Why Does a Private Soldier Have So Much More Sense Than A General?

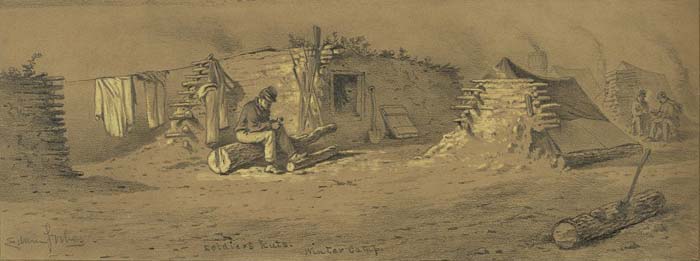

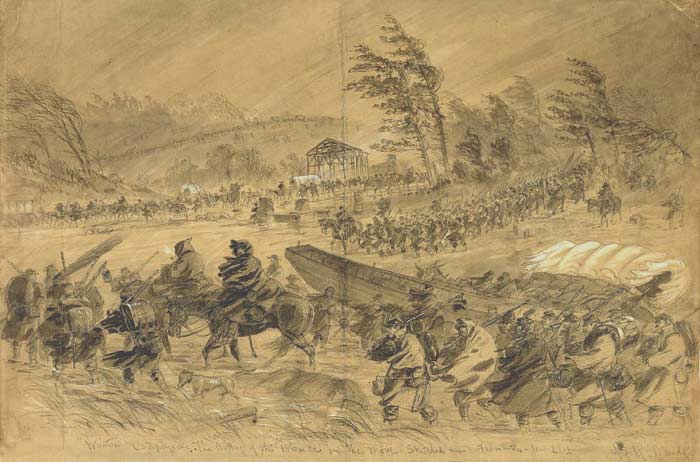

Winter Camp, January - March, 1863

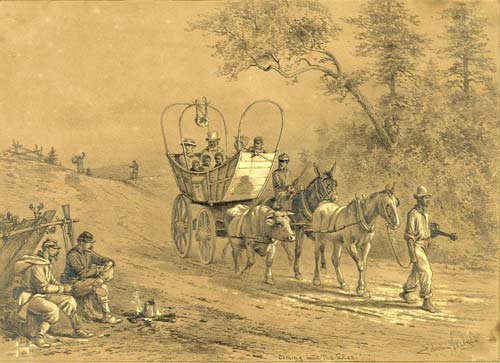

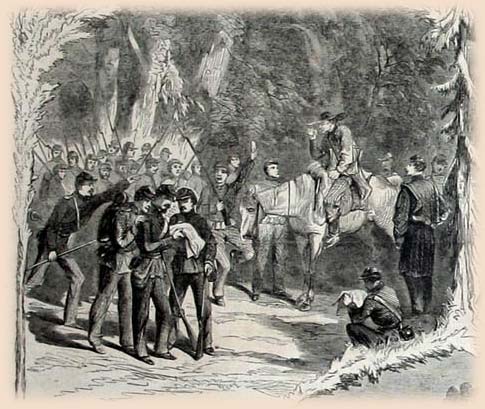

Detail from Winslow Homer's painting, "Rainy Day in Camp."

Introduction: What's On These Pages

This section is divided into 3 pages, one for each month of winter camp, January, February & March, 1863 respectively. Interspersed are 2 stand alone humorous articles. "Grins," authored by Clarence Bell of Co. D, recalls times in the army that made the soldier smile. "Shirks," by Charles E. Davis, jr. provides character sketches of some of the less-soldierly members of the '13th Mass.' Narratives of camp life & military matters are also sprinkled throughout the pages. [To navigate to the 2nd and 3rd pages, click on the menu tab in the side bar, or, at the end of this page, click 'next page' to go to page 2.]

In January letters and reminiscences of George Hill, Co. B; Dennis G. Walker,Co. A, discuss morale in the army following the disastrous campaign of Fredericksburg. (Walker was a great soldier but a lousy speller.) These letters are followed by an account of Burnside's 2nd failed campaign, the infamous 'Mud March.' Commentary is given by Charles E. Davis, Jr., D.G. Walker, Sam Webster & Charles Leland. The long reminiscence 'Grins,' follows.

In February, [page 2] recently promoted officers are outlined. Charles Leland relays news from camp, and brings up the topic of army desertions. A brief essay follows examining patterns of desertion during the history of the '13th Mass.' Then, Charles Adams, of Company A, mourns the loss of a comrade who died of disease at Aquia Creek Landing. Private John B. Noyes, wounded in the leg at Antietam, returns to camp at this time, and brings us along on his shift, as he does picket duty, in the snow. Several contemporary (1863) images of Washington, D.C. follow, with commentary by Noyes. Warren Freeman, who was hospitalized near Aquia, also returns to camp at this time. Lame from hard marches, invalid Freeman suffered untold agony lying on the ground, unsheltered in frigid weather, during the battle of Fredericksburg.

In March, [page 3] George Hill received a box from home and details all the goodies packed inside. Private Noyes takes us on a long muddy trek through the camps of the Army of the Potomac over to Head-quarters. Sam Webster and Austin Stearns describe 'some of the locals.' Stearns gives a vivid description of one of the local families when he visits his friend Lyman Haskell on 'Safe Guard' duty. Charles Adams banters with his siblings back home in Boston about his tent-mates, officers, army reviews, picket duty, food, the weather and other matters. His 'laissez-faire' tone relegates military affairs to the background. At the end of the month, private Noyes, now a clerk at head-quarters, reports on the condition of the Army of the Potomac from a broader perspective, as it prepares to open the coming Spring Campaign.

The exposition 'Shirks & Heroes' by Charles E. Davis, jr. ends the section.

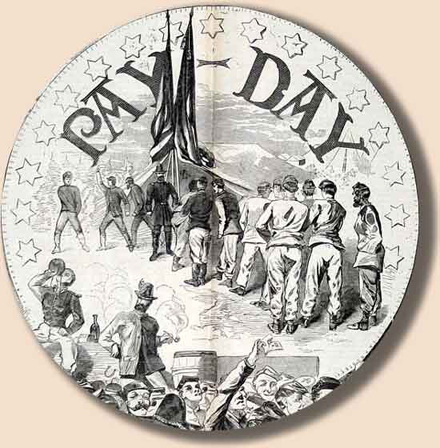

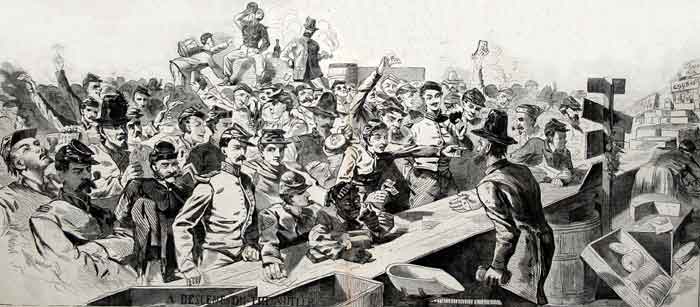

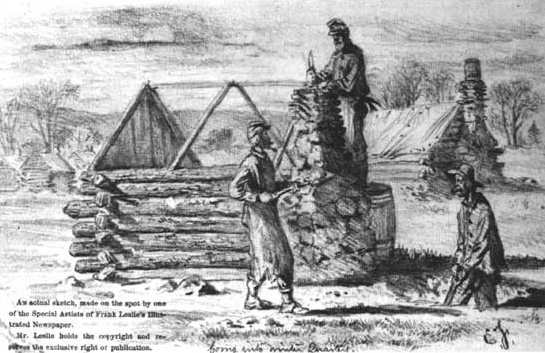

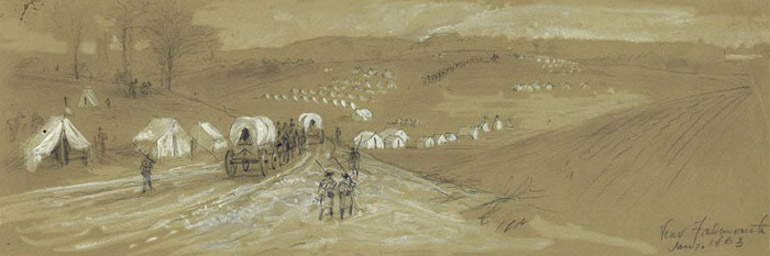

PICTURE CREDITS: All images are from the Library of Congress digital images collection, with the following exceptions: John S. Fay courtesy of Mr. Peter Bolan; The Devil sketch, & happy pigs sketch, by Albert Hurter; from his book "He Drew As He Pleased" accessed via the Internet. Photos of Dennis G. Walker, & Sam Webster, are from Mr. Tim Sewell who shared these images from his ancestor James Lowell's scrapbook; The "Tent," by Austin C. Stearns is from his memoirs, "Three Years with Company K," edited by Arthur Kent, AUP Press, 1976; "Payday in the Army of the Potomac" by Winslow Homer, The Fredericksburg Cartoon, & "Distributing the Mail" are from Sonofthesouth.com (Harper's Weekly); The Charles Reed sketches were accessed digitally from the Book HARDTACK & COFFEE, by John D. Billings; "Tipping the Chimney" by Charles Reed, resides in the Lib. of Congress but was accessed via American Heritage Picture History of the Civil War, Doubleday & Co., 1960; Bugs were drawn by illustrater Oliver Herford; Robert E. Lee, is by Jack Davis; Most of the drawings were done by Civil War Correspondent Edwin Forbes. ALL IMAGES have been edited in photoshop.

WINTER CAMP

From Three Years in the Army; by Charles E. Davis, Jr., Boston, Estes & Lauriat; 1894.

New Year’s day brought

forcibly to mind that our service of

three years was about half completed, though the remaining eighteen

months

seemed a long look ahead. The regiment

had been reduced from 1,038 to less than 350 men, the number now

mustered at

roll-call. Nearly all of this reduction

had occurred during the last five months.

Counted in with this reduction were the men who were detailed at

brigade, division, corps, headquarters, performing services for which

they had

some special qualification, while a considerable number of the rank and

file

had received commissions as officers in other regiments.

Officers’ luggage had been so reduced that

the distinction in rank was much less marked than during the early part

of our

service. Instead of one hundred men,

some of the companies had only twenty to twenty-five. The officers of a

company

were little better off than the men, and as time wore on the difference

became

still less, while the hardships and privations increased, as will be

seen

farther along.

Having made our huts as

comfortable as possible, we settled

down for the winter, glad enough at the prospect of a respite, as we

fondly

imagined, from marching and fighting.

Some of the boys had taken great pains in the construction of their

huts, particularly in building fireplaces and other conveniences for

their

comfort and pleasure.

As long as the sutler remained

with us, and our credit

continued, we managed to live luxuriously, as compared with our

experience of

the last four months. We could always

procure sugar and lemons from the sutler, to which we added water; and

when our

efforts were successful, a little stimulant, for the “stomach’s sake.”

As long as the sutler remained

with us, and our credit

continued, we managed to live luxuriously, as compared with our

experience of

the last four months. We could always

procure sugar and lemons from the sutler, to which we added water; and

when our

efforts were successful, a little stimulant, for the “stomach’s sake.”

Just as soon as we became

comfortably settled in winter

quarters we found it necessary to devote our surplus energy to hunting

that sample of the Divine workmanship scientifically known as the

“Pediculus humanus.” His is a wonderful little chap,

satisfied to live in Stygian darkness, hiding himself and all his

family from the closest scrutiny. After an hour or two of the

most careful examination you replace your shirt satisfied that you have

removed the last one, and inwardly gratified at you success, when, as

if reading your very thoughts, he gives notice of your failure, and off

goes your shirt again for another hunt. Away go all your New

Year’s resolutions.  At last you come to realize

that all your

persistent efforts of cleanliness and watching will not ensure your

continuous freedom from this disgusting little parasite.

At last you come to realize

that all your

persistent efforts of cleanliness and watching will not ensure your

continuous freedom from this disgusting little parasite.

There was another bloodthirsty little wretch that bothered us a good deal in summer, and that was the “tick.” Of course we had fleas, as might be expected when living in a tent no bigger than a dog-kennel, but the tick was a real enemy that did business on business principles. If you caught him in the act and brushed him away, as you supposed, he simply dropped his body, as one would a knapsack and with his head firmly imbedded under you hide, would continue to increase and multiply, as the Bible requests mankind to do, until very soon you would become tortured with a most disagreeable irritation, often likely to become very serious and occasionally resulting in lameness for weeks. What with lice, ticks, centipedes, earwigs, etc. there was food for reflecting how

“God moves in a mysterious

way

His wonders to perform.”

In spite of all these drawbacks we did get some pleasure out of life.

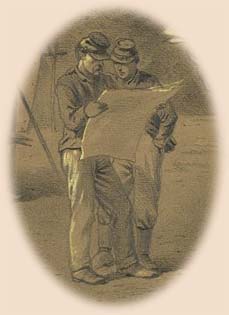

By aid of the newspapers we kept as well-informed as the rest of the world, while letters and papers from home supplied fresh material to be repeated at some other fireside than our own.

We all had our ideas of running a campaign, and freely criticized the plans of our commanders, wondering why a private soldier had so much more sense than a general.

Of course we were

busy every day with drills, guard duty, fetching our supply of wood,

which had

to be hauled two or three miles, and the building of

corduroy roads, so

that when evening came we were glad to fill our pipes and stroll into

other

quarters until tattoo, when we answered to our names and then turned in

for the

night, hoping no “long roll” would turn us out before

morning.

into

other

quarters until tattoo, when we answered to our names and then turned in

for the

night, hoping no “long roll” would turn us out before

morning.

In building huts for winter quarters, opportunity was afforded for the exercise of such ingenuity or fancy as the boys possessed. Some were satisfied with the simplest arrangement that could be made, while others spent time and labor to perfect a habitation that in comparison to some others suggested the luxurious. As in each case the roof was the shelter tent, there was some uniformity in appearance, the size of the roof indicating the number of occupants. Some dug into the ground for space, and others into the air. Some were two stories in height, and few were dug into the hill-side. All pretty nearly represented the degree of comfort the occupants desired. Each was provided with a chimney made of barrels or boxes, according to circumstances.

For amusement, advertisements were inserted in some of the Northern papers, asking for correspondence with some young lady of matrimonial inclinations; to which the first mail brought about a peck of answers that were distributed among the boys. The same thing was done the previous winter while were encamped at Williamsport. At that time answers came by the bushel. It was astonishing how many young women were so inclined. We got a good deal of fun out of this, which offset the disappointment that was experienced in “poker.”

JANUARY, 1863;

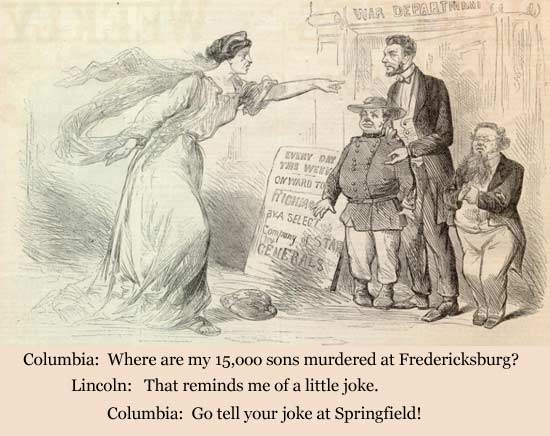

Strife at Headquarters

The disaster at Fredericksburg did not prevent General A. E. Burnside from shirking his responsibility for command of the army. He made new plans to cross the Rappahannock River and attack General Lee's Army. But many of Burnside's high ranking subordinate Generals had lost faith in his ability to command. Two of them visited President Lincoln, December 30th, and cautiously expressed the fact that the army was dispirited, Burnside's new plan could end in disaster.1 An already depressed Lincoln told Burnside not to make a move without letting him know. Burnside's plan was scrapped.

On January 1st, 1863, President Lincoln signed into law the controversial Emancipation Proclamation. "No slaves were freed specifically at that moment, for the Proclamation pertained only to areas "the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States." These areas were indicated. However, as Federal armies advanced into these areas, the slaves were to be free. Further, this final Proclamation provided that former slaves would be officially received into the armed services of the nation." 2On January 7th President Lincoln endorsed General Burnside's new plan to cross the Rappahannock and attack Lee.

The day the move began, January 19th, Burnside got into a heated argument with two of his high commanders, Maj-General William B. Franklin and Maj-General William F. Smith. Franklin & Smith said the troops were demoralized and the plan would fail.3 The men in the ranks were aware of the discord and lack of faith in Burnside expressed by the high command..

The weather was good until January 20th when it started to rain. The rain didn't let up and Burnside's army was stopped fast in the mud. He was defeated by the weather. The drenched muddy army slogged back into camp January 24th.

Angry and exasperated, General Burnside traveled to Washington to meet with the President. Burnside had drafted orders to remove his enemies, (a McClellan faction) from the army. He wanted Hooker removed for insubordination, General McClellan's friends Franklin & Smith relieved of command, along with General Ferraro &, General Sturgis. Generals Newton and Cochrane who met with Lincoln in December would be sacked along with division commander William T. H. Brooks. He also offered to resign his commission, saying he never wanted the command in the first place.4

Lincoln accepted Burnside's resignation and appointed Maj-General Joe Hooker to command the Army of the Potomac. Lincoln also relieved Sumner (due to age) and Franklin from command. Burnside was given a 36 day furlough. He accepted the decision with magnamity. 5

NOTES

1. Fredericksburg!

Fredericksburg!; George C. Rable, p. 391.

2. The Civil War Day by

Day, E.B.

Long with Barbara Long, 1971, Doubleday &

Co., re-printed by Da

Capo Press. p. 306.

3. Rable, p. 411.

4. Long & Long, p. 315; Rable p. 421-422.

5. Long &

Long, p 315; Rable, p. 422.

MORALE - Letters of G.H. Hill & D.G. Walker

Camp

near Bell Plains Virginia

Tuesday

Jan 6th

1862

Dear Aunt Fanny

Were you in my place and I in yours, I know you would think hard of me if I, with nothing particular to do and plenty of time to do it, could not devote a few moments to the answering of your letters which you had hastened to write, amid all the inconveniences of camp life, lest I should feel an unnecessary anxiety on your account. Reverse the terms and you have my feelings. I wrote you the day we crossed from the opposite side of the Rappahannock which was Dec 16th and have not received an answer. 21 days is a long time to wait to hear from one we love, particularly in the Army. You forget that my letters are the bright spots in my present life, and those I receive from you are among the brightest. Now if I had some nice “sweet – heart” to write me nice long love letters it would not be so bad but in the absence of that I must hear oftener from Aunt Fanny.

I will write to her again and perhaps this time she will be more prompt. She is a dear good Aunty but she don’t seem to think that her nephew in the Army is waiting anxiously and

P2

watching every mail to hear from her.

We are receiving news from the West which we hope will be confirmed. Rosecrans is a good General and we anticipate much from him.

I am entirly [sic] recovered from the effects of our “Scirmish” both Morally and physically. [sic] I was a little discouraged at first but I am not now at all. We must succeed. The Presidents Proclamation has reassured me much. I think it betokens more energetic action for the future.

Q: why are not the

people unanimous in support of the Administration, I tell you

this party wrangling at home

discourages the Army more than defeat in the field. Besides

it encourages the enemy to greater

exhertions [sic] and thereby ensures to us harder work in subduing

them.

If the Northern people were with us heart

and hand we would subdue the Rebels in six months but alas they are not

and we must

struggle on as best we can. I do not

fear our enimies [sic] in front one half so much as I fear those

sneaking,

mealy mouthed, would-be-secessionists who are gradually undermining our

government by their opposition to the Administration.

Q: why are not the

people unanimous in support of the Administration, I tell you

this party wrangling at home

discourages the Army more than defeat in the field. Besides

it encourages the enemy to greater

exhertions [sic] and thereby ensures to us harder work in subduing

them.

If the Northern people were with us heart

and hand we would subdue the Rebels in six months but alas they are not

and we must

struggle on as best we can. I do not

fear our enimies [sic] in front one half so much as I fear those

sneaking,

mealy mouthed, would-be-secessionists who are gradually undermining our

government by their opposition to the Administration.

Wednesday Evening.

At last I have a letter. I at first thought I would begin anew but I concluded that a little scolding would not hurt so shall “go ahead”

P3

Bless your dear soul, we do have “dead loads” of new clothes but “wars de machine” ? Think you we have all the improvements of modern times with us way out here one hundred and two and a half miles from civilization. Nary a prove”

When we get to Richmond, then I will try and get my photograph as you wish, only don’t you think it would look out of place to have my rifle in my hand and “my cap off”?

Yes I received your letter containing the outrageous & unjust slanders on McClellan.

P4

We are now fixed quite comfortable. We have built us nice log houses our tents serving for roof and we have a fire place in it and are as happy as you please. How long we shall stay to enjoy them of course we can not tell. I wrote to Adda last week. I am glad to hear of Mr Cutter’s recovery. Remember me to him and also to Mrs. Cutter. I wrote to Mrs Woods the lady I boarded with about the Gas fixture but she says she never saw it. Either she “fibs” or else some one who occupied my room after I left got it. When did Carrie Beck go to Richmond ?

Write soon and accept with much love from

Your affc nephew

Geo H.

(Direct as usual)

Letter

of Dennis G. Walker - Company A

Letter

of Dennis G. Walker - Company A

Dennis G. Walker of Company A, (pictured) was a great letter writer, but not much of a speller. In fact, he almost needs a translator, but I decided to leave his spelling in tact. Walker's descendant, David Walker, did the digital transcriptions and shared several of Dennis's war time letters and letter fragments with me.

This letter fragment is undated, but it speaks strongly of the morale of the Army of the Potomac. I think it was written after the Army's defeat at Fredericksburg, between December 17, 1862, and January 20th 1863. This is because of his statement, "I no that this war might of Ben setled long Be fore this and it would of Ben if ower Gen hed Ben let a lone." This refers to the sacking of General McClellan by President Lincoln in November, 1862. There is no mention of General Hooker, who replaced Burnside immediately following the 'Mud March,' January 26, 1863. (The appointment of Hooker immediately boosted the morale of the troops.) There is another letter of Walker's dated January 25th regarding Burnside's 'Mud March' below.

yo say that this war looks very dark to yo. it dose to me som times although I do not dwell much on it noing it can not always last. I hav Ben throu consiterble and fear as much But my mind is not altered yet I feal as willing to fight for my country as ever I did.

I hav felt som what discouraged be-fore not to se the slow progress that we ar making and the many trators in ower mist working a gainst ous. I no that this war might of Ben setled long Be fore this and it would of Ben if ower Gen hed Ben let a lone. But now it is far from bein setled and things ar coming to a Point we must do somthing shortly or all is lost. hed we aught to set down in dispair and se ower country lost for ever and trampled on by traitors.

I hav often thought and wished that the South could gain thair independence and if things ar a goin on the same as thay hav Ben thay will get it and that soon to and when I think of it I feal in hopes that thay will get it. But thair is a nother light to look at this thing in.

if the south should gain thair indpendance would this thing Be setled I think not the South would hav meanes to fight with and in a few years the Niger would kick up a nother smell and a nother war would Be on foot and a Bluddier war then this ever was and then we could not whip the South and the result would Be a king to Governer ous. it is of no yous to talk of southern confederacy that is not a goin to setle this thing + this is one of the Best Goverments that ever was in existence and ar we to look on and se a fiew traitors distroy it.

this is hard to think of

after ower fore

farthers

fought so hard for it, and then we should let it go with out a strugle.

hav the

people not yet waked up or ar thay faint.

this is hard to think of

after ower fore

farthers

fought so hard for it, and then we should let it go with out a strugle.

hav the

people not yet waked up or ar thay faint.

I am not sory that I came to war and I hope that I chal se this Rebelion Pute down Be fore I ever return. I was not hired to com to war but vollenteared to com and fight for the old flag. I hav sean fight and I exspect to se more. thair is a plenty of men in the New England States that ar no better then I am to face the enemey then I am. if thay ar thay ar just the men that we want.

thay can stay at home and cry out why dont the army move why dont thay com out hear and move it. we can whip the South easey if we hav a mind to do so and we chal never se peace until we do. The presidant has fool power to call for all the troop he likes and I hope he will call for eighteen 18 hundred thousan and send them in to the field as fast as he can cloth and quip them and then Just whipe this Rebelion out. this is the way to hav peace and the onley way the south come to a conscription long time a go and took evry man that was able to bair armes. I would like to se the 9th months men mustered out and subject them to a draft…

Digital transcription by David Walker.

Life in Camp

The Following is from "Three Years with Company K" ; Sgt. Austin C. Stearns, Deceased, Edited by Arthur Kent; 1976 Fairleigh-Dickenson Press; (p. 149 - 150) Used with permission.

Seeing or hearing no signs of moving, the boys began to fix up their quarters, every one to suit himself. Dan Warren and myself pitched together, and after a little we commenced to improve our tent. We dug out the earth the bigness of the tent, about a foot and a half deep, and getting some poles, we locked their ends together and placed them around to keep back the earth, banking up on the outside. In the inside we drove down some crotched sticks and placed some cross pieces, and, in turn, on these placed some long, slim, smooth poles covering about two thirds of our room. In daytime this served as a seat, and at night we slept soundly on this our spring bed.

In the corner

next to our

head we built a fireplace, the

chimney on the outside of sticks laid up cobhouse fashion and plastered

with

mud. The door of

the tent was on the

same side with the chimney; under the bed we kept our store of wood,

while our equipments

were stored wherever there was room.

Here we were snug, and tight, and warm, and done our

cooking, ate, and

slept the greater portion of our time away.

Not all the boys of the company were so comfortably housed

as we

were. We lived

quite an easy life,

drilling when the weather permitted, and doing picket duty in all

weather.

I was out on picket the first day of January 1863, when early in the morning there came in a load of contrabands; they had a yoke of oxen hitched to a cart on which was all their worldly possessions; they were of all ages, from the helpless babe to the old grey heads; they were all smiles wishing us a “happy new year,” though fearful of what kind of a reception we would give them. We received them kindly, enquired where they came from and what the news was down the river, and then sent them to division headquarters. I counted twenty one in the company.

Diary of Sam Webster, Co. D, 1863

Excerpts of this diary (HM 48531) are used with permission from The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA

In camp at same place - on place of Mr. Bowie, near Fletcher's Chapel, and not a great way from Belle Plain Landing.

Monday, January 12th

Monday, January 12th

Sutler [William Chase and William H.

Brown] got to

camp

with goods. Chief

amusement of camp is playing cards; chief drawbacks, drills,

inspections and

storms; all very plentiful; chief pleasure in the line of rations, the

edition

of potatoes. Have

had marching orders

once.

Baked beans for breakfast – regular Yankee dish. Bake them “thusly;” Dig a hole a couple of feet deep and wide, and build a huge fire in it. At the same time have the beans “parboiling.” When the beans are ready put the kettle in the hoe, put a piece of pork in on top of the beans, invert a mess pan over the kettle, fill in about it with live coals until well covered; then put some earth on the coals, and build a fire over all. Generally do this at night, and in the morning we have them for breakfast nicely baked, forming a nice addition to the usual rations. Our camp on a hill, nicely drained on either side.

Thursday, January

15th

Very windy – tent shaking back

and

forth like a rag on a

bush, almost. Spilled

my ink over my

knapsack, and then dusted it with lots of sand.

Capt. Hovey is detailed for Brigade Inspector. Will look out

for frills,

bright brasses, and

polished guns. Ducks

going south – sign

of cold weather.

Tuesday, January 20th

Regiment was on picquet yesterday,

coming off late last

night. Marched at

noon today. Crossed

R.R. near where Ord’s headquarters

were last spring. Got

cut off from the

rest of the Brigade by some batteries, and only found them, late, in a

hard

rain. Pitched tent

under various

disadvantages. Could

find no wood, and

so went to bed on a “dry supper.”

No

crotches for tent, so “pitched” it over two guns set on end, the two

guide

lines being made fast to keep it from sagging in the middle.

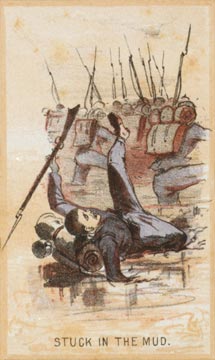

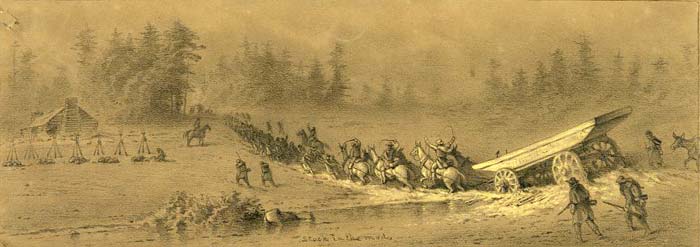

Burnside's Mud March, January 20 - 23, 1863.

GENERAL ORDERS,

HEADQUARTERS ARMY OF THE POTOMAC,

Number 7.

Camp near Falmouth, Va., January 20, 1863.

The commanding general announces to the Army of the Potomac that they are about to meet the enemy once more.

The late brilliant actions in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Arkansas have divided and weakened the enemy on the Rappahannock, and the auspicious moment seems to have arrived to strike a great and mortal blow to the rebellion, and to gain that decisive victory which is due to the country.

Let the gallant soldiers of so many brilliant battle-fields accomplish this achievement, and a fame the most glorious awaits them.

The commanding general calls for the firm and united action of officers and men, and, under the providence of God, the Army of the Potomac will have taken a great step toward restoring peace to the country and the Government to its rightful authority.

By command of Major-General Burnside:

LEWIS RICHMOND,

Assistant Adjutant-General.

Letter of Captain Elliot C. Pierce

Elliot C. Pierce to Mary Baker, 22 January, 1863; Thayer Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society. Used with permission.

Yours of the 16th is at hand

Bivouac. Near the

Rappahannock west of

Falmouth Va. Jan22/63

My dear Mary

We Moved Tuesday Morng and at night a

severe storm of wind + rain came upon us, we still Marched

till Yester-eve. And here, what that is left of the Army of Potomac,

are stuck fast, + stuck deep in the Mud

Such a sight as the Army now presents never was seen before I fancy – We are stuck in the Mud – bivouacked in the Mud – sleep, in Mud – eat, in Mud drink, in Mud. If we do Move, we shall Move in Mud. I am sitting in Mud as I write – do not wonder therefore if I sign Myself

Yours

Muddily

Elliot

From Three Years in the Army; by Charles E. Davis, Jr., Boston, Estes & Lauriat; 1894.

January 20. Orders were received to march. We were told that we were to cross the river once more and engage in an effort to turn the right wing of the enemy. Possibly Burnside was in possession of information that led him to believe this could be done, though we did not believe it. As will be seen, this turned out to be a “holler mockery.”

We had become fairly well settled in what we supposed would be permanent winter quarters, so we were not moved to mirth or joy on receiving the order to march. In answer to our inquiries of what was up, we were informed that we were to cross the river and attack the right wing of the enemy posted on the opposite bank. It was said that Burnside had received information that the enemy had become so weakened by the withdrawal of troops, that a victory might be gained with the possibility of our marching on to Richmond. The breaking up of our camp was attended by the usual destruction of things that had contributed to our comfort and pleasure. Some of the huts were burned, and a general scene of disorder prevailed as we left the spot. About noon we started and marched in a westerly direction ten miles, to Stonemans’ Switch, where we halted for the night. This was the beginning of what has since been known in war literature as “Burnside’s mud march.” We had sampled from time to time the “sacred soil” of Virginia, but in the wildest dreams of our imagination we had seen no mud like this. As usual, after a few weeks of continuous camp life, our knapsacks had assumed a plethoric appearance out of keeping with the hard work before us. When a soldier leaves a camp such as ours had become, he has to consider what he will throw away. Idleness is what fattens a knapsack. A soldier generally starts with a good deal more than he can carry, but his back, which is master of the situation, soon brings him to terms, and after a day or two the luxuries disappear.

Somehow or other we got separated from the other regiments in the brigade, and didn’t succeed in finding them until night, and then it was raining hard. As there was no wood to be had we could build no fires; and therefore no coffee; nor could we find sticks on which to pitch our tents, so our guns were forced to do duty in their place.

If some

ministering

angel had

happened round about this time

with a barrel of hot whiskey, well flavored with lemon-peel and sugar,

it is

doubtful if any soldier would have said, “get thee behind me,

Satan!” There may have been one or

two, or even three

or three and a half men, whose powers of articulation would have become

so

paralyzed at the thought as not to be able to exclaim with the rest of

us,

“Down with rum !” though we doubt it.

If some

ministering

angel had

happened round about this time

with a barrel of hot whiskey, well flavored with lemon-peel and sugar,

it is

doubtful if any soldier would have said, “get thee behind me,

Satan!” There may have been one or

two, or even three

or three and a half men, whose powers of articulation would have become

so

paralyzed at the thought as not to be able to exclaim with the rest of

us,

“Down with rum !” though we doubt it.

Wednesday, January 21. It rained hard at daylight, and so reveille was skipped. Every drop of rain deepened and liquefied the mud. Surely such a sigh was never before seen as an army struggling to make headway in such a mess. Batteries and wagons could be moved only by doubling the number of horses, and even then it frequently happened they became fast imbedded in the mud. As they moved along in their jerky and twisting way, the axle-trees would scrape the top of the soil.

Toward noon we started again, and after six hours of dreary labor we made only four and a half miles. As we marched along the road we saw displayed by the enemy on the opposite bank of the river placards bearing the words, “Burnside’s army stuck in the mud.” Not only that – we were jeered at by the “rebs,” who were highly pleased at our efforts in puddling. Add to it the mortification of finding our powder wet, one can form some idea of our hopeless condition.

At the end of our

four and a half

miles the order was given

to halt for the night, and it came none too soon.

No wonder the “Mud march” has become one of

the historical episodes of the war.

At the end of our

four and a half

miles the order was given

to halt for the night, and it came none too soon.

No wonder the “Mud march” has become one of

the historical episodes of the war.

Thursday January 22. We remained quiet all day. The pitiable condition of the army must have shown the uselessness of attempting a movement against the enemy at such a time. We received half-rations last night, and being encamped near a forest, were able to get wood for fires, and so managed to make life endurable. Fence rails had become very scarce. As the warmth of the fires stole over the boys, they began, as usual, to turn their misery into fun, though there was nothing very hilarious about it.

Friday January 23. We got away at 8 A.M. and waded back through the mud to our camp at Fletcher’s Chapel, a distance of fourteen miles. It was a hard day’s work, but the boys were encouraged by the fact that each step shortened the distance to our supplies. We soon forsook the road for the fields and woods, wading brooks and jumping ditches, glad at any progress toward the camp we left on the 20th.

We found the camp in a sorry condition, from the rain and the disorder in which we left it. Those of us who destroyed our huts when we left this spot on the 20th felt badly enough as we gazed on the ruins.

The camp was soon restored to a moderate degree of comfort; fires were lighted and coffee made, whereupon there ensued a lively discussion on the monumental stupidity of our recent movement. If a general officer could have been present, unseen, at a gathering of private soldiers round a camp-fire after a battle, or after a movement such as the one we have just described, he would have heard some plain, instructive talk. We were pretty unanimously of the opinion that “Old Abe” had better appoint a private soldier to run the next campaign. As our huts assumed a condition of comfort, like Jove, we smoothed our wrinkled fronts, and settled down to another period of camp life.

It is not

an

exaggeration to say,

that before or after,

there was seen no such state of demoralization as possessed a large

part of the

Army of the Potomac

at the end of this foolish

undertaking. On our

return march, men

were seen straggling back to their camps, cursing everything and

everybody. Strewed

along the road lying

in the mud could be seen knapsacks, guns, and equipments, thrown away

by men

thoroughly disheartened by fatigue and hunger; the very men who had

fought

uncomplainingly a few weeks before, as indeed they would do again when

their

confidence and spirits were restored, had become more incapacitated by

the

terrible condition of the roads than by a battle.

Strewed

along the road lying

in the mud could be seen knapsacks, guns, and equipments, thrown away

by men

thoroughly disheartened by fatigue and hunger; the very men who had

fought

uncomplainingly a few weeks before, as indeed they would do again when

their

confidence and spirits were restored, had become more incapacitated by

the

terrible condition of the roads than by a battle.

When the papers of January 20 reached us, the first item about the Army of the Potomac that caught our eyes was headed, ”A Desperate Struggle is Evidently Close At Hand, And Stirring News May Be Expected Shortly.” The “Mud March” was finished, and we could gaze on this announcement with unruffled tempers, being in a thankful mood. Our experience suggested that this might be a witticism, for the struggle through the mud was both stirring and desperate. In the papers of the 19th the statement was made: “On To Richmond Again! – It is now deemed certain that General Burnside is by this time across the river, and the rebels are skedaddling inland.” “Brag” is a good dog, but “Hold Fast” is a better. Some of the boys suggested that these papers be sent to General Lee as an item of news, but when we thought of the disgraceful predicament we had been in, squirming about in the mud like so many eels, we concluded not to do so.

Memoirs of John S. Fay, Co. F

The hand-written memoirs of John S. Fay were donated to the Fredericksburg National Battlefield Park by Fay's descendant, Mr. Peter Bolan, who also shared some biographical materials on Fay with me, including the image of Fay below. John Hennessy shared the manuscript with me so I could use it on the website.

John S. Fay picks up his narrative from where it left off after Fredericksburg [See the Fredericksburg page of this website.]

We built winter quarters and improved our camp so as to have everything as comfortable as possable. A comrad and my self built us a house by digging a hole in the ground about ten feet long six feet wide and two and a half feet deep. We then split slabs from pine logs and fastened them up to the sides by driving stakes into the ground, the slabs extended about a foot above the top of the ground. We then pitched our shelter tents over this for a roof.

We made a fire place in one end, by digging a hole in the bank and a hole from the back part up thrugh to the top of the ground, over which we built a chimney of stiks plastered on the inside with mud, there is so much clay in the soil that it will dry most as hard as a brick.

On the 20 of January (1863) Gen Burnside attempted another on to Richmond movement. We started in the afternoon and marched up the river about six miles and bivouacked for the night. All the time we had been in camp since the battle of Fredericksburg it had been remarkable pleasant weather for the season, but it commence to rain so hard that we could not sleep any. We started agin in the morning and marched about four miles, when we got stuck in the mud and could not neither advance or retreat for two days. All this time it was raining very hard a cold northeast storm.

On the second day we got out of rations “we started with only two days” and the mud was so deep they could not get any supplys to us.

The mud was from six inches to six feet deep in the roads and many horses and mules died while floundering in the mud, and it was so cold that several men chilled to death while resting by the road side, having became so exausted from wet and exposure that they could go no farther. On the morning of the 24 we was ordered back to our camp. It took us all day to march ten miles the distance back to our quarters. We got some rations that night the first we had had for two days.

This movement was called Gen Burnside’s stuck-in-the-mud-march. Soon after this Gen Burnside was releived from and Gen Hooker took command of the Army of the Potomac, and we very soon saw there was better management in the commissary department. Gen. Hooker gave us better rations and more of them than we ever had before.

While we was under Gen Burnside we had poor rations and less in quantity, than we ever had except the first three or four months that we was in the service. All the time Gen. Burnside was in command of the army, there seemed to be a continual disagreement Among the officers of the different departments, so that there was not that efficiently shown in neither the Ordnance Quartermaster’s or commissary departments as there should have been. So that we did not have proper clothing, or rations and when in battle we was not properly supplied with ammunition.

Letter of Dennis G Walker

This letter of Walker's tells about the "Mud March." I've made a few paragraph breaks to rest the eyes of the reader. Digital transcription is by David Walker, who shared the letters with me.

Camp Near Fletchers Chappel VA

Jan 25th 1863

Dear Father,

I received your letter of the 1 first and I glad to hear from yo and glad to hear that yo and the rest of the famley ar in such good health with the exseption of your legs and I hope that this will find yo all well and your legs groin stronger.

I am sorry to hear of the death of Mr. Morill. I always thought a great deal of him and I should of liked to sean him once more. I hav often thought of him sinc I hav Ben out hear and Mad several atempts to write him But I neglected to do so I think he was a good old man. At least I am indeted to him for his kindness that he has shown toward me.

I hed a letter

from Winfield the other day and also one from George and Hiram Gustin

and thay

was all well and having a good time and an easey one. But

they do not think so

thay ar not contented. But if thay could Be in this army of

the Pertomac Just

one weak thay would go Back contented. But it is not natueral

for a soldier to

be conted. So I can not blame them for thay do not no what

thay ar disconted

with. But thay may hav a chance to find out altho I hope thay

will not.

Winfield sayd that he was a goin to get his discharg he sayd

that he should not

write home until he gut Paid of and gut som Post stamps. He

has not heard from

Lewis latley. I would write to Lewis But I do not hav much

time to write

another. I do not no as he would get it But I dont think that he is in

Tennesee. He is not farther the Missippi then Vicksburg.

I tink that I will

write him soon I have gut no Post Stamp to Pute on this letter But I

thought

that I would write if I hed to Pute on Soldier letter.

I hed a letter

from Winfield the other day and also one from George and Hiram Gustin

and thay

was all well and having a good time and an easey one. But

they do not think so

thay ar not contented. But if thay could Be in this army of

the Pertomac Just

one weak thay would go Back contented. But it is not natueral

for a soldier to

be conted. So I can not blame them for thay do not no what

thay ar disconted

with. But thay may hav a chance to find out altho I hope thay

will not.

Winfield sayd that he was a goin to get his discharg he sayd

that he should not

write home until he gut Paid of and gut som Post stamps. He

has not heard from

Lewis latley. I would write to Lewis But I do not hav much

time to write

another. I do not no as he would get it But I dont think that he is in

Tennesee. He is not farther the Missippi then Vicksburg.

I tink that I will

write him soon I have gut no Post Stamp to Pute on this letter But I

thought

that I would write if I hed to Pute on Soldier letter.

This is the first letter that I ha ever sent sinc I hav Ben a soldier with out a Post Stamp. But I hav gut all out now But I chal get som this weak from Boston. I hav anney quantity of letters com to me marked 3 cents due But I do not hav to Pay. But I suppose yo will hav to Pay for this. I hav not Ben Paid yet and I do not cair much now if I never do.

We have hed a hard March sinc I wrote yo last and the mud is anny whair from 1 one foot to 3 in this Part of the country we go on Picket By Brigad hear and it was ower luck to Be on last Monday night and we hed orders to go Back to camp at sun rise on Tuesday morning and Pack up and get ready for a March. We Broke camp Tuesday noon and Marched for falmouth the Road was crowded with troops and we Marched throo wood and fields and crost lots and a bout dark that knight it comenced to raine But we did not stop for that at last we gut in to a larg colum of troops and gut Broke up and lost ower Brigade so thay Kep us a moving until a bout 10 o clock that night we found ower Brigade and halted for the night it still Kept raining and grew muddier next Day. we gut wet throo same as we Generaley do Be fore we halted. But we soon Pitched ower day houses and craled in to them to get out of the way of the rain. it was cold and dark so we did not get anny supper But went to sleep.

the next morning we was a wak at 5 o clock and ordered to strik ower day houses and March so we did not hav time to get anny Breakfast. it still rained and hed Ben doing so all night hard and we was soaking wet the watter hed run under ower tent and wet ous all throo. a Blanket that Generaley weights 5 lbs then weight 10 or 12 But in less then 10 minutes we Puled up sticks and was on the road in the mud half way to ower knees it was hard Marching.

we past Artilery stuck fast in the

mud and also teams. We still Marched on with ower

heavey Packs on the first

halt was mad a bout 12 oclock we hed Marched over

6 hours with out a halt with

out anny Breakfast and with a heavey load

we Marched in this time a bout 5

milds every step going half way to ower knees.

the Regts or Brigades did not

March in colum But Marched in droves

the men was scatered for milds and anny

one would of thought to of sean ous that the army was on a gran

Retreat. it

looked wors then Bull Runn No. 2.  the men threw a

way thair guns and equipments [[unintell.]] sacks

and many of them threw a way thair Knapsacks and Blankets

the road was lined with such stuff. I Be gun to

think my self that the armey

was getting demorilesed. it still rained and we halted for

good at 12 o clock

and it rained all of that knight and the next day ower rasions Run out

and the

teams could not get up with rasions.

the men threw a

way thair guns and equipments [[unintell.]] sacks

and many of them threw a way thair Knapsacks and Blankets

the road was lined with such stuff. I Be gun to

think my self that the armey

was getting demorilesed. it still rained and we halted for

good at 12 o clock

and it rained all of that knight and the next day ower rasions Run out

and the

teams could not get up with rasions.

So the Gran movement was Prosponed and we started Back on Friday with out anny rasions and we did not get anny until yester day noon. That was the toughest March that I ever gut a great many men dide with exsposier and a great number Diserted and thair was horses with out end stuck fast in the mud and a great many ded one lay a long the roads.

That was a gran movement But I think we a complished as much as we should if we hed of crost the River for we should of gut licked and hed 15 or 20 thousan killed the Jolley Rebs was readey for ous thay lay on the opersit side of the River laughing at ous for thay Knew what kind of a mud hole that we hed gut in to. thay hed a figure made out of rags stuck up in the mud Marked on it, Burnside, stuck in the mud.

this is a grand army But I should advise old Abe not to giv them anny Grean Backs if he dose I think the men will go Back on him. we ar now in ower old camp But I exspect that we chal move a gain soon or this armey will Be split up and a part of it sent down South. I think that this war will close By spring and I do not think that it will Be closed By fighting either. But as I am getting tired I will draw to a close.

Digital transcription by David Walker

Letter of Charles Leland, Company B - Mud March

The Pearce Museum at Navarro College holds nine letters written by Charles Leland of the '13th Mass.,' in their collections. Other items of interest include, John A. Boudwin's 1863 diary, (Boudwin was in Company A) and 11 letters written by Oliver Walker who started out in the 13th Mass, Company C, and transferred to the 24th Mass. Regt. in December, 1861. Walker was eventually killed while serving with the 24th.

The money received by the Pearce Museum for providing transcriptions of these materials helps maintain the collection, so I am very grateful that they allowed me to present 2 of Charles's letters here. For More information, click on the logo to visit their site.From the collection of the Pearce Museum, Navarro College, Texas. Used with permission.

Camp near Bell Plain Landing

Jan 25th 1863

Dear Father,

I received your good letter No 4 some time

ago and meant to have answered it, but the famous

move in which we got stuck in the mud prevented.

However here we are back in our old quarters

living the same as ever.

I will probably get my box tomorrow or next day.

We got paid off today, we got four months pay instead of 7 that they owed us.

I shall not send any home this time as we pay our sutler, and it will not leave a great deal over.

That was a splendid story in Frank Leslie’s, but then I wish you could see how the army feels.

There is a very bad feeling all through the army of the Potomac, and I will tell you what began it. It was the removal of McClellan.

You cannot find scarcly a man but what almost loved him if I may use this expression.

The government have not

paid us and it seems as if we

were moved around, not by the judgement of our Generals as by the red

tape at Washington,

and the growling of the people at

home.

The government have not

paid us and it seems as if we

were moved around, not by the judgement of our Generals as by the red

tape at Washington,

and the growling of the people at

home.

The army is discouraged and disheartened. Things look discouraging enough to me but I would die rather than desert. If the country goes to the devil I go too.

What do the people at home think of this war.

There will be thousands desert after pay day. I know that there are citizens who will help them.

The government had ought to let the Generals alone.

We are now on the last half of our enlistment and have a little over 17 months more to serve.

Our regiment went out on picket the day before we moved to attack Johnny Reb. and the next Am were ordered in, took our knapsacks and rations and left in the rain.

When we arrived at White-Oak Church, about half way to the river, Burnsides Proclamation was read.

You will probably read in Newspapers that we cheered &c as two or three reporters were with us. but we didn’t.

When we got within a mile of the river we halted and staid overnight in the woods. Mean while the mud had got so deep that the artillery could not be moved and so the grand movement bust up.

I like Burnside as I think he had orders from Washington, and had to move.

Winter campaign is played out. I guess we will stay here for some time in fact may not move before Spring.

I suppose that business is good at home. They say that Rosencranz is in rather a tight fix in the West but I hope he will get out all right.

I am very sorry to hear that Aunt Mary is not well but hope that she will recover soon. Remember me to her and Uncle [Alexander] when you write.

I am glad to hear of Clarks recovery and hope that he will have a good time before he returns.

I will write as soon as I get my box and hoping you will write soon with much love to Mother, Henry and little sister Ada, I am your affectionate son

Chas. E. Leland.

Transcribed by Betty Evans; Digital Transcription by Brad Forbush

Resignation of Major-General Burnside

General Burnside having requested to be relieved from the command of the Army of the Potomac, the following order was issued:

General Orders

General Orders

No. 9

Headquarters Army of the Potomac,

Camp Near Falmouth, Va.

Jan. 26, 1863.

By direction of the President of the United States, the Commanding General this day transfers the command of this army to Maj.-Gen. Joseph Hooker.

The short time that he has directed your movements has not been fruitful of victory or any considerable advancement of our lines, but it has again demonstrated an amount of courage, patience, and endurance that under more favorable circumstances would have accomplished great results. Continue to exercise these virtues, be true in your devotion to your country and the principles you have sworn to maintain, give to the brave and skilful general who has so long been identified with your organization and who is now to command you, your full and cordial support and cooperation, and you will deserve success.

In taking an affectionate leave of the entire army, from which he separates with so much regret, he may be pardoned if he bids an especial farewell to this long tried associates of the Ninth Corps. His prayers are that God may be with you, and grant you continual success until the rebellion is crushed.

By command of Major-General

Burnside,

Lewis Richmond,

Assistant

Adjutant-General.

A good deal of confidence was restored by the appointment of General Hooker – or “Fighting Joe,” as the boys called him.

From "Three Years with Company K"; 1976 Fairleigh-Dickenson Press; p.155-157; Used with permission.

"Games Played by Boys" Austin Stearns wrote:

Burnside asked to be releived from his command, and his request was granted, while Joseph Hooker was appointed in his place. The appointment of Hooker gave unbounded satisfaction to the boys, and among some of the first of his orders were that the troops should receive a ration of vegetables twice a week, and soft bread every day and if the commissaries could not furnish them, he wanted to know the reason why. Soft bread was forth coming to us every day, and I never knew of an instance where it could not be furnished. The troops had confidence in “Old Joe” and, with the change of rations, were in the best of spirits. We amused

ourselves as best we

could. Playing cards was the most favorite. I

remember of playing, one stormy day with three comrades, over eighty

games of Euchre without going out of our tent. Putting old

blankets over the top of a chimney so the smoke could not escape and

giving the inmates a taste of smoke was another. Jim Slatery

and Mike O’Laughlin tent was the one next to mine. One day

when they had a good fire Al Sanborn put a piece of old blanket down

their chimney, stopping the smoke completely, and soon their tent was

full. Looking out they could see nothing the mater and

concluded it was the poor draught, and not wishing to have the laugh on

them, went back and thought to stay it out, but he smoke from

the green pine wood wet with pitch was to much for them and out came

Slatery to look around. The boys, some of them seeing the

smoke pouring from every seam, and always ready to laugh at anothers

misfortune, came crowding around laughing to see the fun with such

exclamations, as “Mike and Jim are going into business smoking sides,

and are trying their tent now to see if it will hold smoke.”

At length one suggested that they look into their chimney, and Jim,

doing so, pulled out a piece of blanket; the smoke then came out in

torrents. “By Gard” said Slatery, “I knew it was that Sanborn

all the time.” Mike and Jim, being very honest men, received

their full share of games.

We amused

ourselves as best we

could. Playing cards was the most favorite. I

remember of playing, one stormy day with three comrades, over eighty

games of Euchre without going out of our tent. Putting old

blankets over the top of a chimney so the smoke could not escape and

giving the inmates a taste of smoke was another. Jim Slatery

and Mike O’Laughlin tent was the one next to mine. One day

when they had a good fire Al Sanborn put a piece of old blanket down

their chimney, stopping the smoke completely, and soon their tent was

full. Looking out they could see nothing the mater and

concluded it was the poor draught, and not wishing to have the laugh on

them, went back and thought to stay it out, but he smoke from

the green pine wood wet with pitch was to much for them and out came

Slatery to look around. The boys, some of them seeing the

smoke pouring from every seam, and always ready to laugh at anothers

misfortune, came crowding around laughing to see the fun with such

exclamations, as “Mike and Jim are going into business smoking sides,

and are trying their tent now to see if it will hold smoke.”

At length one suggested that they look into their chimney, and Jim,

doing so, pulled out a piece of blanket; the smoke then came out in

torrents. “By Gard” said Slatery, “I knew it was that Sanborn

all the time.” Mike and Jim, being very honest men, received

their full share of games.

John Gliddon, a good soldier and a hard working man, was detailed as a pionier, and was working every day helping to build a corduroy road, going to his work early in the morning and remaining till dark, and in addition doing his own cooking.

One night after coming home, tired as he was, cooking his supper, some one dropped a lump of earth down his chimney, spilling his coffee and making his meat unfit to eat. John was mad, and seizing his gun rushed out with his war, warrr (for you could not understand him much better then a blackbird) [and] threatened to shoot the man who did it. The boys, hearing the rumpus, quickly gathered around, and when learning what the matter was, condemned it in strong terms; while enjoying a harmless joke, to spoil a mans supper was too serious a thing to be overlooked, and if the guilty one had been found John would have been permitted to like him without any danger to himself. It was never known for certain who did it, but we all thought of the same man, and that was Al Sanborn. We contributed our store and John did not go to bed supperless. (Massachusetts soldier Charles W. Reed sketched these soldiers "Tipping a Chimney." )

Diary of Sam Webster

Excerpts of this diary (HM 48531) are used with permission from The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA

January

25th Paymaster got here. Payed off thru Co's for 4

months -

rest is to be paid tomorrow. Another inspection.

January

25th Paymaster got here. Payed off thru Co's for 4

months -

rest is to be paid tomorrow. Another inspection.

January 26th Paid Off. Got $42. Owed the Sutlers $6. Brigade Inspection.

Thursday, January 29th

Found myself covered with snow, on

awakening, and the tent

pretty well filled from drifting.

Day

clear but very cold. On

guard.

Friday, January 30th

Rations of dried apples

issued. John

Watts “affected.”

He “cussed” Capt. Harlow,

fired his gun into

the fire, and tumbled into Whitney and Miles’ tent all within a few

minutes. He

had

been down to the Brigade

Commissariat with Kelly and others on a working party and the

“commissary

whisky” proved too much for him.

They

were building ovens for baking bread. The ovens are

made by smoothing a place 8 or 10 feet wide,

and as many –

or more – long, on which place are laid the half-cylindrical sheets of

iron

which compose the ovens.  They

are of

sheet iron bent in shape of diagram in margin, about four feet across

and two

deep. Two or three

are placed

continuously end to end, the back end bricked up, and a chimney built,

and the

oven is complete. Two

or three of these,

according to the size of the brigade, are placed side by side, and then

covered

with earth a foot or two deep. Pans

are

provided holding a given number of loaves – each loaf being 1 days

ration for 1

man – and suited to the size of the ovens.

By this means the army is provided with good fresh bread

every day, as

each brigade has its own bakery. We

scarcely see hard bread anymore, and our supply of food is

correspondingly

better.

They

are of

sheet iron bent in shape of diagram in margin, about four feet across

and two

deep. Two or three

are placed

continuously end to end, the back end bricked up, and a chimney built,

and the

oven is complete. Two

or three of these,

according to the size of the brigade, are placed side by side, and then

covered

with earth a foot or two deep. Pans

are

provided holding a given number of loaves – each loaf being 1 days

ration for 1

man – and suited to the size of the ovens.

By this means the army is provided with good fresh bread

every day, as

each brigade has its own bakery. We

scarcely see hard bread anymore, and our supply of food is

correspondingly

better.

GRINS

By Clarence H. Bell, Bivouac, February, 1885.

As time in its flight removes us to a greater distance from the days of our campaigning, we are prone to gild with the tinsel of the ludicrous the experiences of the war that were at the occurrence very serious moments of reality. Two or three old veterans will meet together, and will laugh over some perilous adventure, or some hair-breadth escape, remembering only the comical side of the affair, utterly oblivious of the fact that at the time the faces were of the longest, most serious nature, and the grins, did any occur, were of the dreariest variety. The “Mud-march,” when we floundered along in the mire, drenched to the skin by the cold, penetrating rain – when if any one had perpetrated a joke, or spoken a pleasant word, he would have been instantly frowned upon as demented – excites now, as we talk over the experience, only the most boisterous mirth.

Our identity seems changed, as if some other fellow had enjoyed the dismal tramp; had worked so hard at the close of the day to start the flame among the wet fuel, that he had blown himself breathless and exhausted, and in his dripping clothing had rolled himself up in a wet blanket and shivered away till morning. Then the scanty rations ! We remember the many occasions when food was very scarce, and hunger very plenty, and we chuckle as we recall those days. Then the snapping bullets, and the shrieking shells, even these now excite our mirth, and we congratulate ourselves that we escaped with two-thirds or the whole of our anatomy. We are ready to have our laugh now, perhaps deluding ourselves into the belief that we did not have any then.

But let us look into the subject. Was it all hardship and suffering at the time? Were there no occasions when the camps or the bivouacs were as full of happy faces and bright smiles as a clear day is full of sunshine? Let us open the tomes of memory and cull a few pages of pleasant recollections – we shall find plenty of them to choose from, but will select only a few – times when we were all smiles, and when the voice of pleasantness echoed among the trees.

Can you remember any period of your army life when you gave yourself up to a larger fit of the “grins” than you did when you learned that the paymaster was on his way to the regiment? It had been many a long month since you had met him, and you yearned to renew the acquaintance. Your pockets had been free from the “circulating medium” since you could not tell when, and our credit at the sutler’s was thoroughly exhausted. You had borrowed from your comrades until the banks of friendship were at the extreme of tension, and you had swapped off everything of our portable property that was susceptible of barter. You had settled down into the conviction that all that Uncle Sam wanted of you was fighting, and was bound that you should die off without a dollar in your pocket; when one afternoon, somebody put his head into the entrance of your tent with the startling information:

“They’re hitching up an ambulance to go for the paymaster.”

It seemed to be

too good to be

true, and you had no faith in the tale until you had “piled” out and

had wended your way with the throng to the wagon-camp, where

preparations for the departure of the ambulance were being

concluded. How you envied the driver; you would rather have

had his place than have received a commission. You watched

the vehicle till it vanished from sight, and then you spread the

tidings until you came upon the growler, who hushed you up by informing

you, “That’s old news; tell us something

fresh.” On this you subsided,

but your

face wore the fixed grin, and the slightest attempt at wit caused you

to break forth into the most extravagant laughter. After an

hour or so, some one shouted: “Here he comes,” and

you rushed down to the entrance to the camp, accompanied by almost the

entire regiment, where you shouted yourself hoarse in voicing the

cheers that went up as the ambulance stopped at had-quarters.

To be sure you had some misgivings as the money-chest was

carried into the tent, it seemed to be so small – too small, in fact,

to pay off the multitude of men that were gathered about. You

thought that the national treasury would be hardly adequate to meet the

demand, and the fact that the box was carried into the colonel’s tent

served for an instant to excite your animosity. You felt that

he was to

have the first “show” at its contents, and you trembled at the dearth

that you feared was likely to ensue. According to your view,

the only proper custodian for those funds, the only individual that you

had absolute confidence in, was yourself; but after you had

noted the vigilance of the sentries as thy paced back and forth before

the headquarters; when you had been up there two or three

times, and found everything all right; when you saw the paymaster in

a distant part of the camp, contemplating the setting sun

through a tumbler partially filled with an amber fluid, held up to the

light, your confidence in mankind returned, and you retired to rest

with a mind free from turmoil, to dream of mints coining untold wealth

for your sole and particular benefit.

It seemed to be

too good to be

true, and you had no faith in the tale until you had “piled” out and

had wended your way with the throng to the wagon-camp, where

preparations for the departure of the ambulance were being

concluded. How you envied the driver; you would rather have

had his place than have received a commission. You watched

the vehicle till it vanished from sight, and then you spread the

tidings until you came upon the growler, who hushed you up by informing

you, “That’s old news; tell us something

fresh.” On this you subsided,

but your

face wore the fixed grin, and the slightest attempt at wit caused you

to break forth into the most extravagant laughter. After an

hour or so, some one shouted: “Here he comes,” and

you rushed down to the entrance to the camp, accompanied by almost the

entire regiment, where you shouted yourself hoarse in voicing the

cheers that went up as the ambulance stopped at had-quarters.

To be sure you had some misgivings as the money-chest was

carried into the tent, it seemed to be so small – too small, in fact,

to pay off the multitude of men that were gathered about. You

thought that the national treasury would be hardly adequate to meet the

demand, and the fact that the box was carried into the colonel’s tent

served for an instant to excite your animosity. You felt that

he was to

have the first “show” at its contents, and you trembled at the dearth

that you feared was likely to ensue. According to your view,

the only proper custodian for those funds, the only individual that you

had absolute confidence in, was yourself; but after you had

noted the vigilance of the sentries as thy paced back and forth before

the headquarters; when you had been up there two or three

times, and found everything all right; when you saw the paymaster in

a distant part of the camp, contemplating the setting sun

through a tumbler partially filled with an amber fluid, held up to the

light, your confidence in mankind returned, and you retired to rest

with a mind free from turmoil, to dream of mints coining untold wealth

for your sole and particular benefit.

At reveille you were up, and an

early

inspection satisfied you that everything was all right. Of course, you

were annoyed at the length of time that it required for the major to

consume his breakfast – you could have done it in half the time, and

catch twice as much – but you did not allow your impatience to efface

the grin that you had carried over from the previous evening.  Your company was not the first one to be paid, but when the men began

to scatter about the camp, with the new crisp “greenbacks” in their

hands; when you saw the crowd at the sutler’s tent pleading to be

waited on, you felt that it was surely a reality, and that your turn

would soon come, although you were slightly oppressed by the fear that

all the good things would be sold off before you could get hold of your

money. At last you heard the command: “Fall in company to

sign pay-roll.”

Your company was not the first one to be paid, but when the men began

to scatter about the camp, with the new crisp “greenbacks” in their

hands; when you saw the crowd at the sutler’s tent pleading to be

waited on, you felt that it was surely a reality, and that your turn

would soon come, although you were slightly oppressed by the fear that

all the good things would be sold off before you could get hold of your

money. At last you heard the command: “Fall in company to

sign pay-roll.”

“Thirteen dollars a month and found,” you shouted, and away from the end of the line came the response that you expected, “dead.”

How you laughed as the man in front of you signed his name, making such wretched work with his penmanship that you resolved that you would give them a sample of a first-class signature when you got the chance. At last you clutched the pen in your fingers, and with a few preliminary flourishes you spread yourself out. At the very beginning of the name the pen caught in the paper and snapped more than forty spatters of various shapes and sizes, occupying a radius of four inches, making your initial to look like the map of a bomb-shell exploding. You hurriedly finished the name, somewhat abashed, but reassured as you got your hand upon the bills that remained to you after the sutler had taken his liberal share. Then you scattered.

You hunted up Johnny, and paid the dollar you owed to him, and Sam sought you out and cancelled his debt. When you had “sponged off the slate,” and got your dis-charge from bankruptcy, you joined the press at the sutler’s tent, and leaning far over the rail, you frantically shook your money, as you beseeched the attendants to relieve you of your wealth. After a long time – such a long time ! – you got rid of your money, and elbowing your way through the boisterous crowd, you bore your precious freight to your tent. And what a cargo encumbered your arms! Canned peaches, condensed milk, plug tobacco, pickles, writing-paper, ink – memory refuses to yield half the catalogue. Your pockets were distended with ginger-cakes and sweet-crackers – so were your cheeks, while one hand held a small square package with the picture of a blue steamboat on the wrapper.

“No farther seek his merits to disclose,

Or draw his frailties from their dread abode.”

As you passed along to your quarters you were the very picture of satisfaction, contentment beamed in your eye, and pleasure wrinkled your face with a high-priced grin. There were smiles on the back of your neck. You had not experienced so much happiness since you were accepted as a recruit, and nobody envied you – everybody was basking in the rays of prosperity.

Spread the wings of your fancy, and fly back with me over more than a score of years to where the army, after weeks of campaigning, has at last established itself long enough for the issue of supplies. See the wagons from which are being unloaded boxes of clothing – shirts, coats, breeches, caps, shoes, everything, in fact, necessary to the renewal of the outward man. See the eager crowds about the cases; here is one trying on a coat, and hastily freeing himself from it as he finds it to be five or six sizes too big; and there is one, a stout giant, desperately wrenching himself from a garment as many sizes too small. His arms have penetrated the sleeves to such a depth that he seems to be all wrists and he is compelled to call for assistance in order to escape from his manacles. Here is a pile of shoes tossed about from hand to hand, as some individual with a small foot endeavors to cull a six from among the nines and tens.

“Anybody seen a six? I want a six, and these are all big sizes. I wonder if they thought the army was composed entirely of clod-hoppers?”

At

last every one finds what he desires – the throng diminishes, and all

that remains are a few garments of an extraordinary size that no one

can be coaxed into accepting. Note that happy fellow with the

entire

suit upon his arm; underclothing, shoes, everything necessary to a

complete outfit.  He stops at his tent long enough to extract

a towel and soap from his knapsack, then disappears in the woods.

Follow him until he comes to a brook. He flings his new

apparel upon the grass, and carefully jumps the stream to disrobe upon

the farther side. In the water at last. Did you ever see a

more joyous person as he splashes the liquid about, and the suds of his

ablution float down the brook to where a neighboring regiment obtains a

drinking supply. As he steps ashore and arrays himself in his

new toggery, see the grins chase each other over his countenance.

He

feels as if he was brand new outwardly and inwardly as he saunters back

to camp. Suddenly he stops, and a shadow of dismay usurps the

place of

the smile; he dashes back to the stream, and securing a boulder of

goodly size, he carefully deposits it upon his cast-off garments, and

with an air of triumph he hies himself hence-ward, occasionally looking

back as the possibility of pursuit smites his mind. Next we

find him at

the sutler’s, where he invests fifteen cents in a five-cent cigar, and

holding it in his mouth at an angle of forty-five degrees, he struts

about the camp, both hands in his pockets, as big as Billy B. D---; yes

bigger.

He stops at his tent long enough to extract

a towel and soap from his knapsack, then disappears in the woods.

Follow him until he comes to a brook. He flings his new

apparel upon the grass, and carefully jumps the stream to disrobe upon

the farther side. In the water at last. Did you ever see a

more joyous person as he splashes the liquid about, and the suds of his

ablution float down the brook to where a neighboring regiment obtains a

drinking supply. As he steps ashore and arrays himself in his

new toggery, see the grins chase each other over his countenance.

He

feels as if he was brand new outwardly and inwardly as he saunters back

to camp. Suddenly he stops, and a shadow of dismay usurps the

place of

the smile; he dashes back to the stream, and securing a boulder of

goodly size, he carefully deposits it upon his cast-off garments, and

with an air of triumph he hies himself hence-ward, occasionally looking

back as the possibility of pursuit smites his mind. Next we

find him at

the sutler’s, where he invests fifteen cents in a five-cent cigar, and

holding it in his mouth at an angle of forty-five degrees, he struts

about the camp, both hands in his pockets, as big as Billy B. D---; yes

bigger.

Right here comes to mind an

incident of the second summer of our

service. We were in Sibley tents, about fifteen occupying our

particular cone. We had had many debates upon cleanliness,

and every one had settled to a determined effort to free himself from

the “pestilence that walketh in darkness.” Having

gathered

our messmates together, we carefully tied up the entrance to our

habitation, and every man sat in his allotted space unencumbered by any

garments, busily engaged at his nitting

work. It was a very

exciting “skirmish,” and was conducted in the utmost silence,

completely isolated from the inquisitive multitude. We were

suddenly

aroused from our task by some person fumbling at our tent-strings,

endeavoring to effect an entrance. One can hardly imagine the

look of disgust that flitted around the enclosure as we glared at one

another to detect who was missing from our little band. Being

assured

that we were all there, our eyes unanimously sought the entrance in

time to see a leg encased in dark blue trowsers adorned with a broad

red stripe, thrust through the folds of the canvas. Great

John Pope – the New York Ninth !

Right here comes to mind an

incident of the second summer of our

service. We were in Sibley tents, about fifteen occupying our

particular cone. We had had many debates upon cleanliness,

and every one had settled to a determined effort to free himself from