We All Might Yet Receive The Same Honor

June 25th - June 30th 1863

"On The March To Gettysburg," by artist

Charles Copeland from "The Boys of '61" by Charles Carleton Coffin.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Whats on this Page

- We Are Veterans

- General Hooker Relieved; General Meade Takes Command

- "Bread and Tears"

- "You Have Insulted Ze Gener-al"

- "We Express Hope the New Commander will Show More Ability than His Predecessors"

- Emmitsburg, Before the Battle of Gettysburg

- Color Sergeant Roland B. Morris

Introduction

By June 23rd and 24th General Joseph Hooker who had been waiting “until the enemy develops his intention or force” understood his adversary, General Robert E. Lee planned a 2nd invasion of the north. But now Hooker needed to develop a plan of action..

Confederate General A. P. Hill’s three Divisions crossed the Potomac River at Shepherdstown June 24th. Confederate General James Longstreet’s Divisions approached Williamsport, Md., on the 24th and crossed the river on the 25th and 26th. General Richard Ewell’s Corps had been in Maryland and Pennsylvania gathering up supplies for the planned invasion since June 23rd. It was too late for Hooker to cut off General Ewell, something he initially considered until he discovered it was too late; the entire Confederate army was across the river.

Fortunately for Hooker, General Henry Slocum, commanding the 12th Corps at Leesburg, secured a river crossing for the Union army at Edward's Ferry. Two bridges there, were ready for use on June 25th.

By then General Hooker was ready - to a point. He would concentrate his army around Frederick, Maryland. A second series of long difficult marches was ordered to the various corps commanders to make up for lost time and catch up to the Rebels. To facilitate progress Major General John Reynolds was assigned command of the advance wing of the Army of the Potomac, consisting of the 1st, 3rd, & 11th Corps. Reynolds personally supervised the river crossings at Edward's Ferry on June 25th. His force moved to secure the mountain passes of South Mountain. This protected the rest of the army as it crossed the Potomac, in the event Lee might try to move east from the Cumberland Valley. The rest of the Army followed Reynolds across the Potomac toward Frederick on the 26th. By the night of the 27th both armies were north of the river. General Hooker skillfully shifted his base of operations 45 miles in 2 days.

The Quarrel with General Halleck

Then he got into a quarrel with General-in-Chief Henry Halleck. The argument was over the use of Federal troops at Harper’s Ferry.

Author Edwin B. Coddington* argues that it was Hooker’s confrontational tone with General Halleck, and the Lincoln administration, that cost him his job.

Hooker never really accepted Halleck as his superior officer or fully explained his plans to General Halleck. For a long time Hooker had an arrangement with President Lincoln to report exclusively to him, but Lincoln ended this arrangement on June 16th, ordering Hooker to discuss strategy with General Halleck, which was the proper chain of command. The two men disliked each other from pre-war days but Halleck tried to be accommodating while Hooker maintained a bad tone with his superior.

General Hooker wanted the 10,000 troops at the Harper’s Ferry Garrison for his counter move against General Lee. Hooker suggested to General Halleck the strategic Maryland Heights position opposite Harper's Ferry no longer served a useful purpose with Lee’s army already in Maryland. Being outnumbered, Hooker reasoned, the garrison force should be incorporated into the Army of the Potomac. He asked Halleck if there was any reason for holding the position. General Halleck replied that the Harper’s Ferry position had always been regarded as important, and he would not approve abandonment unless absolutely necessary.

Hooker sent an

angry response

to Halleck, listing all the reasons he could find to back his point of

view, and

he simultaneously requested the matter be presented to President

Lincoln and

Secretary

of War Edward Stanton for consideration. Without

waiting for a reply he then sent in his resignation on

grounds that with

the military means at his disposal he could not comply with original

instructions to cover both Harpers Ferry and Washington, D.C.

Author Coddington sites evidence that Hooker used his resignation as a club to bully Halleck into giving him a free hand with strategy. At this stage of the current crisis Hooker probably didn’t suspect Halleck would take him so seriously as to refer the matter of his resignation to President Lincoln. The timing of his resignation, concurrent with his July 27th orders to General Slocum to pick up two brigades from Harper's Ferry and move the 12th Corps to Williamsport, and Halleck’s response to the resignation, suggest this explanation. Hooker was uncompromising and unwilling to discuss the matter. He wanted the Harper’s Ferry troops to bolster the strength of his army. He left Halleck 2 choices; accept this proposal without question or accept my resignation.

Lincoln and Secretart of War Edwin Stanton did have doubts about Hooker’s ability to confront Lee in battle, ever since the disastrous Battle of Chancellorsville, and some evidence seems to substantiate the popularly accepted belief that the administration maneuvered to get rid of a man in whom it had lost confidence.

But General Halleck, somewhat in the dark never refused Hooker's request, and only asked for convincing arguments for the abandonment of the Harper's Ferry garrison.

In contrast, Hooker's successor, General George Gordon Meade also requested permission to withdraw a large portion of the Harper’s Ferry troops when he took over command on June 28th.. He had better use for the men elsewhere with Lee north of the Potomac. Halleck responded Meade could “diminish or increase” the garrison as he saw fit. Meade informed Halleck the next day that he had to abandon Harper's Ferry outright and carefully and tactfully explained his reasons for doing so. The whole affair illustrates the difference in tone between Halleck and the 2 generals. Meade reluctantly abandoned Harper's Ferry. Hooker's reasons were less clear.

General Halleck forwarded Hooker’s letter of resignation to President Lincoln who accepted it. With their faith already shattered as to whether Hooker would confront Lee, the President and General Halleck decided to appoint General George Gordon Meade to command the Army of the Potomac.

To those familiar with Meade’s military record, the administration made the right choice. Many commanders had lost faith in General Hooker’s leadership capabilities.

At 3 a.m. the morning of June 28th, a messenger on General Halleck’s staff delivered in person to General Meade, the orders placing him in command of the Army of the Potomac. It was not a request, due to the emergency of the situation. A letter from Halleck was included, (posted on this page below), explaining the specific powers granted him. Just before daylight General Meade arrived at General Hooker's head-quarters along with Colonel James A. Hardie, Halleck’s messenger. With good grace, Hooker accepted the notice relieving him of command and then spent some time briefing his replacement on the present situation. After the interview, at 7 a.m., Meade wired General Halleck in Washington D.C., formally accepting the command and laying out his plans.

Frederick,

Md., June

28, 1863 - 7 a.m.

(Received 10 a.m.)

General H. W. Halleck,

General-in-Chief:

The order placing me in command of this army is received. As a soldier, I obey it, and to the utmost of my ability will execute it. Totally unexpected as it has been, and in ignorance of the exact condition of the troops and position of the enemy, I can only now say that it appears to me I must move toward the Susquehanna, keeping Washington and Baltimore well covered, and if the enemy is checked in his attempt to cross the Susquehanna, or if he turns toward Baltimore, to give him battle. I would say that I trust every available man that can be spared will be sent to me, as from all accounts the enemy is in strong force. So soon as I can post myself up, I will communicate more in detail.

Geo.

G. Meade,

Major-General.

*"The Gettysburg Campaign, A Study in

Command," by Edward B. Coddington, First Touchstone Edition, 1997.

Whats on this Page

The narrative continues through June 30th, 1863, the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg. Charles Davis, Jr, Austin Stearns, Sam Webster and John Boudwin narrate the difficult marches north, in rainy weather for the most part. A short overview of the various Corps commanders assembled by General Hooker and inherited by General Meade is presented. Also included on the page are the last letters of Charles Leland, Company B, and a short tribute to popular color Sergeant Roland B. Morris, Company C. Both Leland and Morris were killed in action the first day at Gettysburg. An independent article, "Emmitsburg Before the Battle of Gettysburg," by historian John A. Miller, gives a peak into the lives of the citizens of Emmitsburg, Maryland, as the huge army of the Potomac rambled through.

The cartoon, "Lincoln's Dream, or There is a Good Time Coming," appeared in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, on February 14, 1863. Mr. Lincoln is asleep on a couch decorated with stars and stripes, and dreams of the generals whom he has beheaded for their shortcomings - McDowell, McClellan and Burnside - and of the members of his cabinet, Seward, Welles and Stanton, and of Halleck, Commander-in-Chief, who with bowed heads now await the axe. The artist was William Newman.

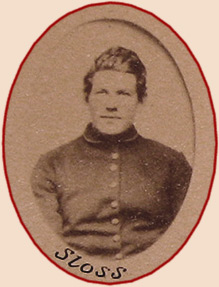

PICTURE CREDITS: All images & Maps are from the Library of Congress digital images collection, with the following exceptions: "Confederates Marching North," from American Heritage "Century Collection of Civil War Art," New York, 1974; Colonel Samuel H. Leonard, from Carlisle Amry Heritage Education Center [AHEC], Mass MOLLUS collection; George Worcester, Charles Leland, David Sloss, Edward Robinson & Joe Cary, from private collector and Antietam Expert Scott Hann; General Hartsuff at Petersburg, is from the digital collections of the Huntington Library, San Marino, Ca, specifically artist correspondent "James E. Taylor's scrapbooks."; Color Sergeant Roland Morris, from Tim Sewell; Appleton Sawyer was sent to me by Mr. Joe Stahl; pictures of the city of Emmitsburg, St. Mary's College and St. Joseph's are from the "Emmitsburg Area Historical Society" website, www.emmitsburg.net; Illustrations by artist Charles Copeland were accessed digitally via Googlebooks, from "The Boys of '61" by Charles Carleton Coffin and other works by the same author. The thumbnail illustration of the drenched soldier & the illustration, "Moontide & Evening" are from artist Edwin Forbes book, "Thirty Years After" LSU Press, Reprint, 1993; The beautiful French Illustration that accompanies "You Have Insulted Ze Gener-al" was done by artist Par H. De Sta, from "L'Alphabet Militaire" accessed digitally; ALL IMAGES have been edited in photoshop.

We Are Veterans

MAP - Situation

June 24, 1863.

This

map from the Library of

Congress, initially published in "Battles and Leaders of the Civil

War,"

shows Union and Confederate troop positions on June 24th,

1863.

I have tinted the Confederate blocks red, and the Union

blocks

blue. The map shows General Richard Ewell's Corps

(designated with an 'E') in

Pennsylvania at McConellsburg, Chambersburg and Greenwood.

General Peter Longstreet's Corps, (designated with

an

'L') is at Hagerstown, Md., and

General A. P. Hill's Corps, (designated with an

'H') at Boonsboro, Maryland. General J.E.B. Stuart's Cavalry,

(designated with an

'S') is

at Salem, Va., Ashby's Gap and Snicker's Gap in the Loudoun Valley, and

at Martinsburg, Virginia..

The Union Corps are designated with corresponding numbers. The 1st Corps is at Herndon Station, the 2nd Corps is at Gainesville and Thoroughfare Gap, the 3rd Corps is at Gum Springs, the 5th Corps is at Aldie, the 6th Corps is at Centreville, the 11th Corps is at Edward's Ferry, holding a river crossing, and the 12th Corps is at Leesburg, Virginia. Union home-guard militia, emergency troops, were being organized at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.

From "Three Years in the Army", by Charles E. Davis, Jr.

Thursday, June 25.

Information reached General

Hooker that General Lee had crossed the Potomac at Williamsport and

Shepherdstown, whereupon the First Corps was put in motion, and we

crossed the river into Maryland at Edward’s Ferry. Thence we

marched through Poolesville, where we spent a rainy night on Sept. 6,

1861, and then to Barnesville, where we halted for the night, having

marched about twenty miles.

They had an unobstructed road,

with a

purpose in view; while we were constantly delayed, not only from our

uncertainty of their movement, but the constant hindrance of our wagon

trains, which blocked the roads for hours. It was impossible

to move faster than the wagon train could go, as it would not do to

leave our supplies behind to be captured by Mosby or

Stuart. They had, while in

Virginia, a

great advantage over us in

this respect, as they could depend on the friendly hospitality of the

country, while we were obliged not only to carry our supplies, but to

protect them. When moving in the opposite direction, toward

Richmond, we were leaving our base of supplies while they were

returning to theirs.

They had an unobstructed road,

with a

purpose in view; while we were constantly delayed, not only from our

uncertainty of their movement, but the constant hindrance of our wagon

trains, which blocked the roads for hours. It was impossible

to move faster than the wagon train could go, as it would not do to

leave our supplies behind to be captured by Mosby or

Stuart. They had, while in

Virginia, a

great advantage over us in

this respect, as they could depend on the friendly hospitality of the

country, while we were obliged not only to carry our supplies, but to

protect them. When moving in the opposite direction, toward

Richmond, we were leaving our base of supplies while they were

returning to theirs.

We were now back in Maryland among the people we met in the summer of 1861. It seemed pleasant once more to see smiling faces and to be greeted with friendly words. The Union people of Maryland were very much disturbed as to what might happen if Lee was successful in his invasion of the Northern states. As we marched northward, the feeling took possession of us that we were now about to fight for our homes, and the impending battle would be one of intensity, though we were all in the dark as to where it might be fought. These people, whose friendly hospitality we had enjoyed two years before, were now in danger, and they looked to the Union army for protection, and without doubt this feeling had an influence in the events that followed.

*I have substituted the more accurate map above for the map in Charles Davis, Jr.'s regimental History.

From "Three Years with Company K," by Sergeant Austin Stearns, Edited by Arthur Kent, Fairleigh Dickenson Press; 1976. Used with Permission. (p 172 - 173).

How well I remember those long June days, the sun pouring down his hottest rays, through an unclouded sky upon us.

How

hot and dry the earth; huge clouds of dust could be seen far away to

tell where the army was marching. Dust was upon everything;

we

sweat, and the dust settling on our faces encased them as though in a

mold.

How

hot and dry the earth; huge clouds of dust could be seen far away to

tell where the army was marching. Dust was upon everything;

we

sweat, and the dust settling on our faces encased them as though in a

mold.

How glad we were when the order was given “to rest,” and, throwing off our traps, we stretched our weary selves on the grass and drank the delicious water of that cool spring in that little clump of trees. We had covered over ninety miles in three days.

The boys did not speculate much about what was going to be done, or the way to do it – that with many other things did not thrive after the first year. We were willing to let the events turn up without anticipating them; we were veterans, and as such were willing to do our duty, go when ordered, and obey even the minutest detail. We knew that Lee was marching his army through Virginia towards Maryland, and here from our elevated position could hear the guns and see the clouds of dust of his army. We knew that a collision was inevitable, but whether on Virginia or Maryland soil we could not tell; whether few or many days should intervene was a veiled picture to us. We had confidence in our officers and the whole spirit of the army was changed from one year ago, then we were boys, led by boyish men. Now we were men, tired men, and led by those who had been tried in many a battle and had not failed. Men and their officers worked together (that is those that were in the field), and the “old army of the Potomac,” from Hooker down to the little drummer boy, was working together; it was a Unit, and in unity there is strength. So the old army though small in numbers, was strong in the strength to win.

General Hooker Relieved; General Meade Takes Command

John Boudwin, Company A, starts off the narrative of this very long and very wet march to Middletown, Maryland from Guilford Station, Virginia.

Diary of Sergeant John Boudwin

June, Thursday, 25. 1863

Came in pleasant. Left

camp at Guilford Station at

9 A.M. and halted in road a short

distance from camp for 1 hour and started again and crossed the river

at

Edwards Ferry and marched through Poolesville, Md and camped for the

night at

Barnestown Maryland.

Went on Picket - rained

all night - distance

Marched - l7 miles.- a very hard march.

June, Friday, 26. l863

Left camp at Barnestown, Md.

at 4

A.M. Raining

very hard Marched

all day - Crossed the Monocacy River Sugar

Loaf

Mountain

and camped for the night at Jefferson Md...distance

marched l7 miles feel

used up every

thing

Wet. Dried

blanket and went down

Town my self and Sergt Cunningham and had a good supper

felt first rate - after it - had a good

nights rest.

June, Saturday, 27.

l863

Came in pleasant. Left

camp at Jefferson and marched to Middletown

distance 7

miles. going

through town several of the Women were

crying. arrived at Middletown

at noon

and went in to camp - mail arrived and received a

letter from Tom- Went to bed early and had a good rest.

Charles Davis, Jr.'s narrative continues; from "Three Years in the Army."

Friday,

June 26.

At 6 A.M. we marched over the

Catoctin mountains to Adamstown, through Greenfield’s Mill, across

Monocacy River, and thence to Jefferson, a distance of eighteen miles,

through the rain and mud. The route was circuitous, owing to

a

change made in the direction of our march, by orders from headquarters.

Saturday, June 27.

Marched to a mile beyond

Middletown, a distance of eight miles for the day. As we

passed through

Middletown we were greeted with the same kindly hospitality we met with

on our previous marches through this town.

The resignation of General Hooker, which is quoted in full, was accepted by the President:

Sandy Hook, June 27, 1 P.M.

Maj.-Gen H. W. Halleck, General-in-Chief:

My original instructions require me to

cover Harper’s Ferry and

Washington. I have now imposed upon me, in addition, an enemy

in my front of more than my number. I beg to be understood,

respectfully and firmly, that I am unable to comply with this condition

with the means at my disposal, and earnestly request that I may at once

be relieved from the position I occupy.

Joseph

Hooker,

Major-General.

In accordance with the terms of the following communication, General Meade was placed at the head of the Army of the Potomac:

Headquarters

of the Army,

Washington, D.C.,

June 27, 1863.

Maj.-Gen. George G. Meade, Army of the Potomac:

General: You will receive with this the order of the President placing you in command of the Army of the Potomac. Considering the circumstances, no one ever received a more important command, and I cannot doubt that you will fully justify the confidence which the Government has reposed in you.

You will not be hampered by any minute instruction from these headquarters. Your army is free to act as you may deem proper under the circumstances as they arise. You will, however, keep in view the important fact that the Army of the Potomac is the covering army of Washington, as well as the army of operation against the invading forces of the rebels. You will, therefore, maneuver and fight in such a manner as to cover the capital and also Baltimore, as far as circumstance will admit. Should General Lee move upon either of these places, it is expected that you will either anticipate him or arrive with him so as to give him battle.

All forces within the sphere of your operations will be held subject to your orders.

Harper’s Ferry and its garrison are under your direct orders.Your are authorized to remove from your command, and to send from your army, any officer or other person you may deem proper, and to appoint to command as you may deem expedient.

In fine, General, you are intrusted with all the power and authority which the President, secretary of War, or the General-in-Chief can confer on you, and you may rely upon our full support.

You will keep me fully informed of all your movements, and the position of your own troops and those of the enemy, so far as you know.

I shall always be ready to advise and assist you to the utmost of my ability.

Very respectfully, your obedient servant,

H.W.

Halleck,

General-in-Chief.

An

Announcement from Colonel Leonard

General Meade was the 4th change of command in the Army of the Potomac within the previous 8 months. Some of the Army fought at Gettysburg without knowing of this change.

Sunday, June 28.

Marched over the mountain to

Frederick City, a distance of ten miles. These familiar

scenes raised the spirits of the regiment very high, and the old war

songs were sung with a fervor we hadn’t felt for a long time.

The colonel announced to the regiment that General Meade was to take command of the Army of the Potomac in place of General Hooker, removed; adding, jocosely, “that we needn’t be discouraged, as we all might yet receive the same honor.”

At the 150th Anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg, noted historian Ethan Rafuse, gave a talk covered by C-Span. The history of each corps, and corps commanders assembled by General Hooker, inherited by General Meade when he assumed command, was discussed. Politics was king in the Army of the Potomac. The following is created from the notes I took while watching.

General George B. McClellan organized the Army of the Potomac in the Spring of 1862. Its 8 corps commander assignments needed to be approved by the government administration. President Lincoln didn’t like General McClellan’s military plans (bringing the army to the Lower Chesapeake to confront the Confederates) so he appointed 4 men (of the 8 commanders) that also objected to McClellan’s plan.1 Politically this is significant. Who is a corps commander loyal to? Answer: They are loyal to the person that appointed them to command. In essence General McClellan was being watched by the Lincoln Administration, something that would obviously contribute to the break down in confidence between the commander and the president. Politics continued to play a role in the high command throughout the war. Here is the history of the various corps and the team General Hooker assembled when he was in command of the Army of the Potomac..

First

Corps. The 1st

Corps was organized in March, 1862, under General Irvin

McDowell.

It became the 3rd Corps commanded

by McDowell in John Pope’s little “Army of Virginia.” It was

not a part of General McClellan’s Army

of the Potomac. The loyalties of its men and officers was

neutral. The 13th Mass. were in this

organization. When General McClellan

resumed command of the Army in September, 1862, the First Corps joined

the rest

of McClellan’s Army of the Potomac. General Hooker was

assigned its command, and

it fought well under his leadership at Antietam.

Major-General John Fulton Reynolds commanded the

corps after Hooker. A graduate of West Point Military

Academy,

Reynolds was universally held in high regard, though Ethan said there

is no direct

evidence to justify this high regard.

Reynolds did little fighting at Chancellorsville.

At Fredericksburg

he came up short when General Meade requested re-enforcements for his

bloodied

division as it was falling back.

Second Corps. The 2nd Corps was organized in March, 1862, under the command of General Edwin ‘Bull’ Sumner. He had decades of service on the plains and in Kansas but was lacking the qualities needed to manage a corps. This was one of McClellan’s prime units. When Sumner left the army, West Point graduate, General Darious Couch stepped up to take command. Couch had a reputation as a McClellan supporter, and was critical of Hooker’s leadership at the Battle of Chancellorsville. After that, he refused to serve under him. General Winfield Scott Hancock replaced Couch as commander of the 2nd Corps. [General Hancock, pictured, right.]

General Couch was appointed commander the Pennsylvania Militia by President Lincoln during the crisis of Lee’s 2nd Northern invasion.

Third

Corps.

This corps was originally commanded by another military academy

graduate, General

Samuel

P. Heintzleman. This organization

was General Hooker’s original

military home. He commanded a brigade then the 2nd

Division under Heintzleman, who was critical of Hooker.

Wikipedia states Heintzleman’s popularity was

eclipsed by his younger, more aggressive division commanders, Joe

Hooker and

Philip Kearny. In late 1862, Heintzleman

was assigned to the defense of Washington. When General

Hooker assumed command of the

Army of the Potomac he appointed Major-General

Daniel Sickles to command the corps.

Sickles was not a West-Pointer.

His loyalty was to General Hooker.

Sickles fought well at Chancellorsville in spite of Hooker’s poor

leadership and Hooker's decision to abandon Hazel

Grove, the strategic high ground that Sickles held at

Chancellorsville.

General Sickles, [pictured,

left] would have friction with General Meade at Gettysburg.

Fifth

Corps. Formed

in May, 1862, command was given Major-General Fitz John

Porter.

Porter was another graduate of the United States Military

Academy at West Point and a young protégé of General

McClellan. He was

however,

wrongly made the political scape-goat of General John Pope after the

disastrous

defeat of Pope’s army at 2nd

Bull Run.

The corps was commanded by Major-General

Daniel Butterfield at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville.

Butterfield was not a West Pointer, and was a close ally of General

Hooker, and served as Hooker’s Chief of Staff.

He staid on as Chief of Staff to serve General Meade, during the

Gettysburg Campaign. General George Sykes [pictured] commanded

the

corps in the field.

Sixth Corps. General McClellan organized the 6th Corps in March, 1862, with General William B. Franklin in command. After Burnside's tenure as commander of the Army, General Franklin was replaced by General John Sedgewick, another military academy graduate. At the battle of Antietam Sedgwick’s Division (II Corps) suffered severe casualties in a brutal fight. Consequently he became a cautious leader. [General John Sedgwick, pictured, left.]

Eleventh

Corps. The 11th

Corps was originally a unit commanded by General John C. Fremont in

1862. Fremont

resigned when the Army of Virginia was organized under General John

Pope. The unit became the first corps of Pope’s

little army with General Franz Sigel commanding. Following

Pope’s defeat at 2nd

Bull Run the corps was incorporated into the Army of the Potomac

as the 11th Corps. General

Sigel resigned in February, 1863, and replaced by General Oliver O.

Howard. Howard lost his right arm while

brigade commander at the Battle of Fair Oaks,

June, 1862, with McClellan on the Peninsula. The corps

consisted mostly of German troops

who had an affinity for Sigel and were resentful of

Howard. At

Chancellorsville

the corps bore the brunt of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson’s

famous

flank attack and earned a bad reputation for breaking in

battle.

Howard was a religious man, an abolitionist,

a teetotaler and generally unpopular.

General Hooker did not like Howard and blamed him for the

defeat at

Chancellorsville. [General Oliver O. Howard, pictured, right.]

Twelfth

Corps.

Originally in command of Major-General N.P. Banks in the Department of

the Shenandoah, the unit also became part of John Pope’s Army of

Virginia (2nd

Corps) in June 1862. As it was another unit that

was not originally part of the Army of the Potomac,

its loyalties were independent of those politics. General

Joseph K. Mansfield briefly commanded

the corps before his death in battle at Antietam. General

Henry Slocum commanded the corps in

October, 1862. Slocum came up under General William B.

Franklin in the

Peninsula campaign where he distinguished himself. General

Slocum [pictured, left]

was

vocal in calling for Hooker’s

removal after the Battle of Chancellorsville.

The Cavalry Corps was commanded by General Alfred Pleasonton. Hooker had organized the Union Cavalry into its own corps to be more effective. Pleasonton replaced General George Stoneman after the Chancellorsville Campaign. Under Hooker the Union Cavalry learned its job and proved itself. The Confederate Cavalry, long unopposed now had a formidable adversary. [General Alfred Pleasonton, pictured, right.]

NOTES: 1. The 4 Corps Commanders Lincoln appointed were Irvin McDowell, Edwin Sumner, Samuel Heintzelman, and Erasmus Keyes. Keyes supported McClellan's plans “but joined those who insisted the lower Potomac be cleared first.” From "McClellan's War, by Ethan S. Rafuse, Indiana University Press; 2005, pages 191 - 192.

"Bread and Tears"

Excerpts of Sam Webster's diary (HM 48531) are used with permission from The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA.

Being in familiar territory, some of the men were tempted to drop out of line to visit friends made the previous year. Savvy drummer Sam Webster, a native of Martinsburg, Va., was pretty good at the game as his diary attests. The same behavior had more serious consequences for color sergeant Roland B. Morris, as the court-martial at the end of this page shows.

Friday, June 26th,

Brigade had

right of corps, and so we had a hurried march to catch it.

Through Barnesville and Adamstown (on Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road) and

over the Catoctin mountains to Jefferson. Camp. As

we came

through Adamstown someone had a dinner ready for Ike and I, but we

didn’t get it. Got a lot of cherries,

however. Saw

Bob

Herring at a butcher shop in Jefferson. Got out on the

Burkettsville pike to Centreville, and would not have gotten back had

it not been for an officer’s cook of the 1st Division, who had a pass,

and got me thro the piquet with him, coming back at night.

Nice country

– but have no money to buy anything.

Saturday,

June 27th,

March

to and a mile or so beyond Middletown, at which place we find the 11th

Corps. The 94th N.Y. which was detached at White Oak, rejoins

us;

but is put in 2nd Brigade. Went out a mile or two to a little

village called Beallsville, and got some milk, soft bread, and apple

sauce.  Borrowed the money, trusting to get it out of

Sawyer,

who

promptly paid it. [Sam's

friend, drum-major Appleton Sawyer, pictured.]

He’s got a

little bit left. Joe

Kelly and

some more of the fellows got as far as Myersville, a mile

further. Found a man with a 50 cent sutler’s check

he had had

put

on him for produce while we laid at Antietam last fall. He

gave

it to one of them, saying he “couldn’t pass it nowheres.”

Borrowed the money, trusting to get it out of

Sawyer,

who

promptly paid it. [Sam's

friend, drum-major Appleton Sawyer, pictured.]

He’s got a

little bit left. Joe

Kelly and

some more of the fellows got as far as Myersville, a mile

further. Found a man with a 50 cent sutler’s check

he had had

put

on him for produce while we laid at Antietam last fall. He

gave

it to one of them, saying he “couldn’t pass it nowheres.”

Sunday, June 28th,

Went

over the hills with Libby to Mr. Mains (90 years old.)

Chatted

with his granddaughter, and ate cherries. Returning to camp

found

the Brigade gone, my knapsack packed, and a note stating the

route. Caught up in a short time and marched over

the

mountain, by the old pike, to Frederick County

Almshouse. Had

a

great deal of fun about a fence that we ultimately used for

firewood.

Monday, June 29th,

Crossed

to Emmitsburg pike, passing through Mechanicsville, and camping about

a mile beyond Emmittsburg, on the Fairfield road. Emmitsburg

is

about half burnt. Great deal of jocosity on the part of the

boys

at the expense of the Principal and students of Mount St.

Mary’s

College and considerable laughter at the Emmitsburg people, who

greeted every mounted officer with: “Three cheers for the

General,” even were he a 2nd Lieutenant. Much rain

in the

morning.

The Last Letter of Charles Leland, Company B

A researcher in Walpole, Mass., wrote me, that Leland, originally from Chelsea, Mass., joined the 13th., in 1861 with several school mates from his grammar school days in Chelsea, who all went into the service together. Charles was 16 years old at the time and enlisted with his father’s permission.

Twenty year old Edwin Field is definitely one of these friends. Who the others were is speculation, but Charles mentions the following company B boys in letters to his father; Walter P. Beaumont, Loring Bigelow, and William L. G. Clark.

Corporal

George Worcester, age

22, was friends with Leland’s father, a

fellow mason, and took it upon himself to look after young

Charles. In February, 1862 George wrote to Leland's father:

Corporal

George Worcester, age

22, was friends with Leland’s father, a

fellow mason, and took it upon himself to look after young

Charles. In February, 1862 George wrote to Leland's father:

“I had been anticipating a letter from you for some time, that which you wrote concerning the commission…I hope… that I shall through your influence obtain it. …as for your son he is better able than half the men that have received a commission the only thing that would be against him would be his age …he does not use any intoxicating drink…I have kept a strict watch over him. “ [Feb 13, 1862.]

In March, 1863 Sergeant Worcester wrote Charles' father:

“Last week, I saw Lt [Morton] Tower, of Co. B… I asked as a special favor a corporals warrant for your son, which he promised to give him. I have every confidence in Lieut. Tower, it will be a small promotion, but it gives him just one step above the privates… he will be in direct line of promotion and I hope he will be more successful than I have been. If he wants it you could procure him a commission in one of the negro regts. Quite a number of the boys accepted such a commission… he would only have to procure a recommendation from Col Leonard and have it presented to Governor Andrew with the understanding that he wishes the commission in a colored regiment… better men than I have gone from the regiment to accept such commissions.” [March 23, 1863.]*

George Worcester received a Lieutenants commission in the 3rd Massachusetts Heavy Artillery in April, 1863. There was not enough time for Leland to be appointed Corporal, he and his friend Edwin Field were killed at Gettysburg.

From time to time Leland’s letters come up for auction on various websites. Also, the Pearce museum in Navarro, Texas has several of Charles’ letters in their collection. I obtained permission to post two of them on this website, but they preferred I only summarize the rest. The following summary complies with this request.

Letter of Charles Leland, June 23rd, 1863, (summary)

Charles

wrote home to his father and presumed his

family knew by now from the newspapers the details of Hooker's

'retreat'

toward Washington and about the Rebel raid into Pennsylvania.

It

was

Leland's thought the rebs were trying to lure Hooker into Maryland so

they could turn and attack Washington.

Charles

wrote home to his father and presumed his

family knew by now from the newspapers the details of Hooker's

'retreat'

toward Washington and about the Rebel raid into Pennsylvania.

It

was

Leland's thought the rebs were trying to lure Hooker into Maryland so

they could turn and attack Washington.

It is interesting to note the way events appeared to contemporaries during the war. Hooker's move north to counter Lee's army was viewed as a 'retreat.' There was still a great deal of importance put on ground gained or lost in a battle regardless of the strategic results as far as bringing the war to an end. Charles wrote:

"Hooker has got his forces situated all along on the creeks from Leesburg to Aldie, and facing the Blue Ridge. Our Corps is situated on a stream called Broad Run, about eight miles from Leesburg and three from the Potomac in Loudon County-Va.

They had a cavalry and Infantry fight at Aldie yesterday and we drove the rebels back three or four miles."

Like many others in the ranks, Charles believed Lee's army was bigger than Hooker's. Directly after the battle of Chancellorsville, thousands of '2 years' volunteers departed for home, their term of service had expired. This greatly weakened the Army of the Potomac. The reality however, was the opposing forces were relatively equal in strength. But Hooker believed he was outnumbered and that belief transmitted to the rank and file.

Charles expressed the opinion Hooker would have to act defensively until the army was strengthened by conscripts, from the newly implemented Federal draft laws. He then comments about the commendable performance of negro regiments at Port Hudson. He was echoing the newspaper opinions when the tenacious performance of the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards proved their worth. The National Park service states on their website:

"The assault on Port Hudson offered them the first opportunity to demonstrate to all witnesses that the black race could match any white troops in prowess on the battlefield. ...The Battle of Port Hudson marked a turning point in attitudes toward the use of black soldiers." -NPS

Before closing Charles tells his father, "You might send me those books any time as I can read them now as well as at any time."

Letter of Charles Leland, June 29th, 1863

A private collector is carefully preserving several of Charles' letters and has generously shared them with me for use on this site. Charles wrote the following letter the morning of June 29th, before the 26 mile march to Emmitsburg, in the rain.

In camp at Middletown, Md., June 29th 1863

Dear Father,

I am well after a long and hard march, and we are at last in Maryland. Things look now as if we were going up Pennsylvania and meet the rebels somewhere in the Cumberland Valley. The main request I have to ask is for a little money as I am all out and we are in a country where if we have a little money we can live high. To get in from a long march and have something where with to get some bread is a great consolation to a hungry soldier. The prices are as low for bread as they are in Massachusetts being 25 cents for very large loaves. I write this fast before we start in hopes I can mail it in some of the towns on the march on our way, and then you could send me some right off.

There is to be some stirring news before long from our army.

Please send me five or ten dollars as soon as possible in greenbacks, and oblige your affectionate son. Chas. E. Leland.

I would write more if I had time. Love to Henry, Ada, Mother and yourself.

I expect we have got some hard marching to do, although we can not march harder than we have done.

A post script at the bottom of the letter, reads, in full: "This is the last letter Elwin ever wrote us as he met the rebels on the 1st of July and gave his life for his country."

Sergeant John Boudwin's diary records the following for the march to Emmitsburg.

June, Sunday, 28. 1863

Left camp at Middletown at 2 P.M. - had regimental

Inspection in the morning - Marched to Frederick City and camped for

the night - received mail and letter from Libie and some papers from

Mrs. Moriarty- arrived in Fredrick at 8 P.M. wrote letters to mother

and wife.

June, Monday 29. l863

Came in with rain - Revillie at 3 A.M.

cooked Breakfast and started at 4 l/2. Passed several small

towns on the march. Mechanicstown the women were crying and

they treated us very kindly giving us Bread and Pies Cakes

&c. I had not seen so much crying since I left Boston

-

arrived at Emmittsburg at 5 P.M. having marched us the

distance of 26 miles and it was done in 12 hours - for l0 miles the mud

was inches deep. The town is quite a large one

their is a large Catholic College and a Female Seminary - we did not

want for anything had bread and cakes and plenty of

cool water camped for the night out side the Town - feel very

tired and used up. Took several prisoners as we arrived

outside the town.

Monday, June 29.

We made a forced march of twenty-six

miles to Emmitsburg,

passing through the town and camping about a mile beyond, on the

Fairfax road. It rained all day, and many of the men were

obliged to march barefoot for want of shoes.

The inhabitants brought to the roadside bread, milk, cheese, and other eatables, which they freely dispensed to us as we passed along. To be the recipients of such kindness from the people had a great effect in enlivening the spirits of the boys.

While halting at Mechanicsville, a farmer and his wife were seated in a wagon loaded with bread which they tossed to the hungry soldiers, his wife sobbing and bemoaning the terrible fate that awaited us.

“Oh boys, you don’t know what’s before you. I’m afraid many of ye’ll be dead or mangled soon, for Lee’s whole army is ahead of ye and there’ll be terrible fighting.”

One of our officers jumped on to the wagon to help the farmer, shouting, “Walk up, boys, and get your ration! Bread and tears, tears and bread,” while he tossed the loaves about. “Who takes another ?”

The boys, undismayed by the old lady’s prophetic words, shouted their thanks, with “God bless you, old lady!” and rousing cheers for the old gentleman.

The people in the town of Emmitsburg were jubilant at sight of the troops, whom they greeted with great cordiality. Without regard to rank, everybody on horseback was greeted with “Three cheers for the ‘general’ !” which were given with a will.

"You Have Insulted Ze Gener-al"

General Abercrombie called them impertinent, General Hartsuff called them saucy, General McDowell said they were a bandbox brigade, they called themselves 'spirited.'

Charles Davis, Jr.'s narrative continues; from "Three Years in the Army," pages 221-223.

There was an irrepressible

spirit of levity in the Thirteenth,

and presumably in other regiments, as there is no patent on the animal

spirits of young men. If there was any fun to be had, it was

soon found. Toward the last of our service it was hard

pickings, but still there was some one to excite laughter by a quaint

saying, an apt nickname, or innocent joke, to relieve the strain and

monotony of our daily lives. We were just as likely to get

our fun out of a major-general as we were out of ourselves.

The dignity and importance that hedged a general never affected us in

the least. Every opportunity to ridicule or

criticise the

doings of an officer outside the regiment was taken advantage of by the

wits and the growlers, to excite mirth or ridicule. We were

never quite satisfied with ourselves if we failed in fastening a

nickname on a general officer, particularly if he was a martinet, or if

he presented some peculiarity of manner or dress that suggested a

name. One officer was called “Old Crummy,”

another “Butter and Cheese,” another the

“Apostle,” and still another “Old

Bowells.” Nicknames were so common among ourselves

that few

of the boys escaped without one.

There was an irrepressible

spirit of levity in the Thirteenth,

and presumably in other regiments, as there is no patent on the animal

spirits of young men. If there was any fun to be had, it was

soon found. Toward the last of our service it was hard

pickings, but still there was some one to excite laughter by a quaint

saying, an apt nickname, or innocent joke, to relieve the strain and

monotony of our daily lives. We were just as likely to get

our fun out of a major-general as we were out of ourselves.

The dignity and importance that hedged a general never affected us in

the least. Every opportunity to ridicule or

criticise the

doings of an officer outside the regiment was taken advantage of by the

wits and the growlers, to excite mirth or ridicule. We were

never quite satisfied with ourselves if we failed in fastening a

nickname on a general officer, particularly if he was a martinet, or if

he presented some peculiarity of manner or dress that suggested a

name. One officer was called “Old Crummy,”

another “Butter and Cheese,” another the

“Apostle,” and still another “Old

Bowells.” Nicknames were so common among ourselves

that few

of the boys escaped without one.

Pictured above, (far left) is General George Lucas Hartsuff, who liked the '13th Mass,' but claimed they were the 'sauciest' set of men he ever saw. 8-18-62 Boston Evening Transcript.

Just as soon as a lot of boys

discover that a man takes notice

of their gibes the fun begins. You might as well stir up a

hornets’ nest as to notice the remarks of young boys, as every sensible

person knows. We had no intention of being insubordinate, yet

our conversation was often loud enough to be heard by a passing

officer, as happened to-day on our march to Emmitsburg, while

General Robinson and his staff were sitting on a piazza taking a rest

as we went by.

Just as soon as a lot of boys

discover that a man takes notice

of their gibes the fun begins. You might as well stir up a

hornets’ nest as to notice the remarks of young boys, as every sensible

person knows. We had no intention of being insubordinate, yet

our conversation was often loud enough to be heard by a passing

officer, as happened to-day on our march to Emmitsburg, while

General Robinson and his staff were sitting on a piazza taking a rest

as we went by.

General John C. Robinson, pictured, left.

There

was no impropriety in

their doing so,

and really nothing to complain of. The boys themselves were

tired out

with days of constant marching, and as we passed the house where these

officers were so comfortably sitting, one of the boys remarked with a

rather loud voice, “How they must suffer!” Shortly

after, one

of the general’s staff approached our colonel and in a very excited

manner said, “Colonel, your men have insulted ze general.”

“My men?”

“Yes, colonel, your men have insulted ze general.”

“In what way?”

“Zay said, ‘How zay must suffer!’”

“Well, don’t they suffer?” said the colonel.

“I will go back and zay that you have insulted ze general.”

General Robinson was too sensible a man to bother with the remarks of tired solders. So long as the men made good time in their marching, he was quite willing they should relieve their feeling, even at his expense, and we never thought any worse of General Robinson, who was an estimable officer, for taking the rest he must have needed.

It was part of our daily life to form and express opinions about matters and persons, and woe betide the officer who was silly enough to notice them. In dealing with children or soldiers, which is the same thing, it doesn’t pay to have your hearing or your eyesight too keen.

Note: General John Abercrombie is 'Old Crummy,' General Rene Paul is 'The Apostle,' and General John C. Robinson was 'Old Reliable.' I believe Colonel P. Stearns Davis of the 39th Mass. Vols. is "Old Bowells." The identity of 'Butter and Cheese' is still unknown to me. - B.F.

Letter of David Sloss - 'Nicknames'

'Davie' Sloss carried the State Colors of the regiment for quite a while, though exact times are not known. He carried them at Gettysburg, and still had them at Spotsylvania, May 8, 1864, when he was slightly wounded. Sloss' descendant still treasures a small piece of the white silk state flag; a souvenir Sloss saved for himself before returning the colors to the Massachusetts State House at the end of service. In 1908, he wrote a letter to his comrades in Boston in which he recalls several 'nicknames' the boys had given each other. In the spirit of the narrative I offer it here. ( If only I knew the identities of his friends ! )

From 13th Regiment Association Circular #22 Dec. 1, 1909.

Chicago, Ill., Dec. 1, 1908.

Dear Comrades of the Old Thirteenth:

The season of the year has come when the "Old Thirteenth Mass." nests again, and counts the fallen in the fight with "Father Time." And not to recognize the fact on my part would be like forgetting all the eventful days I spent with some of the truest men that I have ever met in all my seventy years of life.

Every

time the "Old Thirteenth"

comes up in my mind my thoughts go back to the three years I spent with

you. Never a day off duty, and to-night I am going back to

the

early days of '61 and visit the Maryland towns we passed through that

year : Hagerstown, Williamsport, Middletown, Boonsboro,

Maryland

Heights, Darnestown, Falling Waters, Dam No. 5, Frederick,

Antietam

Creek, and other places.

Every

time the "Old Thirteenth"

comes up in my mind my thoughts go back to the three years I spent with

you. Never a day off duty, and to-night I am going back to

the

early days of '61 and visit the Maryland towns we passed through that

year : Hagerstown, Williamsport, Middletown, Boonsboro,

Maryland

Heights, Darnestown, Falling Waters, Dam No. 5, Frederick,

Antietam

Creek, and other places.

These names bring up some of the pleasant memories, for were we not the "finest" regiment the people had ever seen, and we were not forced to show our "bad side" to them. These were our best days. War had smoothed its wrinkled front and every day was a pleasure.

Our overflowing animal spirits had to have an outlet or we would "bust." Oh, such pranks! Our weak point soon commenced to show, and then the nicknames that some of us got! Can some of you remember "Smooth Bore," "Cockey Robinson," "Doc Square," "Stun," "Lively Jesus," "Whiskers," "Molasses," "The Tape Worm," "The Old He One," "Rockers," "Dip Toast," and "Old Festive." These are a few I can remember or call up from the misty past, and some of the expressions that still stick. You recollect "Gaylord's" first text, "What came ye out for to see, the reed shaken by the wind?"

Stun's "I kacked me piece, and then I hallered." Joe Cary's "Oh, Tom! Cold Tea, Cold Tea, Tom!" Sawtelle's "Come over and have a game of cribbage." Cockey Robinson - "I'll go to McClellan, by God I will." Casey - "How can I shoot with my arm. Lieut.?" Capt. Schreiber - "Doubley-quick Co. I, doubley quick."*

These are some of the

expressions I recall and will perhaps

freshen up some of your memories to recall others.

These are some of the

expressions I recall and will perhaps

freshen up some of your memories to recall others.

In those early days every one had what we now call "an affinity," but in those days it was "Buddy" or "Pard"; men who you would risk your life for. Of course I had one going out, "Jimmy Cullen," who had a little dog called Tim. Jimmy got sick at Maryland Heights, I tried to cure him with fried chicken, but John White caught me and he was discharged. I had lots of "Pards" who did not wear well. Toppy Emerson had one, "Percy Beemis," a nice little man, quiet; he disappeared at Rappahannock Junction;* we hunted for him a few days, as far as Pennsylvania, but did not find him. I received a paper from home with the item in it, "A man registered at a hotel in Montreal as Percy Beemis had committed suicide." Toppy told me the story of him, going to Boston and his sweetheart would have nothing to do with him, and his brother sent him to Canada. This was our first deserter, although I saw another in Poughkeepsie, George Dean.

While at Darnestown as Provo, I was on guard at a tent one night in which was a man with ball and chain reading his beads by the light of a lantern; his name was Lannigan, he had killed his Major in the Forty-sixth Pennsylvania and was going to be hanged the next day; we came away, however, before he was hanged.

Now, comrades, I have jotted down some of the reminiscences of "Old Dave Sloss," not "Old Joe Clash," as Jim Fish used to say.

We have a bully four out here, composed of Pierce, Curtis, Prince, and myself. We had the pleasure of a visit by W. H. H. Howe, of Boston, on the 17th of September and made a day of it at Pierce's home.

David Sloss

NOTE: An article in the Westboro Transcript about the suicide of Percy Bemis is on the 'Darnestown' page of this website. See site map page.

"We Express Hope the New Commander will Show More Ability than His Predecessors"

Situation June 30th, 1863.

Situation June 30th, 1863.

This map shows the situation on June 30th 1863. General Lee learned the Union army was in Maryland, near Frederick on June 28th and wanted to concentrate his forces. Richard Ewell's Corps was at Carlisle, and planning to invest the capitol city of Harrisburg on June 29th when he received Lee's orders to change direction and march toward Chambersburg. One of Ewell's divisions was well under way on June 29th when Lee's orders were revised, instructing Ewell to march toward Heidlersburg, near Gettysburg. Two of his divisions camped there on June 30th. The division that had already marched arrived at Fayetteville near Chambersburg.

General A.P. Hill's Confederate 3rd corps is at Cashtown, Pa, 8 miles west of Gettysburg. A detachment of two Mississippi regiments with artillery support have been posted at Fairfield near Emmitsburg, (not indicated on this map.) Two Divisions of General Longstreet's 1st corps are at Greenwood, east of Chambersburg where the wagons and reserves are located.

General J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry has tangled up with General

Kilpatrick's

Division at Hanover, Pennsylvania. Stuart is trying to return

to Lee's main army and sneaks away at night.

John Buford's Union cavalry has arrived at Gettysburg. The Union First Corps is camped 5 miles south of Gettysburg near the Marsh Creek Bridge. The 11th Corps is protecting approaches to Emmitsburg, from Fairfield, Pa., and Frederick, Md. The 3rd Corps is between Bridgeport, Md. and Emmitsburg within supporting distance of the 1st and 11th Corps. The 5th Corps is at Littlestown, Md., the 6th Corps is at Manchester. General Meade's Headquarters is at Taneytown, centrally located to the wings of his army.

The Union troops at Carlisle, Harrisburg, and Columbia, are General Couch's mostly unreliable troops of the emergency militia.

Excerpts of Sam Webster's diary (HM 48531) are used with permission from The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. Sam Webster's comment that a number of the boys were tight is interesting....

Charles

Reed sketch, - 'Applejack.'

Charles

Reed sketch, - 'Applejack.'

Tuesday, June 30th,

1863

Marched back through

Emmitsburg, and

out two or more miles

on the Gettysburg

road. Borrowed

$5.00 of Lt. Washburn.

Posted off a couple of miles towards Fairfield

road, and got some bread, butter, and milk.

Found a number of the boys tight owing to the nearness of

a

distillery. Pitch

tent just in time to

escape a hard shower. Passing

through Emmittsburg,

some one recognized me and called out, “There goes Sam Webster."

Thought it was one of the

boys, and when

certain it was otherwise, went back but couldn’t find her.

(Knew, afterward, that she

was from

Westminster.)

Sergeant John Boudwin's diary concludes this series of difficult marches with the following entry for June 30th.

June,

Tuesday, 30. 1863

Came in with Rain Left

camp at Emmittsburg and Marched out to

the left of the Town and camped near Mill Brook awaiting orders to

march. laid here

all day went down to creek and had

a Bath

went to bed early- and had

a good nights

rest. Nothing

occurred during the day or

eve.

Charles Davis Jr.'s narrative continues; from "Three Years in the Army,"

Tuesday June 30.

About 10 A.M. we marched back through

Emmitsburg, meeting the

Eleventh Corps on our way, which caused us a good deal of

delay. We passed through the town out upon the Gettysburg

road about two miles, near Marsh Creek, where we halted and stacked

arms, it being asserted that the enemy was between us and Gettysburg.

It having rained every day except Sunday since we crossed the river, the roads were consequently very muddy.

The Eleventh Corps had been keeping along with us, but the remainder of the army we had not seen. We enjoyed the marching very much, in spite of our fatigue. Day after day we were met on the way by women in front of their homes with pails of fresh water, milk, bread, cake, and pies, which they freely distributed among us.

The following order by General Meade was this day read to the army:

The enemy are upon our soil. The whole country now looks anxiously to this army to deliver it from the presence of the foe. Our failure to do so will leave us no such welcome as the swelling of millions of hearts with pride and joy at our success would give to every soldier of this army. Homes, firesides, and domestic altars are involved.

Corps commanders are authorized to order the instant death of any soldier who fails in his duty at this hour.

If there was any man in the army who remained unaffected by the words of confidence and reliance that had been showered upon us by the loyal people of Maryland, whose generous hospitality had met us at every turn of the road, perhaps the closing paragraph of this order might arouse his sluggish nature to duty. The fact is that the soldiers of the Army of the Potomac needed no incentive of this kind; it had fought desperately before, when success would have been achieved if the skill of its commanders had been equal to the valor of the men.

When we were dismissed, the merits of this circular were freely discussed, and the boys were pretty generally of the opinion that the sting conveyed in the closing paragraph was undeserved and unnecessary to an army with a record for fighting such as the Army of the Potomac had won. Later on, the boys thought it would be rather a good idea for the rank and file to issue a manifesto to the commander, expressing the hope that he would show more ability and judgment than his predecessors had shown when conducting a great battle, and above all, avoid issuing appeals or circulars reflecting the slightest doubt on the courage of the men. “Nelson expects every man to do his duty!” were the only words of that great commander to his men, and they did their duty and did it nobly. It is often within the power of a commander to inspire his men to great deeds by words of confidence in their courage and ability, - not by intimidation.

The First Corps was composed, like other corps, of three divisions; each division taking its turn in marching at the head of the column, as brigades also do in their respective divisions.

The First, Third, and Fifth Corps were under the immediate command of General Reynolds. The first was at Marsh Creek, the Eleventh at Emmitsburg, and the Third at Taneytown, under orders to relieve the Eleventh Corps at Emmitsburg.

Emmitsburg, Before the Battle of Gettysburg

Historian John A. Miller, a cyber-friend of mine has written a series of wonderful articles, among many other wonderful articles at the Emmitsburg Area Historical Society. [www.emmitsburg.net] I have requested permission to reprint it here. I strongly recommend my readers visit the Emmitsburg website for more history.

Emmitsburg,

150 Years Ago, Before the Battle of Gettysburg

by John Miller

Emmitsburg Area

Historical Society

This year [2013] marks the 150th Commemoration of the Battle of Gettysburg and the Pennsylvania Campaign. During the time period, 150 years ago, Emmitsburg residents saw first hand, thousands of Union soldiers enter and occupy the grounds surrounding the town. From the west to the north, thousands of Union soldiers encamped here before heading into battle. Those soldiers were veterans and accustomed to long marches in the heat of the sun, or during heavy downpours of rain. Life was not easy for the Civil War soldier. But they bore it for their cause and their beliefs, with the help of their messmates.

Life for the average Emmitsburg resident was not easy either. Just like the Civil War soldier they endured hardships of their own. By the time the first Union soldier entered into their community, many residents were displaced from the "Great Fire" that erupted during the night of June 15th. For many of those residents, they lost everything that they had. Within a week and a half, they would endure more hardships, as thousands of Union soldiers would come to occupy the fields surrounding the town.

On June 27th, 1863, Dr. Thomas Moore from Mt. Saint Mary’s College recalled seeing the first soldiers in blue marching pass the college and head for Emmitsburg. Among the soldiers he saw were the 5th and the 6th Michigan Cavalry. "They jogged along, four abreast, many of the weary riders leaning forward, sound asleep on the necks of their horses. Many of us sat on the fences along the road watching and listening to their sayings. We naturally looked upon the men as sheep led to the slaughter, and we were not a little surprised when we overheard two of them closing a bargain on horseback with the remark: 'Well, I will settle with you for this after the battle. Will that suit you?' The other party readily assented. The whole period of life is treated as a certainty, even by men going into battle."

These riders were part of General Joseph Copeland’s Michigan Brigade that was now under the command of a young general, General George Armstrong Custer. They encamped on the grounds of St. Joseph’s. The young general Custer would greet his command at Emmitsburg, and hired local resident James McClough to guide his brigade.

Pictured

are some of the large buildings at St. Mary's College,

Emmitsburg.

The photo is credited to Timothy O'Sullivan, 1863.

Pictured

are some of the large buildings at St. Mary's College,

Emmitsburg.

The photo is credited to Timothy O'Sullivan, 1863.

The next day, more Union soldiers came into town on horseback. These men were part of the Keystone Rangers, Company C of Cole’s Cavalry. Many of these men were from Emmitsburg. They had with them several Confederate prisoners. The next day, these men were escorted to Frederick, Maryland.

During the evening of June 29th, General John Reynolds, commanding the left wing of the Army of the Potomac entered Emmitsburg after a hard march from Frederick. The weary soldiers of the First Corps encamped in the fields surrounding St. Joseph’s, stretching toward the Emmit House. Following along another road was the Eleventh Corps, and they would encamp southwest of Emmitsburg, closer to Mt. Saint Mary’s College.

As the evening went on, a practical joker quietly spread a rumor that Mother Superior had invited all of the commissioned officers to a reception, with suitable refreshments, to be held in the main building of the institution. Some of the men actually believed what they heard, and once arriving at the convent, they were quickly surprised to see that it was in total darkness.

A.J. Brown, who recorded his experiences of seeing the Union soldiers wrote: "We were visited by single soldiers, officers, groups, etc., to the amount of some thousands, some for the purpose of seeing old friends and companions."

Upon seeing the St. Joseph’s convent, Corporal Adam Muenzenberger of the 26th Wisconsin recalled his experience at Emmitsburg. "We must march like dogs and now that the rainy weather has started the road is pretty bad. We camped a few days at Middleton and then we proceeded to Frederick City. We camped there over night and the next day we marched to Emmitsburg. There we camped on a wet field and this morning we marched two miles nearer the hills where the St. Joseph's convent is located. We have our camp close beside the convent. Should we stay here for a while - which I doubt - I will receive communion."

Many descriptions regarding the landscape surrounding Emmitsburg were noted by the Union soldiers. Isaac Hall of the 97th New York Infantry recalled: "The broad and smooth road along which they were marching led through a grove, with noble overhanging trees, fresh with large foliage of early summer, and looking through this vista, down a gentle slope, was seen in front the neat and quiet town in the distance. It was a little before sunset, and the weather delightfully serene and mild. The surrounding country had felt none of the miseries of war, and the eager crowds which flocked to the roadside gave evidence in their manner, that troops on the march were a rare spectacle in that region."

Pictured, The Old Emmitsburg Road leading to Mount Saint Mary's College, circa 1880, Emmitsburg Historical Society. The House on the left was called 'Buena Vista.'

Lieutenant William Ballentine of the 82nd Ohio Infantry wrote, "This institution of the Sisters of Charity (whose grounds we are now on) Farm and Buildings (especially the latter) is the finest I ever saw. Nothing in Ohio will compare with it; I was astonished to find such magnificence in such a place, a place I have never heard of before."

There are several accounts of Emmitsburg as it appeared by the Union soldiers. Upon seeing the burned out buildings in Emmitsburg after the fire, William Henry Locke, the Chaplain of the 11th Pennsylvania Infantry noted, "One week ago, the finest half of the town was destroyed by fire, certainly the work of an incendiary but whether a rebel spy, or a home of a rebel sympathizer, does not yet appear."

A View of Emmitsburg, June, 1863 following the great fire of June 15th; Emmitsburg Area Historical Society

Major Frederick Winkler served in the 26th Wisconsin Infantry and on General Schurz’s staff recalled, "A large portion of the place is in ruins, having been destroyed by fire; expensive buildings of the Catholic Church, convents, etc., occupy very fine grounds on the limits of the place; not far from here too, at the foot of the mountains, there is Saint Mary's College, said to be the oldest college in the country."

Lieutenant William Ballentine of the 82nd Ohio Infantry recalled "About one half of the town was burnt about two weeks ago. The people think it was done by a resident of the town whom they now have in jail. He is said to be a union man although the town is one of the worst secessionist towns in Maryland. But that was not the reason it was burnt. It was in revenge for some private wrong done by some individual of the town. His store was set on fire and burnt the rest with it."

The next day, June 30th, Dr. Moore recalled, "The Army of the Potomac was truly a beautiful sight" and describes a grand but horrible passing of "the wagons, ambulances, cannons, etc, which were coming early dawn till nightfall. ... They camped around Emmitsburg. Their campfires, as viewed from the college windows, almost led one to imagine that this section for miles had received in one shower all the stars of the heavens."

Pictured below, is a view of the surrounding countryside from behind St. Mary's Seminary.

General John Reynolds ordered the First Corps to march to Marsh Creek, located to the north of Emmitsburg, in Pennsylvania. A soldier of the 121st Pennsylvania Volunteers recalled marching through town. They were greeted by cheering townspeople who waved handkerchiefs, flags, passed out water, cakes and bread. "The commissary wagons were unable to keep anywhere near the troops on this march, and, as a consequence the want of food induced many of the men to leave the ranks and raid on the products of the farms of this rich country."

The young boys of Emmitsburg were excited at seeing the soldiers go marching by. Members of the 12th Massachusetts Volunteers recorded a story about a courageous boy who wanted to be a soldier "An instance of the bravery of a 15 year old Emmitsburg lad named J. W. (C.F.) Wheatley, as Baxter’s brigade was marching through Emmitsburg it was followed by the village boys, one of whom continued to the camp at Marsh Creek, where he offered to enlist. His offer, however, was ridiculed, and he was sent away. On the morning of the 1st of July he reappeared, and so earnestly entreated the Colonel of the Twelfth Massachusetts to be allowed to join his regiment, which a captain of one of the companies (Company A) was instructed to take him on trial for a day or two. When the regiment halted near the seminary, the boy was hastily dressed in a suit of blue."

"Afterwards, during the action [at Gettysburg], he fought bravely until a bullet striking his musket split it in two pieces, one of which lodged in his left hand and the other in his left thigh. The boy was taken to the brick church in the town to be cared for, but nothing was afterwards seen or heard of him until July 4th. I saw him for the last time bitterly crying for his mother and sundry of other relatives. He was never mustered into the service, therefore fought as a civilian."

Portions of the Eleventh Corps moved closer to Emmitsburg. During the same time, a division, under the command of General David B. Birney of the Third Corps, was marching in from the direction of Taneytown. They were ordered to Emmitsburg and began occupying the grounds near St. Joseph’s. Colonel Philippe Régis Denis de Keredern de Trobriand wrote about his brief stay at St. Joseph’s. "It was on the domain of St. Joseph that I had placed my brigade. A small stream made part of the boundary line. I leave it to you to guess if the good sisters were not excited, on seeing the guns moving along under their windows and the regiments, bristling with bayonets, spreading out through their orchards. Nothing like it had ever troubled the calm of this holy retreat. When I arrived at a gallop in front of the principal door, the doorkeeper, who had ventured a few steps outside, completely lost her head. In her fright, she came near being trampled under foot by the horses of my staff, which she must have taken for the horses of the Apocalypse, if, indeed, there are any horses in the Apocalypse, of which I am not sure."

Pictured is Saint Joseph's College and Chapel, run by the Sisters of Charity. Photo credited to Timothy O'Sullivan, 1863.

As Colonel Trobriand entered into the building he noted "We reached the belfry by a narrow and winding staircase. I went first. At the noise of my boots sounding on the steps, a rustling of dresses and murmuring of voices were heard above my head. There were eight or ten young nuns, who had mounted up there to enjoy the extraordinary spectacle of guns in battery, of stacked muskets, of sentinels walking back and forth with their arms in hand, of soldiers making coffee in the gardens, of horses, ready, saddled, eating their oats under the apple trees; all things of which they had not the least idea. We had cut off their retreat, and they were crowded against the windows, like frightened birds, asking Heaven to send them wings with which to fly away."

As those soldiers bedded down for the night, they could only imagine what was to come the next day. As dawn came on July 1st, no one in the town of Emmitsburg would imagine that a major battle was going to take place at a small country town called Gettysburg, ten miles to the north. As the day wore on, the sounds of musketry and cannon could be heard. As the Eleventh Corps moved out and headed toward Gettysburg, the rest of the Union Third Corps entered town. There, General Daniel Sickles would halt his Corps for a few hours.

After several dispatches came for General Sickles, he began to march toward Gettysburg, leaving behind one brigade of infantry and a battery of artillery. And just like thousands of soldiers before them, they too were ordered to Gettysburg to fight one of the greatest battles of the Civil War.

Color Sergeant Roland B. Morris

The story of Color Sergeant Roland B. Morris's dramatic death at Gettysburg was another one of the significant moments in the chronicles of the '13th Mass.' He was court-martialled just before the battle, for leaving the ranks without permission, while on the march in Maryland. He had gone, to visit friends he made the previous year when the regiment was camped in the region. At the time he carried the national color of the regiment, so Colonel Leonard took the privilege away from him. On the morning of July 1st, he pleaded with Colonel to restore to him the honor of carrying the colors which was done. He was very cheerful on the march - but then fell in battle that afternoon.

His comrades memorialized him in poems, post-war remembrances and the regimental monument at Gettysburg, which was done in Morris' likeness. Roland was extremely popular, a good-natured fellow fondly remembered. I found two or three mentions of him in the letters of Albert Liscom,* his company C comrade, during the early months of service when the regiment was camped at Darnestown and later Williamsport, Maryland.

Sept 5, 1861

"I have changed my mess and am now in

mess

two where I shall stay. I like it better – as there are many

more

of the old happy family here – there are Bosworth, Goldsmith,

Dickinson, Seabury, D. Walker, A. Johnson, Collis, Morris, G. Ross and

myself – we are all well and happy as ever. Rowland &

Charly

wish to be remembered. Rowland says tell his folks he

received

the box which they sent to him but no letter and has received none

since – he says he shall not write until he receives one from them

because he says he is mad – if you could see him you would not think so

– he is a jolly boy – remember me to his folks – we heard that Bill

[Morris] had

been appointed Lieutenant in Wardwell’s [?] regiment, we want to know

if he is coming out here – we advise him to stay at

home.

The boys are all well and in good spirits."

Feb 16, 1862,

"Mr Morris was

here

last Wednesday Eve.

he came to

see Roland and visit our camp. I

assure you we were glad to see him.

he left here Thursday Eve for Washington to

visit

Bill. Roland got a

furlough for five

days and went with him.

(Roland's brother Bill Morris was in the 22nd Mass. Infantry.)

Comrade Clarence H. Bell remembered Morris in an article titled "Frills," published in Bivouac Magazine, August 1884. Here is the excerpt about Morris.