler received it March 9th. At 2nd Bull Run the colors were shot down five times in five minutes. At Antietam, nine of the ten men of the color guard were killed or wounded. The flag was replaced by another sent April 8th.3

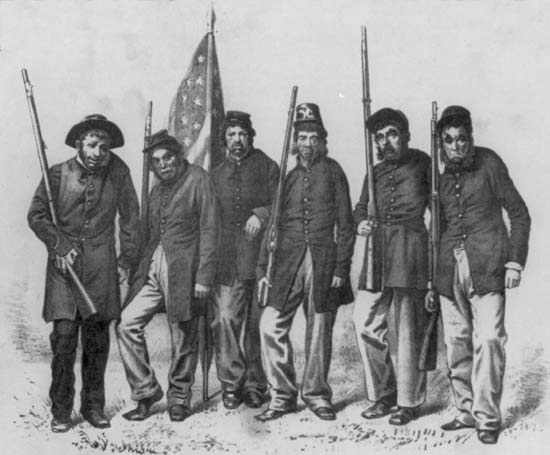

13th MassThe weather in March was still blustery, and it snowed at least 3 times. Below, George Hill writes about boxes received from home in-between picket duty. John Noyes takes a long descriptive walk through the muddy camps of the Army of the Potomac. He travels from Fletchers Chapel, to Head-quarters, to Belle Plain Landing and back again. Sam Webster lets us know its still snowing out as do the rest. Austin Stearns visits a friend doing Safe Guard Duty and describes some of the local residents in this part of Virginia. Charles Adams jokes with family members back home. Picket duty & drills are ever present. In March, Capt. Charles H. Hovey of the 13th, an inspector on General Taylor's Brigade staff, reported his own regiment as negligent in guard duty, wanting respect to officers, incompetency of officers &c. so strict orders were given to correct these defects!4

NOTES:

1. The Civil War Day by

Day, E.B. Long with Barbara Long,

1971, Doubleday & Co.,

re-printed by Da Capo Press. p. 325

2. ibid;

p.327-328.

3. This information is quoted directly from a paper prepared

by flag historian, Steven W. Hill, April 19, 1995, for the

Massachusetts State House flag collection.

4. Letter of John B. Noyes,

March 13, 1863, see below.

Boxes From Home; Two Letters of George Henry Hill

I am grateful to Carol Robbins, Hill's descendant, and Alan Arnold, for sharing digital images of these letters with me for use on this site.

Camp near Bell Plains Va.

Tuesday March 3d 1863

Dear Aunt Fanny

All of your letters have been received and I have been waiting for the box to come before I answered. Said box arrived Sunday and with the exception of one tumbler of jelly everything was all right.

The Oranges & Lemmons cocoanuts

cakes & candy were very nice only I expected there was more

cocoanut cakes and when I come across them I gave them to the boys who

were standing round and so had none for myself. but I had

enough else to make up for it. The bags were very

nice. I was a blunderer not to tell you the size,

but you guessed pretty near, size of a piece of chalk is good

! The scent bags we have hung

The Oranges & Lemmons cocoanuts

cakes & candy were very nice only I expected there was more

cocoanut cakes and when I come across them I gave them to the boys who

were standing round and so had none for myself. but I had

enough else to make up for it. The bags were very

nice. I was a blunderer not to tell you the size,

but you guessed pretty near, size of a piece of chalk is good

! The scent bags we have hung

P2

up over our heads to smell of. As for wearing them that’s played. When we first came out and before we knew the ropes it would have been different. I find dear Aunty that those who wrap up and dose up the most are just the ones who are continually sick or trying to be so in order to get a discharge from the service. Now as I do not want such a thing I shall keep all scent bags for their ligitimate [sic] use viz’ to smell of.

As for the bandages for the bowels they are good to clean our guns with and therefore quite acceptible. [sic]

So you know what the box

contained? Perhaps not so I will tell you.

So you know what the box

contained? Perhaps not so I will tell you.

Dead loads of doughnuts and mighty nice ones too. A lot of sugar cake. very nice… A role of sausage meat. A lot of shaker Apple sause. [sic] Four tumblers of nice jelly. alot of dried apples. Fry pan bags &c &c &c. and last

P3

but not least cocoanut cakes & candy Apples Oranges & lemmons. [sic]

John & I have been living high since the box came. The needle cases were first rate. John wishes me to extend his thanks to you for the case & also for the bags. Oh! I forgot I had a box of very nice butter too.

Of course I am very thankful for it all and it is needless for me to go into any great protestations to that effect.

We are still at our old camp and everything remains about the same. There are lots of rumors in camp to the effect that we are to be relieved by a new division and are to go back to Washington. I think there may be some truth in it as our division only numbers 4700 men. A full division is 15000. Col Leonard is in command of the division.

P4

I believe I have no more to write now and as I have to write to Adda I will close. I believe it is about time I wrote to Father.

With much love

From

“Bub-"

George's favorite Aunt, was taken aback by his candid teasing in the letter above, as the following letter shows.

Camp near Bell Plains.

Saturday Mch 21/63

My dear Aunt

I received a letter from Mother to night

in which she says she has been down to see you and found you feeling

quite hurt at what I wrote in my letter about the bandages

&c. It is

quite late to night, but I start tomorrow

to go on picket for three days and therefore I must write now or not

until I return and as I now feel hurt that you should feel offended at

my nonsense I must attend to it now. So you feel hurt do you,

and for what? because

It is

quite late to night, but I start tomorrow

to go on picket for three days and therefore I must write now or not

until I return and as I now feel hurt that you should feel offended at

my nonsense I must attend to it now. So you feel hurt do you,

and for what? because

P2

I did not write to you that the bandages were just the right things at the right time? And would you have me write that while at the same time I thought entirely different? Of course not.

I appreciate your kindness in sending them and all that but it is difficult to persuade an old soldier to adopt anything that is not absolutely necessary.

But to please you I will now put them on.

There ‘tis done. first the spice bag and then three of the bandages one over the other and I guess now my life is safe at least from any danger from diareah. In future I must be more cautious of how I write to you, I thought you knew me well enough to take my fun just as it was sent

P3

and not wish me to prevaricate in order to make everything move just so nice. I will do better in future. How is this?

“The spice bags and bandages were just what I wanted and I have no doubt I shall find them very efficatious,”

Do you like that better?

But aside from joking believe me I appreciate your kindness and good heartedness in sending them just as much as though I used them and had I have thought it would have pleased you I would have surely worn them. I wait anxiously for a letter from you containing my forgiveness for my seeming unkindness for believe me it was farthest from my thoughts to do anything to hurt the feelings of my dear

P4

Aunt Fannie. I am hurt however that you should for a moment think such a thing possible.

Excuse haste

Accept with much love from your penitent nephew

Geo. H.

A

Walk Through the Muddy Camp of the Army of the Potomac

Letter of John B. Noyes; By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Camp 13th Regt. Mass. Vols.

Near Fletcher’s Chapel Va. Mch 13 ‘63

Dear Martha

Your letter or rather Mother’s of the

8th inst & George’s of

the same date reached me last evening. The photographs are

not very

distinct, but will do.

Matters about camp are as usual, save that greater strictness

prevails. The truth is that Capt. Hovey of our Reg’t.,

inspector on Taylor’s Brigade staff reported our Regiment as negligent

in Guard duty, wanting respect to officers, incompetancy of officers,

&c, so that strict orders have been given to remedy these

defects. On account of the configuration of the ground on

which our camp is pitched, regularity is hardly to be attained, and a

street only a yard or two wide only intervenes between the

companies. Aside from this however the camp ground looks well

enough and is Kept clean, although to be sure a few chips generally lie

round, as there is more or less chopping going on from reveille to

taps. The chips however are daily carried away. Truth to say

the guard duty has been rather slack lately, by whose fault I can’t

say. Whether it can be remedied I can’t say. The

salutation oftener made to the back than to the face of Capt. Hovey

(Brig. Gen. Pill-box) alluding to his apothecary business, perhaps

account for the charge of want of respect to officers, though I must

confer I do not think the officers are treated with sufficient

courtesy, so far as touching hats is concerned. (Captain Charles H. Hovey,

pictured).

Matters about camp are as usual, save that greater strictness

prevails. The truth is that Capt. Hovey of our Reg’t.,

inspector on Taylor’s Brigade staff reported our Regiment as negligent

in Guard duty, wanting respect to officers, incompetancy of officers,

&c, so that strict orders have been given to remedy these

defects. On account of the configuration of the ground on

which our camp is pitched, regularity is hardly to be attained, and a

street only a yard or two wide only intervenes between the

companies. Aside from this however the camp ground looks well

enough and is Kept clean, although to be sure a few chips generally lie

round, as there is more or less chopping going on from reveille to

taps. The chips however are daily carried away. Truth to say

the guard duty has been rather slack lately, by whose fault I can’t

say. Whether it can be remedied I can’t say. The

salutation oftener made to the back than to the face of Capt. Hovey

(Brig. Gen. Pill-box) alluding to his apothecary business, perhaps

account for the charge of want of respect to officers, though I must

confer I do not think the officers are treated with sufficient

courtesy, so far as touching hats is concerned. (Captain Charles H. Hovey,

pictured).

Take our Regt out in inspection however, and sabe(?) that mind your own business habit of well taught soldiers, our regiment Keeps up to the old standard. In personal cleanliness, in the display of polished shoe leather & well dusted uniforms, as well as thoroughly cleaned guns, in perfect order, ready for action no regiment here abouts is equal to ours. I doubt however whether the brasses have that immaculate polish which distinguished our regiment from others in Gen’l Banks’s Div. while at Darnestown, Md. some 15 months ago. The regiment still retains its old pride, Knows its capabilities, and with an incentive before it would distance any regiment in the brigade or Corps, as it did at Darnestown, Md. where were stationed the 2d Mass., and 3d Wisconsin, well Known regiments and celebrated for their efficiency. Talk about demoralization, I never Knew a time when the Reg’t was less demoralized.

Mother wants to Know what I

received of Mr. Gaylord’s

bounty.

One pair of mittens. I am glad to hear that father’s teeth

suit him so well, and that Stephen is in a fair way to afford a set

when he becomes toothless. I told Quartermaster Welles that

his brother

was now in Cambridge. He said he must get a furlough and

spend a few days with him. Lieut. Welles is in excellent

health. I see by Mother’s letter that George has been

bombarding the

State House again in my favor. With his diversion in front

and my iron clads in the rear of which I spoke in a late letter to

father I think the Governor will be obliged unconditionally to

surrender. Be that as it may I have no fears upon the

subject. I have concluded to

leave the Reg’t. for a time and

go to the Head Quarters of the Army. In other words

acting

under the impression that I shall leave the Army within a month’s time,

and by the advice of friends I have accepted a clerkship in the office

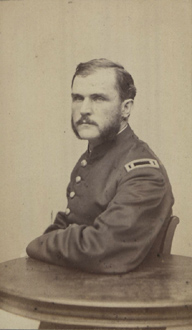

of the Provost Marshall General Patrick (pictured) at the

Head Quarters of the

Army of the Potomac tendered me by the Asst. Adjt. Gen’l. J.P.

Kimball.

I have concluded to

leave the Reg’t. for a time and

go to the Head Quarters of the Army. In other words

acting

under the impression that I shall leave the Army within a month’s time,

and by the advice of friends I have accepted a clerkship in the office

of the Provost Marshall General Patrick (pictured) at the

Head Quarters of the

Army of the Potomac tendered me by the Asst. Adjt. Gen’l. J.P.

Kimball.

How it happened that my name was given to Capt. Kimball as that of one desirous to obtain a clerkship I am unable to say. I wrote him as much and accepted the detail. The detail will probably reach me tomorrow when I shall change my quarters for a season. I suppose Mother will be glad, as a clerk in the Provost Marshall’s office is not generally ordered out to assist in a forlorn hope, or to be sent out to be one of a party to drive in the enemy’s skirmishers on the eve of a decisive battle. I walked over to General Patricks Head Quarters to see Capt. Kimball yesterday, and for want of something better to write about, and as the narrative may not be without interest to you, I will give you an account of my journey.

The Army Headquarters are

probably six or seven miles from here,

perhaps further. Provided with a pass from the Major I set out taking

the road to Falmouth. There are no pickets in this woody

country & the roads are consequently little else than mud

holes. One who does not wish to go over boots in mud holes is

careful to walk by the side of the road, even going out of sight of it

occasionally to avoid the mire. The different Brigades and

divisions of

the Corps of the Army of the Potomac are scattered here and there over

the country, consequently there are many cross roads, and it is

difficult to find ones way, such road being equal to the other in depth

of mud. The main road however is corduroyed, although the

logs in many parts of it are covered with a layer of mud six or eight

inches deep. In many portions of the road piles of logs lay by the way

side to be used to corduroy it.

In many portions of the road piles of logs lay by the way

side to be used to corduroy it.

(The photograph at left shows a corduroy road).

No one could tell me where Gen’l. Patrick’s Head Quarters were for some miles. At last I met a mounted orderly who told me to follow the telegraph wire, and I would not miss my way. I did so and Erelong found myself in Gen’l. Patrick’s tent. Having transacted my business I departed, walking by way of variety, to feel how it felt, on a plank road walk which surrounded an enclosure of over an acre in extent on which fronted countless wall tents of officials of the Army of the Potomac. Here I saw guard duty performed in style.

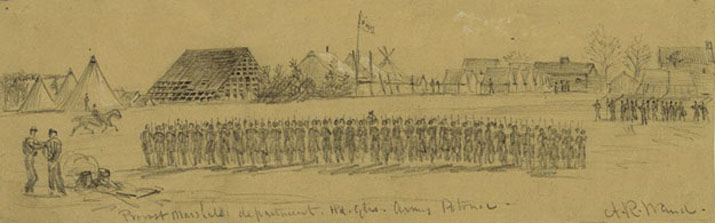

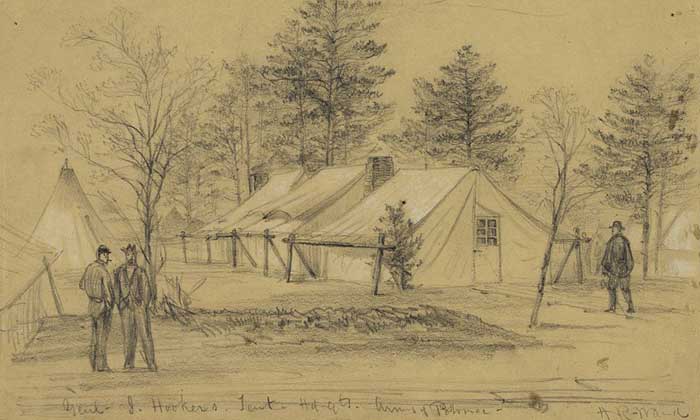

Pictured below is a sketch by artist A. R. Waud of the Provost Marshall's Department, Head-quarters, Army of the Potomac, March, 1863. This is where Private John Noyes visited General Patrick.

On my way back I was questioned several times with respect to the road to Head Quarters of the Army, Belle Plain Landing, & Reynold’s Corps, and I was able to say to all, Keep an eye on that Telegraph wire and you will not loose your way. Ten to one they asked someone else shortly after and were directed wrong.

Pictured is the Adjutant General's tent at Head-quarters, Army of the Potomac, (Falmouth, VA) as sketched by A. R. Waud in March, 1863.

I soon met a

companion on the road, a member of the 2d Sharpshooters who was on the

way to my corps to see a brother in the 24th Mich. He had

borrowed a horse to expedite his journey. He told me however

that he thought he should have done better had he walked as the going

was so bad. Indeed a horseman here avoids the road and picks

his way like a foot traveler, through wood and swamp, fearful only of

sinking in the muddy road. Every thing went on well for a

time. The

sharpshooter got a few rods ahead of me while I made a cut across the

country.  As

I came up to him I found him endeavoring to raise

his horse which had got stuck in the mud beyond extrication.

I helped him for a while. The forelegs of the animal were

buried therin whole length, the hind legs were in deeper and deeper the

harder it tried to recover itself. I suggested to the soldier

to get a spade at a house nearby to dig the horse out if that were

possible. After tarrying for half an hour or more I took up

my line of

march. When I left the soldier was digging away at extremely

heavy mud, mud so heavy that he could scarcely extricate himself after

his exertion. The task seemed endless. The horse

had been lying for a quarter of an hour on his side in the mud, his

head & neck in the mire, saddle, bridle &c covered with

mud. My friend of the 2d Sharpshooters had gone over 14 inch

top boots

in the mud and his overcoat was becoming heavier and heavier with mud

as the moments flew by. I forgot to suggest to him to take of

his overcoat when he began to work on the horse, and he was too busy to

think of it himself.

As

I came up to him I found him endeavoring to raise

his horse which had got stuck in the mud beyond extrication.

I helped him for a while. The forelegs of the animal were

buried therin whole length, the hind legs were in deeper and deeper the

harder it tried to recover itself. I suggested to the soldier

to get a spade at a house nearby to dig the horse out if that were

possible. After tarrying for half an hour or more I took up

my line of

march. When I left the soldier was digging away at extremely

heavy mud, mud so heavy that he could scarcely extricate himself after

his exertion. The task seemed endless. The horse

had been lying for a quarter of an hour on his side in the mud, his

head & neck in the mire, saddle, bridle &c covered with

mud. My friend of the 2d Sharpshooters had gone over 14 inch

top boots

in the mud and his overcoat was becoming heavier and heavier with mud

as the moments flew by. I forgot to suggest to him to take of

his overcoat when he began to work on the horse, and he was too busy to

think of it himself.

Traveling on I soon came upon a wagon train loaded with forge under the charge of a cavalry sergeant. The teams were driven by negroes. One of the teams had met with an accident. In a very bad spot in the road where the mud varied in depth from ten to twenty inches the tail board had tumbled out followed by two bundles of hay. The teamsters of the first two teams of the train were bawling out to the other teamsters in the rear who like one of Mother’s old friends could hear anything it was agreeable for them to hear, but who were as deaf as haddocks to their outcries. Soon was heard the command of the Sergeant who chided the darkies telling them they Knew very well they had the job to perform and might as well come now as ever. Up came the darkies and soon one of the bundles was on the teams. What looking darkies! Covered with mud in front from head to foot. Soon the 2nd bundle also was placed on the baggage wagon. All the time the darky who drove the damaged team looking on with his mouth stretched from ear to ear displaying a fine set of ivories for my benefit and chuckling and remarking “dat berry well. You do very well when I observe you, Yaw, Yaw, Yaw.” He was careful also to jump the place the others were obliged to wade through where the mud was over boot tops. Carrying the negro’s visage along with me, and wondering from whose plantation the dead beat had strayed, I Kept my eye on the telegraph wire steadily.

Soon however I turned my eyes in wonder at the water and found that I was at Belle Plain Landing, the terminus of the telegraph wire. I had taken the wrong road, or rather had not left the wire at the right place.

View of Belle Plain Landing - the dock is in the center background. The photo is undated but several photos of this place were taken in 1864. Its probably safe to assume this was taken the same time.

I know I was just three miles from

camp. But

it was impossible to tell which of the many roads lead to Robinson’s

Division. Finally I saw a mounted orderly who directed

me. In return I directed him to the Regiment of Lancers,

stationed near the Landing* (*Noyes

wrote Lancers - I am guessing he meant Landing.)

Soon I came upon the

Regt of the

33d New York, I believe. The Col. was having battalion

drill. His voice was stentorian. The men evidently

needed

drill to judge from an order arms I heard rumbling like the noise of

distant thunder and quite as much prolonged. Passing through

the camp I enquired the way to Gen’l Reynold’s

Headquarters. No one could tell.  A horseman pointed

out the road however, but he was out of sight soon and there were many

branch roads. I was soon out of my reckoning. No

one could tell where Gen’l Reynolds head quarters were. At

last I found a teamster who thought Reynolds must be out on a certain

road. He said there was a sign post at the cross-road, which

post I could distinctly see which might perhaps tell me. He

had driven by it a hundred times, but had’nt noticed what was on

it. He would next time. The sign post had printed

out in full, Gen’l Reynold’s Head Quarters 1st Army Corps. I

walked in the direction pointed out and was soon at the door of the

tent of a member of Co. B who was there stationed as one of the

Corporals of the Head Quarters Guard. Before I went in I

stopped to hear the distant commands of the stentorian voiced colonel

of the 6th Corps whose regiment needed drilling in order arms.

A horseman pointed

out the road however, but he was out of sight soon and there were many

branch roads. I was soon out of my reckoning. No

one could tell where Gen’l Reynolds head quarters were. At

last I found a teamster who thought Reynolds must be out on a certain

road. He said there was a sign post at the cross-road, which

post I could distinctly see which might perhaps tell me. He

had driven by it a hundred times, but had’nt noticed what was on

it. He would next time. The sign post had printed

out in full, Gen’l Reynold’s Head Quarters 1st Army Corps. I

walked in the direction pointed out and was soon at the door of the

tent of a member of Co. B who was there stationed as one of the

Corporals of the Head Quarters Guard. Before I went in I

stopped to hear the distant commands of the stentorian voiced colonel

of the 6th Corps whose regiment needed drilling in order arms.

The camp lay just over a high hill a stone’s throw away. I had been only about an hour absent from said camp. After resting myself I set out for the 1st Main Cavalry. I was soon in the camp of the 1st Penn., Cavalry, I think, I enquired there where the 1st Me. Camp was. The answer was “I don’t know. What camp is that, there” pointing my finger to a camp into whose grounds I could almost cast a stone. “Can’t tell” the answer.

I walked a few rods and soon found myself in the tent of Lieut. Myrick, H.U. (Harvard University) Class 1858, of the 1st Me. Cavalry. His father was in the tent also. We had a pleasant chat together till darkness coming on I left him. In some way he had been cheated out of his tent & had only a fly with blankets at each end logged up. The tent was far inferior to mine, Cold & cheerless, all the more from contrast with other tents. The Maine Cavalry has been very hard worked this winter, or rather 3 days on & 3 days off, which in practice amounts to what I first stated. I told Myrick we thought 2 on 10 off pretty rough, but as they say at home join the cavalry & you don’t have to go afoot on marches.

From the camp of the 1st Maine to Div. Head quarters was but a short walk, from there to my tent a shorter. It was snowing pretty fast when I entered my shebang and I was hungry enough to appreciate a cup of tea, toasted bread & butter and a plate of baked beans topped off with molasses cakes and dried apple sauce.

About a week ago Dr. Hixon

joined the Regt. as

Ass’t Surgeon. He used to teach in the High School in Lowell.

I think you saw him at a little party at Aunt Martha’s a few winters

ago. He sent for me and I recollected him. He has

since

called on me two or three times. He is a very pleasant man indeed

though a little deaf. [Dr.

Hixon, pictured, right] Tomorrow I leave the

Reg’t.for Gen’l

Patricks head quarters. When I get there I will write my new

address,

as I shall want Co. B.13th Mass. left off my letters in the future else

they will be delayed two or three days on the road.

About a week ago Dr. Hixon

joined the Regt. as

Ass’t Surgeon. He used to teach in the High School in Lowell.

I think you saw him at a little party at Aunt Martha’s a few winters

ago. He sent for me and I recollected him. He has

since

called on me two or three times. He is a very pleasant man indeed

though a little deaf. [Dr.

Hixon, pictured, right] Tomorrow I leave the

Reg’t.for Gen’l

Patricks head quarters. When I get there I will write my new

address,

as I shall want Co. B.13th Mass. left off my letters in the future else

they will be delayed two or three days on the road.

Provost Marshal General’s Office

Headquarters Army of the Potomac

March 14th

My direction now is

“Mr. John B. Noyes, care of Gen’l.

Patrick

Provost Marshal General,

Headquarters Army of the Potomac.

Tell father to send me ten dollars by the next mail, one five the rest in small bills. I may need the money supposing I receive orders to go home soon, and shall need the money if I remain. Tell Charles of the change in my address.

Your Aff. Bro.

John B.

Noyes.

Some

of the Locals & "Protecting the Citizens"

Diary of Sam Webster

Excerpts of this diary (HM 48531) are used with permission from The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA

Thursday, March 19th, 1863

Division reviewed by Brig. Gen. Jno. C.

Robinson, the new Div.

Commander. [pictured,

right] 13th best looking regiment in the line – had

bought out the sutler’s stock of paper collars.

Friday, March 20th, 1863

Snowing beautifully, otherwise we would

have been reviewed by

Gen.

Reynolds today. Our camp in on a point of land (east of the

residence of a Mr. Bowie, ex-sheriff), between two small streams

running north and joining a few hundred yards from camp. All

the wood which was near us having been cut off, we go away down this

stream for fuel, sometimes over a half-mile, lugging it on our

shoulders to camp. Water is good. Bowie’s is one of

the few respectable families in the neighborhood; tho’ within a mile

there are huts of some eight or ten families, commonly known as “pore

white trash.” They live in houses, 18 or 20 feet square,

built of logs, one room below, attic above. One door, seldom a window,

chimney built by running logs back at one end, and plastering heavily

with mud to keep them from burning. When finished out with a barrel the

chimney is complete. Stoves unknown, but Dutch ovens are used

for baking when the ashes are not. Floor generally of slabs,

when

anything better than bare earth is aspired to. The men all

look as if the fever and ague were the “chief end of man,” and the

women all wear bed ticking – tho’ that is the result of the war, partly

– and dip snuff. Corn bread is their diet so far as learned,

but one family has a garret full of chickens. Scores of

answers to Jack Leonard’s advertisement over name of Edw. Danforth, for

correspondents.

Protecting the Citizens

From "Three Years with Company K"; 1976 Fairleigh-Dickenson Press; P. 157-162. Used with permission.

When we came here in Dec. the citizens asked for a man to come to their houses and stay to protect their property; they were called safe-guards. Our company furnished three. Bruce went to a widow womans with three grown up daughters, about a mile and a half away, Haskell to a family named Bullard, in the same direction but in plain sight of our camp, and John Stearns went in another direction about a mile away. Bruce and Haskell staid all winter, and John till he was detailed at Corps Headquarters.

I used to go up and see John, and once in a while would bring back a “Pone cake” for my trouble. Pone cake was corn meal rolled into a piece of dough about as big as my two fists and baked in a pot.

I used to go over and see Haskell, but never to eat. I recollect of being over there one afternoon and Haskell invited me into the house. I accepted, and as this is a good representation of a great majority of the poor white establishments, I will give it.

The house was simply a log house about fifteen feet square, containing one room with a door on either side; for a window there was a hole about two feet square with a sliding board in the inside to stop it up when needed. The fire-place and chimney were built on the outside of the house of sticks and mud in regular Virginia style. In one corner of the room on the opposite side from the fire-place stood the family bed. In the corner on the left of the fire-place stood a table, in the center of the room was a bench about four feet long used for a seat, [and] there was two chairs without backs, or stools, I have forgotten which. When we entered Mr Bullard sat on one, and Mrs B – the other, while the five children, the eldest a girl of fourteen, sat on the bench, or floor. On being introduced Mr B – arose, shook hands, and invited me to take a seat, offering at the same time his stool. Mrs B- arose, courtesied, [sic] and resumed her seat. Declining with thanks Mr. B- offer of his seat, I said “I would sit with Haskell on the bench.”

We sat facing the fire, with Mr

B- on our right and

Mrs B- on the left and near the fire; the children were scattered

promiscusly [sic] around. I now noticed why Mrs B-

sat so near the fire; she was preparing a meal for them, and the pot

was over the fire in which was their “pone cake,” also a frying-pan in

which, swimming in its own fat, was the ever to be found

“smoked sides.” On the hearth were two old tin cans (such as

the boys had bought can fruit of the Sutler in) in which she was making

coffee. Mr B- was chewing tobacco, and spitting into, or

rather towards the fire, [and] as he sat some distance away, many were

the times that he failed of his mark and there was a stream between him

and the fire. We entered into a general conversation, for he

was quite an intelligent man and was very well informed in some

things. Of course he knew nothing about the resources of the

rebels, or their condition even, all this was mere speculation with

him, but he could talk like a man that knew it all, and he had great

confidence in the success of their cause and that they never would be

conquered, but would gain all they wanted in the end. To my

enquiry of where he based his opinion, he said “that the south would

never submit to Yankee rule, they would never be conquered,” without

giving any reasons. Not wishing to excite him too much, I

refrained from talking any more about the war.

We sat facing the fire, with Mr

B- on our right and

Mrs B- on the left and near the fire; the children were scattered

promiscusly [sic] around. I now noticed why Mrs B-

sat so near the fire; she was preparing a meal for them, and the pot

was over the fire in which was their “pone cake,” also a frying-pan in

which, swimming in its own fat, was the ever to be found

“smoked sides.” On the hearth were two old tin cans (such as

the boys had bought can fruit of the Sutler in) in which she was making

coffee. Mr B- was chewing tobacco, and spitting into, or

rather towards the fire, [and] as he sat some distance away, many were

the times that he failed of his mark and there was a stream between him

and the fire. We entered into a general conversation, for he

was quite an intelligent man and was very well informed in some

things. Of course he knew nothing about the resources of the

rebels, or their condition even, all this was mere speculation with

him, but he could talk like a man that knew it all, and he had great

confidence in the success of their cause and that they never would be

conquered, but would gain all they wanted in the end. To my

enquiry of where he based his opinion, he said “that the south would

never submit to Yankee rule, they would never be conquered,” without

giving any reasons. Not wishing to excite him too much, I

refrained from talking any more about the war.

Mrs B-, with the assistance of her daughter, had by this time set the table with two platters, or deep dishes, and poured the greesy contents of the frying pan into one, and placed the pone cake on the other, [then] announced that the meal was ready. Mr B- arose and politely invited me to a seat at the table with him; I as politely declined, giving as my reason that I had just eaten as I left camp. It was not often that we had a chance to sit at a table and we seldom refused, but the thought of the tobacco juice from Mr. B- mouth satisfied me, without knowingly partaken of it. Mr. B- then drew his stool up, and Mrs B- turning on hers, the children standing around and seeking the most advantageous position.

The meal was commenced by each one taking a piece of the cake and dipping it in the fat before eating it. They were not over careful about spilling the fat on the floor or on themselves. While they were at their meal Haskell and myself talked together. After eating everything that was cooked, and drinking the coffee, the old man went back to his side of the fire place, and producing a dirty looking pipe, filled it, and taking a coal from the hearth lighted it. After smoking away for a few moments [he] passed it to Mrs B-, who, after indulging in a few sweetly pleasant whiffs, passed it in turn to the eldest daughter and son on down to the little younker that was hardly able to run alone.

After staying a few moments longer, I bade the family good night and went out with Haskell. I asked him if that was the way they lived, and he said it was, although they were a little on their good behaviour.

I asked H- where they all slept as I saw but one bed, and I thought by the looks there was no great chamber accommodations; he said they all slept in that one bed. I asked him where he slept and he said on the floor before the fire.

I asked why the old man did not cut his hair and trim his whiskers, for he wore them very long and, by the looks, never combed. He said the old man told him he never shaved, only when he got lousey.

I told Lyman I had a good deal rather he would be a safe guard there than myself, but he thought small favors should be thankfully received. And he did dislike the routine of camp life so much that he was willing to put up with a good deal. Biding him good night, I went back to camp well pleased with what I had seen and learned, and better satisfied to eat army rations then to sit at the table of a F.F.V.*

*NOTE: First Family of Virginia.

Corps Badges

Charles E. Davis, jr. writes:

It was while encamped at

Fletcher’s Chapel that we

received

the first order respecting corps badges, a description of which will be

seen by

the following circular:

Headquarters

Army of the Potomac,

March 21, 1863.

For the purpose of ready recognition of corps and divisions of the army, and to prevent injustice by reports of straggling and misconduct through mistakes to their organizations, the chief quartermaster will furnish, without delay, the following badges to be worn by the officers and enlisted men of all regiments of the various corps mentioned. They will be securely fastened upon the centre of the top of the cap. The inspecting officers will at all inspections see that these badges are worn as designated.

First Corps - a sphere: red for the First Division; white for the Second; blue for the Third.

Second Corps – a trefoil: red for the First Division; white for the Second; blue for the Third.

Third Corps – a lozenge: red for the First Division; white for the Second; blue for the Third.

Fifth Corps – a Maltese cross: red for the First Division; white for the Second; blue for the Third.

Sixth Corps – a cross: red for the First Division; white for the Second; blue for the Third. (Light Division, green.)

Eleventh Corps – a crescent: red for the First Division; white for the Second; blue for the Third.

Twelfth Corps – a star: red for the First Division; white for the Second; blue for the Third.

The sizes and colors will be according to pattern.

By command of Major-General Hooker,

S. Williams,

Acting

Adjutant-General.

On April 14, 1863, Sergeant John Andrew Boudwin recorded in his diary: "received our badge today it is a white piece of cotton the size of a half dollar and is worn on the top of our caps. It denotes 2nd Div 1st Corps de Armie."

Two letters of Charles Adams

In his matter of fact letters, Charles mentions 'Sally the dog,' the mascot of the 11th PA Vols., & the Balloon Corps of Professor Thaddius S. C. Lowe, also the post-war inventor of ice making machines & refrigeration. (I'll post more about both of them on the next web-page to be built. -B.F.)

Charles gained notoriety after the war for a series of poems he published in a faux-German dialect titled "Leedle Yawcawb Strauss." His playful nature and fondness for words is apparent in letters home to his siblings.Charles Adams to Sister Har-ner, 21 March, 1863; Charles Adams Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society. Used with permission.

Camp near Belle Plain March 21st / 63

Sister Har-ner

As it is

snowing today + I have a little more time than usual I thought I would

answer your letter of the 9th, though I am afraid I shall fall short of

materials in the shape of news. I received John’s letter last

night, also a Liberator with one Cousins “Patriotic Suggestion” in

it. We had a thunder storm here the 15th (Sunday) being the

1st of the season. Day before yesterday we had a division

review by Gen. Robinson who commands the Division + were to have

another yesterday by Hooker but the weather being stormy it was post

-poned. The boys got some paper collars of the sutler + wore

them out to the review + some of the Penn. regiment (feeling jealous I

suppose, they not having any) caught a dog + put a collar on

him + Let him run round among the troops which caused

P2

a good deal of sport. It has been snowing all the morning + has now turned to hail + probably will to rain soon. I am sitting on our bed writing this. Walter is beside me fixing his jacket, J.F. Pope [John Franklin Pope, pictured, right] reading the news paper + my other tent mates writing. We have got a pleasant fire in the fire place which keeps us quite comfortable nothing to do but to read + write + do just as we darn please. Some of the boys who are on guard to day have rather an unpleasant time but I am fortunate enough to be off to day. My bill of fare for breakfast this morning was toasted bread and butter, tea, soup + broiled salt fish which I bought of the sutler, not so bad as it might be is it? Our company is now the color company of the regiment + contains about 30 men. Perhaps you remember of my writing about visiting a plantation in January, while I was on picket. The pickets

P3

the other night saw somebody in the house (after all the lights had been put out + signaling to the ‘rebs’ across the river I don’t know what was done about it but I guess he was taken care of, as it is a high crime. I had a letter from Jane the other day she says that Mr T—g [?] is very sick with the liver complaint + is so thin + yellow that you would not know him. I saw a balloon the other day while on picket. I believe it was at Hooker’s Head Quarters taking observations of the rebel forces on the other side of the river. I had a letter from Walter Humphries last night he is in the hospital at Chestnut Hill Pa he says that a beautiful sword + sash was presented to the doctor of his ward + that he “had the honor conferred on him of making the presentation speech.” [Walter Humphries, pictured] I was surprised to hear that David Chapin was dead, and I guess the Bird st boys will

P4

feel lonesome, he always was round when there was anything going on about those parts. We have not heard anything more about going to Arlington Heights + I guess it was only a rummer. How does Dingy-Dongy get along. I wonder if she would know me now. I have had my hair cut once since I have been out here but not so close as it was when I left. I couldn’t stand the press to have it clipped again. ( If any of the Dorchester fellows are called for under the new Conscription act, Just tell them that they cant do better than to join the13th, as I believe they can join any 3 years reg. in the service + they cant find a better crowd of fellows if I do say it.)

Well I think I have done pretty well toward filling up the sheet so, as I shant “Wear + tear” my brain any longer I will “Storp the show.” Give my love to all the folks + Walters also (his request) + “pony up” with your letter as soon you conscience dictates

And oblige

Chawles

The enclosed trumpet was on my cap when I left Cameron, & I have kept it ever since. I thought I would send it home in a letter. I did not want to “cart” it round any more.

NOTES: Walter S. Fowler is his tent-mate, age 19 or 20, also a recruit as was Charles, Aug. 6, ’62.

J. Frank Pope l age, 18; born, Dorchester, Mass.; student; mustered in as priv., Co. A. July 24, ‘62 mustered out Aug. 1, 64; taken prisoner at Gettysburg, July 1, 63 and released, March, 64 residence, Milton, Mass.

(there is also a John Foster Pope from Dorchester but he mustered our March 7, ‘62 and went into the 1st Mass. H.A.)

Walter Humphries, another recruit of '62, almost made it through his service but sadly died just before the regiment left home. The roster states: age, 20; born, Dorchester, Mass.; farmer; mustered in as priv., Co. A, Aug. 7, '62; died of wounds received June 2, '64.

In the following letter Charles mentions a presentation sword the boys intended to purchase for popular Major Jacob Parker Gould. (In 1864, Gould earned his Colonel's commission and left the 13th to command his own regiment, the 59th Mass. Vols. Several men left with him to become officers in the 59th.) Although appreciative of the boys intentions, Major Gould declined the subscription and instead suggested the boys place the cash into a fund to help the wounded men of the regiment, where it would do more good. (More on that later.)

Charles Adams to Dear Sister, 27 February, 1863; Charles Adams Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society. Used with permission.

Camp near Belle Plain Va March 27th 1863

Dear Sister

Your

letter of the 22nd came to hand last night + suppose I may as well

answer it now as to keep putting it off. I was surprised to

hear that you were about to leave Berkeley St + I don’t know whether to

feel glad or sorry for the change, though I must say that it seems kind

of lone spun to think that [?] I suppose your principal

reason is for leaving now on account of having it so little room to

“rite” round where you are now. I suppose you will

look out for my things and see that they don’t get mussed up, You know

you can just lock them up as they are + I guess they will

hide well enough. My gun you can leave

where it is without George thinks he will want to use it –

also those books + things that I put in that old closet in my chamber

you can leave where they are. Hannah is willing. Of

course certain con-

P2

siderations tend to console me to my new home that is to be, so I think I can survive the shock. “We hear enough” about Manly Harden’s having charge of 800 niggers which would make 3 Regiments as large as ours is now , so he must be acting Colonel or Brig. General to have charge of them. I see that you are getting pretty well posted on my correspondences as father used to say. You have not got the name quite right, though it is near enough for “poor folks.” It happens to be Achsie instead of Achsah as you spell it, writes very interesting letters &c &c. So it seems Carol has turned up again. I meant to ask you if you had seen her lately. I should like to hear from her when she can use her hand so as to write. We are having reviews &c every few days + expect to have one in a few days by Joe Hooker. I don’t imagine we shall stay here much longer as there are any quantities of rumors about making reconnoissances &c &c

p3

The boys have started a subscription paper to present our Major (J.P. Gould) with a splendid sword, to be bought at Tiffany Bros N. York. We like the Major better than any other officer in the regiment. He used to be captain of a Stoneham company. The boys are in the habit of wearing paper collars when we go out to be reviewed + as I have not got a necktie I wish you would send some.

I believe I put ½ doz.[?] or more in a small round wooden box that figs came in, in my room Send me about 4 of them in a paper if you can find them. You spoke of that man that sung “Bow Wow Wow” in the Herald It did make me grin out loud to think of that Awful countenance John said that E--[?] Horn was at Harris Bros now. have you been to see him yet!

Just got in from a brigade drill of 2 hours + feel pretty well used up. I have just put my

P4

potatoes

on to boil + am going to have some boiled

meat +

mustard [?] with them. Walter is just cutting up some meat +

is going to make a soup. I don’t think of anything more to

write that will interest you. I should have written to John

today as I owe him a letter only I wanted to tell you about my Mine

potatoes. I will write to him next You perceive I

have written this time with a pen instead of a pencil. The

reason I have always used a pencil was because it was handiest, + I

thought all you wanted was to read them + let them quilt* – but

if you

would rather have me write with a pen I will do so.

Love to all short and tall. Write a letter the Sooner the

better, And do not fail, to send by mail, (As you

value your eyes) Those 4 neck ties

potatoes

on to boil + am going to have some boiled

meat +

mustard [?] with them. Walter is just cutting up some meat +

is going to make a soup. I don’t think of anything more to

write that will interest you. I should have written to John

today as I owe him a letter only I wanted to tell you about my Mine

potatoes. I will write to him next You perceive I

have written this time with a pen instead of a pencil. The

reason I have always used a pencil was because it was handiest, + I

thought all you wanted was to read them + let them quilt* – but

if you

would rather have me write with a pen I will do so.

Love to all short and tall. Write a letter the Sooner the

better, And do not fail, to send by mail, (As you

value your eyes) Those 4 neck ties

Your

Char-Char.

NOTES: *"let them quilt" - I believe I have transcribed this correctly although the photocopy is faint. If correct, perhaps George is making a pun, on the words 'quill' & 'quit.' It is difficult to know.

One of the other letters lists her address

as Berkeley St. care of Gen Fowler

The Bow wow wow song or Big Bow wow, is a song called 'Boston Harbor.'

It was very popular between the years 1860 and 1870.

The Chorus goes:

With a

big bow wow,

tow row row

Fal dee rall dee di do day.

I found the song on youtube: BOSTON HARBOR

A View From Headquarters, Army of the Potomac

General Hooker's Tent at Headquarters, Army of the Potomac, by A.R. Waud.

From mid-march to mid-April, Private Noyes was a clerk at Head-quarters Army of the Potomac. From this vantage point he observed a great deal about the operations of the Army of the Potomac, which suited the intrepid soldier well.Letter of John B. Noyes; By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Head

Quarters Army of the

Potomac

Officer of the Provost Marshal

General

March 30th 1863.

Dear Stephen

I believe I wrote you about 10 days ago. Since then affairs in the army have not much changed. We are a little nearer a forward movement however. Old documents useless in an active campaign have been packed up and sent to Acquia Creek. The different regiments in the service here have been ordered to march at a moments notice. Those soldiers destitute of Equipments and arms by reason of being recruits or convalescents have been furnished with arms. The orders regulating the number of tents to be allowed officers, and relating to baggage, and transportation have been issued. Men at the regiment point to unaccustomed supplies of hard bread at the Commissar’s, who however still issues bread daily to the Regiment.

Indeed everything looks to an early advance. Rains have been frequent lately, and the roads are quite muddy still, but frost is not out of the ground. To day a battery of 20 pounders a squadron of cavalry and a small body of infantry passed these headquarters going I know not where. The army is in excellent condition to move. The health of the army is excellent. Plenteous rations all winter with good accommodations, and not severe duties have put the army in good humor.

The army I need not say is large. How many regiments there are I Know, but such news would be contraband. Of the number in the various regiments fit for service I do not Know. But at the least I think Hooker has 100,000 veteran infantry soldiers, in addition to sufficient artillery and no mean force of cavalry. [Pictured, Major General Joseph Hooker].

Of the rebel force in and about Richmond I have no means of ascertaining the strength of their army, as they belong generally to regiments doing service near the banks of the river. The rebel regiments however are larger than ours. I have seen no deserter who gave the effective strength of his regiment at less than 500. In some cases old and tried regiments numbered 706. The ranks have been filled with conscripts. The whole south has been ransacked for conscripts this winter to fill up old regiments. We took a prisoner a few days ago who was on a visit home. He told us he didn’nt enlist but was taken out of his field while working. Another rebel a deserter was conscripted in Tennessee while on a visit to a cousin. He was allowed to choose his regiment and chose an Alabama one on the Rappahannock because he thought he should have a better chance of deserting here, where the armies are so near Each other. He had taken the oath of allegiance to our Gov’t. in Tennessee. A great many deserters come in now. More will doubtless come in when the weather is warmer & swimming the river becomes practicable. A Lieut. and his first three sergeants came over on a raft [last night/or] a day or two ago on Jeff. Davis’s fast day. One was a Canadian, one a Pennsylvanian, and a third a Massachusetts man by birth. They were in business South when the war broke out and did not wish to sacrifice their property there. Hence they were forced to enlist. They had been in service nearly two years. Several deserters came in to day. About rations they tell the same old story, - one pound of flour, & 4 oz. Bacon daily & a little salt & soda. No Coffee, Sugar, or Molasses except at rare intervals. The papers may have informed you that no furloughs are to be granted under the late orders after April 1st, another sign of active preparations.

Yesterday I went down

to the 13th Regt, 1st Corps distant about 6 miles. Men in

excellent condition. Great talk about the consolidation of

the

12th & 13th Reg’ts. This was news to me. I

don’t think

it will be advantageous. Our Regiment has too good a name to

loose. Fill up all the ranks with conscripts, if you please, but let

the old 13th with its memories still retain its identity.

Cedar

Mountain, Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburgh have proved the valor of

our men. It will not do to take away its number from the Massachusetts

Regt. in men & name. There is an espirit du Corps in

a

regiment like ours that it will not do for the Government to trample

upon. You haven’t sent me a novel lately, send one along.

Yesterday I went down

to the 13th Regt, 1st Corps distant about 6 miles. Men in

excellent condition. Great talk about the consolidation of

the

12th & 13th Reg’ts. This was news to me. I

don’t think

it will be advantageous. Our Regiment has too good a name to

loose. Fill up all the ranks with conscripts, if you please, but let

the old 13th with its memories still retain its identity.

Cedar

Mountain, Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburgh have proved the valor of

our men. It will not do to take away its number from the Massachusetts

Regt. in men & name. There is an espirit du Corps in

a

regiment like ours that it will not do for the Government to trample

upon. You haven’t sent me a novel lately, send one along.

I send with this letter a sesesh postage stamp for Mr. Butler whose stock I believe is small in sesesh stamps. If I can get a ten cent stamp I will send it along. Please present the stamp to our chum with my compliments. Hoping to hear from you soon both in book form and letter.

I am as ever

Your Aff. Bro.

John B. Noyes.

Shirks & Heroes

In the following narrative, Charles Davis describes a few recruits, less suited to a military life. Only clues to their identities, are given, and although 'Smoothbore,' is easily identified, 'Molasses,' is not. No one man has the record to prove conclusive ownership of that nickname; (and I spent a lot of time reviewing the rosters for a match). A good candidate for the placid hero who attached himself to the wagon train is in the roster; -- being the only soldier listed as 'attached to the division supply train, desertion removed.' I planned on revealing these identities, but perhaps because of the sensitive nature of the material and the chance for error, its best to leave them un-named.The description of 'bummer' Bob Armstrong, was omitted from this narrative. The article about 'Bob', "A Narrow Escape," appears on another page of this website. I hope you enjoy Davis's humorous character sketches. - Brad Forbush.

"From Three Years in the Army;" by Charles E. Davis, Jr., Boston, Estes & Lauriat; 1894. (p. 176-183)

We had work enough during the day, chopping wood, policing camp, guard duty, etc., to keep us from despising our leisure. Our evenings were spent in reading or playing cards, or, as it often happened, in dropping into each others’ huts for a chat or to hear the latest news. Newspapers were exchanged and their contents discussed. The published letters from correspondents were always read with interest, particularly those which related to our own corps.

The qualifications of general officers, and plans of battles, were also freely discussed. Songs were sung and gossip repeated. At some of these camp-fires curiosity would often be expressed to know what had become of those shirks and bummers who believed with the Holy Writ that “a living dog is better than a dead lion.” We had, like other regiments, some curious specimens of this genus, and our narrative would be incomplete without relating something about these patriots.

Shirks

There was one in particular

whose blundering ways, when

recalled, afforded a good deal of amusement. He was about as

much of a soldier as a hen, and his careless, bungling habits caused a

good deal of friction in the daily life of some of us. No

soldier likes to have his calves used as a door-mat for the feet of the

man behind him. The champion of all offenders in this respect

was a man who was called by the sweet name “Molasses.”  He was

thrust upon us the day before we left Fort Independence. No

one knew him before he joined the regiment, and only one man sought his

acquaintance afterward. He was homely in appearance,

unshapely in form,

awkward in gait, and as ignorant and dirty a slouch as could be

found. His gait was like that of a man who, having spent his

life in a ploughed field, could not divest his mind of the idea that he

was still stepping over furrows. He was about fifteen years

older than

the rest of us, and his manly breast was undisturbed by a single thrill

of patriotism; each corpuscle of blood, as it flowed from his heart,

carried to the remotest extremity of his body one desire, - “Put money

in thy purse.” His mercenary and penurious spirit prompted

him to increase his income by the sale of small wares to his comrades,

who despised him for his unsoldier-like thrift. He was

generally absent when his services were needed, so that the

man whose name was next on the list had to take his place, which always

happened when the duty was unusually hard or dangerous, as occasionally

happened at the end of a long march. With all these

failing he had, to a remarkable degree, the God-given instinct which is

said to be one of the qualities of the war-horse, - he could snuff the

battle from afar, and took advantage of this gift by absenting himself

at a time when it was difficult, afterward, to say absolutely whether

it was cowardice or his wandering spirit that prompted him to “light

out,” as could have been determined if he had waited until the last

moment. Just before we went into the battle of Manassas,

having been too closely watched to enable him to disappear, he stopped

to tie his shoe, and never returned to the regiment again.

When we were small boys and saw the troops in fine uniforms marching

through the streets, it seemed a glorious thing to be a

soldier. In our youthful imagination every man who carried a

gun was a hero, but after having one’s heels trod on and the calves of

one’s legs kicked by the muddy feet of a man who had no rhythm in his

soul, there didn’t seem to be quite so much of a heroic halo

surrounding the soldier as we had pictured. Therefore we were

glad he never came back.

He was

thrust upon us the day before we left Fort Independence. No

one knew him before he joined the regiment, and only one man sought his

acquaintance afterward. He was homely in appearance,

unshapely in form,

awkward in gait, and as ignorant and dirty a slouch as could be

found. His gait was like that of a man who, having spent his

life in a ploughed field, could not divest his mind of the idea that he

was still stepping over furrows. He was about fifteen years

older than

the rest of us, and his manly breast was undisturbed by a single thrill

of patriotism; each corpuscle of blood, as it flowed from his heart,

carried to the remotest extremity of his body one desire, - “Put money

in thy purse.” His mercenary and penurious spirit prompted

him to increase his income by the sale of small wares to his comrades,

who despised him for his unsoldier-like thrift. He was

generally absent when his services were needed, so that the

man whose name was next on the list had to take his place, which always

happened when the duty was unusually hard or dangerous, as occasionally

happened at the end of a long march. With all these

failing he had, to a remarkable degree, the God-given instinct which is

said to be one of the qualities of the war-horse, - he could snuff the

battle from afar, and took advantage of this gift by absenting himself

at a time when it was difficult, afterward, to say absolutely whether

it was cowardice or his wandering spirit that prompted him to “light

out,” as could have been determined if he had waited until the last

moment. Just before we went into the battle of Manassas,

having been too closely watched to enable him to disappear, he stopped

to tie his shoe, and never returned to the regiment again.

When we were small boys and saw the troops in fine uniforms marching

through the streets, it seemed a glorious thing to be a

soldier. In our youthful imagination every man who carried a

gun was a hero, but after having one’s heels trod on and the calves of

one’s legs kicked by the muddy feet of a man who had no rhythm in his

soul, there didn’t seem to be quite so much of a heroic halo

surrounding the soldier as we had pictured. Therefore we were

glad he never came back.

Another specimen we had was “Smoothbore.” If there was a man in the regiment who had fewer instincts of cleanliness than this man he will lose the opportunity of being recorded in these pages. Smoothbore acquired his sobriquet from that antiquated and useless arm called the smooth-bore musket. The likeness of the two, so far as usefulness went, was such that the name stuck to our hero. He was bitterly opposed to the use of water in any way but internally. The men of his company, with the authority of the captain, once undertook to wash him, and it required a considerable force to carry out this laudable purpose. When his clothes were removed he was found to be as dirty and lousy as a saint under penance. Having succeeded in getting him into the brook, they procured some flat stones and scrubbed him until he looked like a boiled lobtser. In consequence of his struggling, - so the boys explained to the captain in answer to Smoothbore’s complaint of hard usage, - some of his hide, that was too thing to stand the chafing, came off with the dirt. It was a useless piece of work they did, for the experience intensified his prejudice against the use of water, which he never after used externally. Just before the battle of Manassas he deserted, carrying with him an inexhaustible supply of the pediclus vestimenti. He was so melancholy and selfish that we were glad he also had departed.

We had great pleasure in recalling these old heroes, who had escaped death so many times by keeping out of danger.

The “shirk” whose history we are about to relate did not

desert. He neither “struck for the flag” nor “struck for

home.” He stayed with us for three years, because it required

more energy than he possessed to desert, and because he led a peaceful

and contented life in spite of his being in the army. He was

one of those taken into the regiment to fill up the quota of a company

as we were about leaving home. Though an enlisted man he

never did any duty as such, preferring the primrose paths of a pampered

menial where there was plenty to eat and little to do. He

must have had a good deal of shrewdness to have succeeded for three

years in escaping the duties for which he enlisted. He could

whine to perfection, and very early in his service he acquired a

reputation for being absolutely worthless for any duty requiring

courage or exertion – the position of hostler filling his

ambition. At one time, being out of a job as hostler, he

sought admission to the hospital; but the doctors would not have him

occupying a bed, nor would they employ him in any capacity, sending him

back to his company. He was useless in his company, as he was

elsewhere, so he was turned out and told to “go to the devil; go

anywhere: but you can’t stay with us.” He became attached to

the wagon-train, where he spend the rest of his service, doing as

little as possible.

The “shirk” whose history we are about to relate did not

desert. He neither “struck for the flag” nor “struck for

home.” He stayed with us for three years, because it required

more energy than he possessed to desert, and because he led a peaceful

and contented life in spite of his being in the army. He was

one of those taken into the regiment to fill up the quota of a company

as we were about leaving home. Though an enlisted man he

never did any duty as such, preferring the primrose paths of a pampered

menial where there was plenty to eat and little to do. He

must have had a good deal of shrewdness to have succeeded for three

years in escaping the duties for which he enlisted. He could

whine to perfection, and very early in his service he acquired a

reputation for being absolutely worthless for any duty requiring

courage or exertion – the position of hostler filling his

ambition. At one time, being out of a job as hostler, he

sought admission to the hospital; but the doctors would not have him

occupying a bed, nor would they employ him in any capacity, sending him

back to his company. He was useless in his company, as he was

elsewhere, so he was turned out and told to “go to the devil; go

anywhere: but you can’t stay with us.” He became attached to

the wagon-train, where he spend the rest of his service, doing as

little as possible.

Soon after the regiment was discharged, concluding that he was unfitted for the active duties of a man who had to earn his living by the sweat of his brow, he entered that haven of rest called the almshouse. This step was not taken, however, until he had thoroughly tested the capacity of his friends in supporting him.

He had superior qualifications for a pauper’s life, - contentment, perfect health, a good appetite, and excellent digestive organs, Un-fortunately for him his appetite was a little too good, as it excited the animosity of the cook, and through her the selectmen of the town.

It often happens in country towns, when the question of reducing the taxes is agitated, that the selectmen call round to the almshouse to see if the butcher’s bills cannot be trimmed down a little, for, as Ben Franklin said, “A penny saved is a penny earned.” Now, when thy learned what an appetite our old hero had, and listened to the grumbling of the cook, they determined to bounce him out of his comfortable nest; but to turn an old soldier out into the cold world meant something in a community where every soldier was a hero. The selectmen knew the women would have made it hot for them if they tried it. So they reflected; and in a quiet way they began to question him about his past life, and in what towns he had paid taxes, until they discovered a flaw in his settlement in the fact that his enlistment was credited to another town. They could hardly repress their fiendish glee at this discovery, and promptly notified the other town of the fact, with the request that they must provide for him. Then followed a long dispute, which ended, at last, by his removal. The authorities of the town to which he was removed were dismayed at the prospect of supporting him in idleness for long years to come, and would have rebelled but for the sentiment which the women of this town kept alive for the old soldier, as they do in other towns in the State, without regard to his worth as such.

After the matter was finally settled the question arose as to whether or not some income might be obtained toward his support; whereupon the authorities paid his expenses to Boston to hunt up some of his old comrades to see if they couldn’t aid him in procuring a pension, and this is how our interest in him was renewed. We were much interested when he informed us of the purpose of his visit; but a disability must be found before papers could be made out. This was a difficult thing to do, as his three years of service had been passed in continuous tranquility, remote from danger. He was asked to mention some accident or sickness that by a possible stretch of the imagination might be construed as having affected him. When asked if he ever had any pains he said, “A year or two ago I had a pain in my back.” – “What do you think was the cause of that ?” we inquired. This was a poser. Though he couldn’t look into the future, he still held his grip on the past; so he slowly carried his mind back twenty-four years to a day when riding on the ammunition wagon, he recalled that it suddenly stopped, throwing him forward with his hands resting on the haunches of the mule in front of him, from which position he allowed that he pushes himself back into his seat without difficulty. He felt nothing at the time, nor, indeed, until twenty-two years had passed. What an ideal life this man must have led, that it was necessary to go back twenty-two years to find cause for a passing pain in the back! We looked at this hero, as his mind went back to the stirring scenes of the war, and noticed how gently time had dealt with him. His fat round body and rosy cheeks showed the value of regular habits, with plenty of food and sleep, and nothing to do. It was hard lines for us to do it, but we broke it to him as gently as possible by telling him that, instead of the government owing him anything, he owed the government a pension. He then left us and returned to the alms-house. The case didn’t end here, for a committee of the selectmen came to Boston at the town’s expense, to interview members of his regiment and to urge his claim, saying it was the duty of his old comrades to assist in obtaining a pension, which would help the town in its support of him. These worthy men, after listening to our refusal, and our statement that he was a disgrace to the regiment, had the effrontery to say it was our duty to support him, and lectured us on our lack of feeling for an old comrade-in-arms, adding that they should always remember what a contemptible set of men composed the Thirteenth Regiment.

As long as there are women in that town, we needn’t worry about his support, for they will look after this old hero, and shower upon him all the blessings their tender sympathies can suggest.

After we have all joined “the innumerable caravan” that Mr. Bryant wrote about, he will still be living – probably the last surviving member of his regiment. By that time the women of his town will cry, “For shame! to keep an old scarred veteran in the almshouse!” They will possibly hold an annual “fair” to provide money for his maintenance in some respectable family where he can have comfort and liberty. On festive occasions he will be trotted out as the brave soldier who made great sacrifices that the country might be saved. On Memorial day he will be carted round in a carriage, and the orator will point to him with feelings of pride as “a glorious old relic, whose deeds of valor in the War of the Rebellion shed a luster on the town,” and the crowed will respond with long-continued applause. When he is ninety year of age, perhaps some giddy young woman, burning with desire to be a soldier’s bride, will marry him, and in the year two thousand and something she may be drawing a widow’s pension for services her husband was supposed to have rendered in the nineteenth century. Stranger things than these have happened.

In a regiment of men you will meet all shades of character. The generous and the frugal, the obliging and the surly, the conscientious and the unscrupulous, the brutal and the gentle, the cheerful and the dejected, are all bunched together in closest intimacy. Some may be found full of merriment, overcoming trials and privations with abundance of good-nature, while others are so despondent that nothing ever seems right. Men are to be found who are always ready to do a kind action, and others who will impose on the good-natured to the utmost limit. The varnish of politeness and affability which one acquires by mingling with society soon disappears from a man who takes his place in the rank and file of an army. So long as he does his duty he may be as disagreeable as he pleases, without violating an army regulation. Education and bringing up may assist in concealing one’s natural instincts for a while, but in the end a soldier stands with his comrades for just what he is. If a man’s inclination is to bully, it will show itself in a thousand ways; if lazy, at the first call of duty; if he lacks courage he will endeavor to shirk the first danger that threatens. You see human nature just as it exists where men are unrestrained by any civilizing influence.Heroes

Some of our young readers –

supposing of course, that we have

young readers – may wonder why we do not say something about the heroes

of the regiment. The fact is that brave men, men who only

needed an opportunity to distinguish themselves, were as plenty as

huckleberries. It is not the men whose names appear

the

oftenest in the newspapers that are the greatest heroes or the most

courageous men. In truth, every soldier knows that some

pretty poor specimens have acquired renown by pushing them selves

forward in the daily press. When a boy, sitting beside us at