A Hard March North

June 12th - June 30th 1863

- Introduction

- "Bad Water & Obstructed Roads"

- The Guerilla Mosby

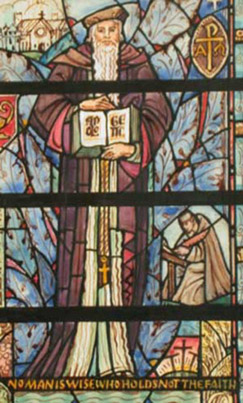

- Brigadier-General Gabriel Rene Paul; 'The Apostle'

- Waiting for Something to Turn Up

Introduction

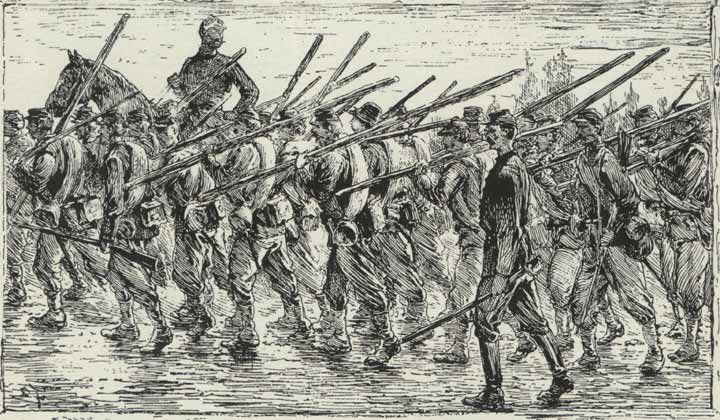

With several quick, long, hot and dusty marches General Joseph Hooker skillfully re-aligned the Army of the Potomac in front of Washington, to counter Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s move north through the Shenandoah Valley from the line of the Rappahannock River. But what General Hooker lacked, was a plan of action. It was largely believed that the Confederate Army out-numbered the Yankees at this time. General Hooker went on defense as he tried to learn Lee’s intentions.

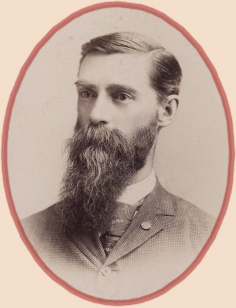

Regimental historian

Charles E. Davis,

Jr. uses cleaned up versions of Sam Webster's diary entries

and

expounds upon them in detail for the narrative of the march north.

Webster's comments are

shorter, and more colorful, describing one watering spot as a

"dirty little stream not fit for a dog." [Postwar portrait of Sam

Webster, right.] Sergeant

John Boudwin of Company A, provides additional details about the march

from his diary.

These are interspersed throughout this section

as seems

fitting. The army was marching through bushwhacker

territory

and Sam Webster, worried for a few days about his

missing younger brother Ike, thinking he was ambushed by Partisan

Ranger John S. Mosby and his men. Captain Charles F. Morse,

Commissary Officer of the '13th Mass,' roundly condemns Mosby's actions

during the war in his 1905 article "Why We Wouldn't Meet

Mosby."

Regimental historian

Charles E. Davis,

Jr. uses cleaned up versions of Sam Webster's diary entries

and

expounds upon them in detail for the narrative of the march north.

Webster's comments are

shorter, and more colorful, describing one watering spot as a

"dirty little stream not fit for a dog." [Postwar portrait of Sam

Webster, right.] Sergeant

John Boudwin of Company A, provides additional details about the march

from his diary.

These are interspersed throughout this section

as seems

fitting. The army was marching through bushwhacker

territory

and Sam Webster, worried for a few days about his

missing younger brother Ike, thinking he was ambushed by Partisan

Ranger John S. Mosby and his men. Captain Charles F. Morse,

Commissary Officer of the '13th Mass,' roundly condemns Mosby's actions

during the war in his 1905 article "Why We Wouldn't Meet

Mosby."

Pages Two and Three of this Section

Page two of this section describes in some detail the week long cavalry battles in the Loudoun Valley, June 17th - June 21st. This is a personal deviation from the history of the '13th Mass,' because my own Great-Great Grandfather, Private William Henry Forbush, formerly of Company K, was present at these battles with the 3rd U.S. Artillery, Battery C. Excerpts from his diary are included in the analysis.

Page three picks up the narrative of the regiment with the 2nd phase of General Hooker's forced marches into Maryland. It was during this time General Hooker resigned from command of the Army of the Potomac, replaced by Major-General George Gordon Meade. Included on page 3 is the last letter home of Private Charles E. Leland, Company B, and a portrait of Color Sergeant Roland B. Morris, both of whom were killed July 1st at Gettysburg.

Sprinkled throughout are some entertaining stand alone articles including memoirs of prussion General, Heros Von Borcke, who was on Confederate General, J.E.B. Stuart's staff, and a short biography of daring, artist-correspondent Alfred R. Waud, both on page 2. Page three has an excellent article by contemporary historian John A. Miller, about the city of Emmitsburg, Md. just before the Battle of Gettysburg. The article has many soldier quotes.

This section ends June 30th

1863, on

the

eve of the Battle of Gettysburg.

PICTURE CREDITS: All images & Maps are from the Library of Congress digital images collection, with the following exceptions: Frank Beard's illustration of soldiers marching is from 'Boys of '61" by Charles Carleton Coffin, accessed via googlebooks; Postwar Portrait of Sam Webster is from the Missouri Historical Society; 'Execution of a Deserter,' & 'Wayside Spring' were heavily altered in photoshop from artist Edwin Forbes book, "Thirty Years After" LSU Press, Reprint, 1993; 'Attacked by Bushwhackers" is from the same book; 'Confederates on the March to Gettysburg' by Alan C. Redwood is from American Heritage "Century Collection of Civil War Art," New York, 1974; The Boston Brass Band circa 1851 is from the website ibew.org.uk; The Bass Drum photo was downloaded from www.fielddrums.com - a civil war blog. ALL IMAGES have been edited in photoshop.

"Bad Water & Obstructed Roads"

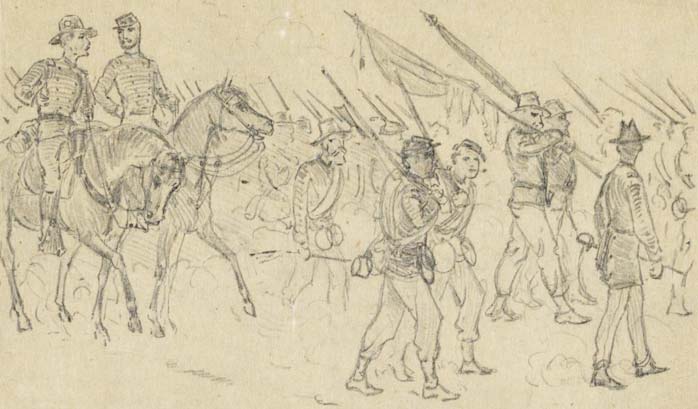

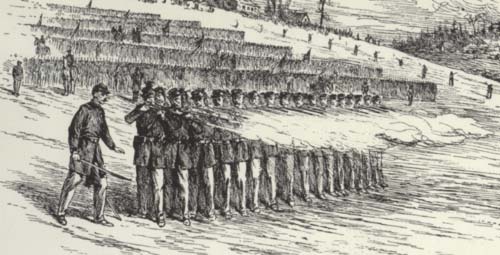

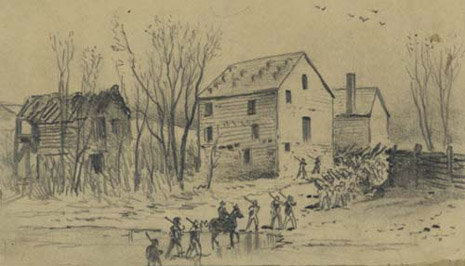

Artist soldier, Charles W. Reed, a buglar with the 9th Mass. Battery, sketched several scenes from army life, including this one of soldiers on the march. His letters home were profusely illustrated.

Excerpts of Sam Webster's diary (HM 48531) are used with permission from The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA. Sam Webster recorded the following:

Friday, June 12th, 1863

March at 5 a.m. by way of White

Oak

Church, Hooker’s

Headquarters, Stoneman’s Switch, Brier and Hartwood Churches, to old

mill on road to Bealton. Took the wrong road once,

and had, altogether, a good long march. I got in

late. We lay for night in an orchard on the grass.

An extra mile or

two...

An extra mile or

two...

From the regimental history, "Three Years in the Army," by Charles E. Davis, Jr., Boston, Estes & Lauriat, 1894.

Friday, June 12.

At 4 A.M. we broke camp and

marched

in a westerly direction via Stoneman’s Switch on the road toward

Bealton Station, following the Rappahannock River, and bivouacking at

Deep Run, a distance of twenty-five miles. It was a scorching

hot day, and the road was very dusty. It occasionally

happened, through somebody’s stupidity, that troops, by taking the

wrong road, had their march considerably lengthened. This was

one of those occasions; several miles of hard work were squandered in

consequence of being misdirected. This kind of

foolishness

does not sweeten the temper of a man who is working for $13 per month.

"Let not the sun go down on your wrath," said Paul

the

Apostle. As the sun was already down when our wrath was

excited, we had nearly twenty-four hours to spare before obeying this

command.

A learned writer on the Holy Scripture says,

“It is acknowledged that neither the Apostles nor Fathers have absolutely condemned swearing, or the use of oaths, upon every occasion, and upon all subjects. There are circumstances wherein we cannot morally be excused from it ; but we never ought to swear but upon urgent necessity, and to do some considerably good by it.”

According to our ideas, instances like the one just described justified a liberal use of “Cuss words.”

The Execution of a Deserter

While we halted at noon to-day an ambulance was driven by us containing a man who was to be shot for desertion. The man belonged to one of the Union regiments, and during the winter deserted to the enemy.

It appears that a detachment of Union troops while on picket saw a soldier in Union uniform acting rather suspiciously, as if he wished to get away unnoticed; where upon he was headed off and captured by men of his own regiment, the Nineteenth Indiana. Under his blue uniform he was found to have a Confederate suit of gray. About him were found papers containing the numbers and locations of Union troops. He was tried by court-martial and sentenced to be shot, and was now on his way to take part in that rather unpleasant ceremony.

His corps was halted for an hour at Hartwood Church, where he was taken into a field, blindfolded and tied, seated on a box that was to be his coffin, and shot by a detail of twelve men.

A

certain number of the guns were loaded without ball in order to deceive

the men into thinking that some other fellow’s gun did the

work. It is an unpleasant duty at best, but the

circumstances, in this case, were particularly aggravating.

When the unfortunate victim was launched into eternity, as

the

newspapers say, the drums were sounded and the bands struck up the

liveliest airs; and while his soul went marching on, we marched on

until we halted for the night, bivouacking in the same field where we

stopped last November on our way from Rappahannock Station.

A

certain number of the guns were loaded without ball in order to deceive

the men into thinking that some other fellow’s gun did the

work. It is an unpleasant duty at best, but the

circumstances, in this case, were particularly aggravating.

When the unfortunate victim was launched into eternity, as

the

newspapers say, the drums were sounded and the bands struck up the

liveliest airs; and while his soul went marching on, we marched on

until we halted for the night, bivouacking in the same field where we

stopped last November on our way from Rappahannock Station.  Some

of the boys expressed a curiosity to know if it was as hot where

the deserter had gone as it was here, where we were marching.

Some

of the boys expressed a curiosity to know if it was as hot where

the deserter had gone as it was here, where we were marching.

Sergeant John Boudwin, Company A, recorded the following in his diary about this execution:

June,

Friday, 12.

Arrived in camp from picket line at

2 AM and laid

down for a nap. at

3 AM revillie

packed up and formed line and at 4 marched towards Falmouth

continued marching all the forenoon with but little rest.

at 1 l/2 p.m. a

deserter executed of the

l9th Indiana he

deserted from his regt - over to the

rebels and was taken prisoner by our forces at Chancellorsville

he was fired on twice

before he was

killed. at

2 PM

continued on march and it was a hard one

untill we arrived at Deep Run. at

6

Oclock having marched 20 miles just very sore and

pretty well used up.

From the regimental history, "Three Years in the Army," by Charles E. Davis, Jr., Boston, Estes & Lauriat, 1894.

Saturday June 13,

In a cloud of dust we marched

ten

miles to Bealton Station, on the Orange & Alexandria Railroad.

The water was about as scarce as whiskey, and so bad that something

ought to have been provided to kill the animalcula it contained.

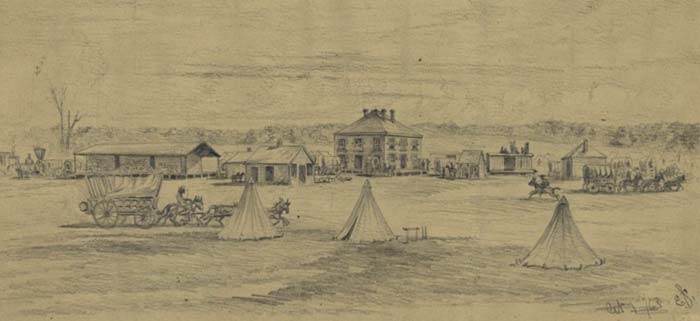

Edwin Forbes sketched Bealeton Station in October, 1863

Austin Stearns'

Memoirs, From "Three

Years With Company K," Edited by Arthur Kent,

Fairleigh

Dickenson Press; 1976. Used

with Permission.

About the middle of June orders were received to march immediately. We obeyed, and marching up to the vicinity of the last winters camps, we halted for several days.

The whole army was in motion, but where we were going or where the enemy were we could not tell. At length we started and moved up the river, bivouacked at night near Bealton Station and resuming the march at day-light, this time going down the railroad towards Manassas. The weather was excessively hot, sweat poured off of us like rain, and the dust covered everything; water was scarce, good water could not be found, the creeks were low, and near all the fording places were filled with dead horses or mules. I remember of coming to a creek and, being very thirsty, thought to fill my canteen before leaving, so I started up creek to find clear water. After going quite a distance I looked and thought I was above all impurities, for I could see none above, and took a long draught and was filling my canteen when a comrade asked me “how I liked the water.”

“Firstrate” I replied.

“I thought so,” he said, “when I saw that dead mule there,” pointing at the same time to a bunch of bushes just above me in which lay the swollen carcass. The water being down and canteen filled, I thought it as good as any I could find so, saying nothing more, I went on my way.

It was not the first, and neither was it

the last, that we boys were

obliged to drink during our three years, but then we liked to laugh at

one another when we had the laugh on our side, and many were the jokes

and hearty laughs we had around the camp fire in recalling just such

things as this. The stories never lost anything in the

telling.

It was not the first, and neither was it

the last, that we boys were

obliged to drink during our three years, but then we liked to laugh at

one another when we had the laugh on our side, and many were the jokes

and hearty laughs we had around the camp fire in recalling just such

things as this. The stories never lost anything in the

telling.

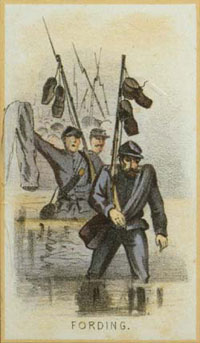

Obstructed Roads

Sergeant John Boudwin recorded the two day march on the 14th and 15th in his diary.

June, Sunday, 14. 1863

Left Bealton Station at 8 A.M. and marched towards

Mannassas the roads now verry dusty and the sun verry

hot Marched till 9 PM and halted till we

arrived at Kettle Run halted for one hour and made

some coffee. at 10 l/2 p.m. took up our line of march again

and crossed a large Brook which it took some time to do so.

and feeling verry tired (the whole of us) their was not much

head way made. at 12 midnight halted for ½ hour and started

again.

over...

June, Monday, 15. 1863

...and arrived at Mannassas at 3 l /2

Monday

Morning. laid down to sleep and and slept till 8 A.M. and

cooked some coffee. took up our line of

March again at 9. toward Centerville halted on our way at

Bull Run and have a bath feel much better for it- arrived at

Centerville at 2 P.M. and laid the rest of the day in expectations of

marching. receive rations of coffee & hard

bread. camped for the night

here feel used up.

From "Three Years in the Army," by Charles E. Davis, Jr.

Sunday, June 14,

It was evident that an army must not be

hampered by religious principles. We wondered if Miles Standish ever

marched his army on Sundays. “In war there are no Sundays,”

as Daniel

Webster once remarked.

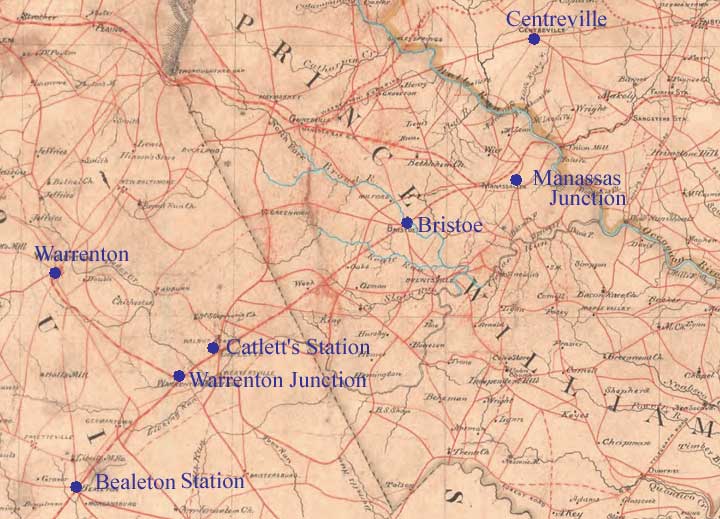

We started promptly at 8 A.M., marching through [Warrenton]* Junction and Catlett’s Station, near where we were stationed a year ago, and thence to Kettle Run, which place we reached at sunset and where we halted for an hour to cook coffee, then resumed our march, crossing Broad Run near Bristow Station, at the old mill, arriving at Manassas Junction at 3.30 A.M., a distance of twenty-three miles. All day long we were subjected to wearisome delays caused by obstruction in the road by wagons and artillery, fording brooks or crossing streams imperfectly bridged, until our patience was well-nigh exhausted. When the order was given to halt, the men dumped themselves on the damp grass, and went to sleep.

Artist Correspondent, Edwin Forbes sketched the old mill at Broad Run in October, 1863.

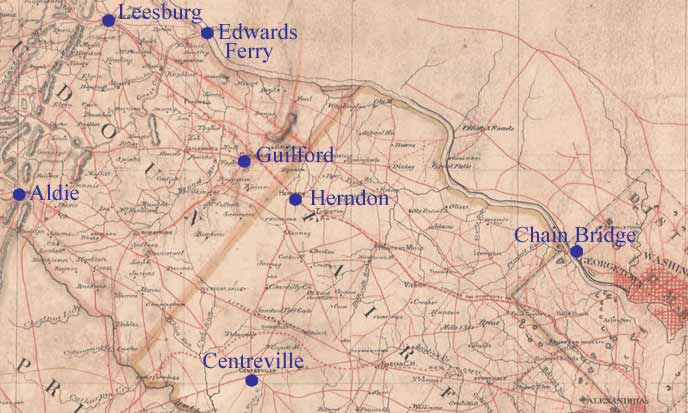

The map shows the distances marched and the route taken. Broad Run is outlined in light blue color, running through Bristoe Station.

Monday, June 15.

After five hours’ rest we

started

again, marching eight miles to Centreville, which point we reached

about noon, and where we remained until the 17th. The

continued northerly direction we were pursuing began to excite the

curiosity of the boys as to what was going on. As we were not

in receipt of papers nor in the confidence of General Hooker, we could

only make guesses. In the meantime we kept pegging on toward

Boston, Mass., pumping all the people collected on the road-side as to

the whereabouts of General Lee, or whether they had heard the war was

over, or that General Washington was dead. “No, massa; don’t

know nuffin at all.”

“You tell General Lee we’ll be back in the fall, but just now we’re going to Saratoga, where it’s cooler.”

“Yes, massa.”

The thirst for information was so great about this time that the “campaign gossips” put in a good lot of work, resulting in some of the most ridiculous yarns ever heard in the army.

We did have ocular proof to-day that Lee’s army was marching north. When you see geese flying north, look out for warm weather; when you see rebels marching north, look out for warm fighting. The country was full of guerillas, and that enterprising cutthroat, Mosby, did a thriving business in capturing and mutilating the bodies of Union soldiers.

*Davis wrote 'Manassas' Junction instead of Warrrenton Junction, which is correct.

The Guerilla Mosby

Confederate Partisan Ranger John Singleton Mosby was a controversial figure during and after his time. He constantly claimed his command was an independent arm of the Confederate army. His domain was the Luray Valley in Northern Virginia. His adversaries claimed he and his men were bush-whackers, thieves and murderers. The following two articles leave no doubt as to the opinions of the writers. The first, By Captain Charles F. Morse of the 13th, is from 13th Regiment Association Circular #18, December, 1905. Secretary Charles E. Davis, Jr. introduced the article this way:

"Captain Charles F. Morse, who has consented to the republication of his reasons for not meeting Mosby, was a commissary of subsistence and a graduate from the Thirteenth. At one time he was commissary of all the armies operating under Grant. He had exceptional opportunities for knowing the doings of Mosby's men, and Charley Morse never made a statement that was not true. In this instance he has been obliged to refrain from relating all he knew about Mosby's guerillas, because a consideration for the decencies of our language will not permit the publication."

WHY WE WOULDN'T MEET MOSBY.

BY CHARLES F. MORSE.

Some years ago we received an invitation to meet Col. John S. Mosby, at Young's Hotel, Boston, where some misguided but well-intentioned men, having little acquaintance with his career, sought to show him attentions which, in our opinion, were unmerited.

We didn't accept it. We didn't want to see him then, and we never wanted to when he was a bushwhacking guerilla down in Virginia, and was murdering Union soldiers. The war is over, and all its strifes, animosities, bitternesses and hates ought to be laid forever at rest. We have met a large number of men, both officers and privates, who were engaged in the war on the wrong side, and have been only too glad to fraternize with them, and talk about the old unpleasantness, but they were soldiers, who bravely fought and nobly suffered in a wrong cause, which now they see was wrong. They were brave soldiers and honorable enemies. Col. John S. Mosby was neither a brave soldier nor an honorable enemy. All through the war he led a gang of bushwhacking outlaws, who, though preying only on the Union army and its supplies, were none the less a gang of execrable thieves, robbers and murderers, and John S. Mosby was as villainous a scamp as any of the detestable gang with which he was connected.

It is all very well for him to glibly talk about what he and General Stuart did in the way of raids on our supplies, but we have faith enough in J. E. B. Stuart's manliness and soldierly qualities to believe that if he were where he could hear this blustering braggart boast of his achievements, he would promptly disown him, and deny that he ever availed himself of the dastardly cut-throat's help. Stuart was a fighter as well as a raider. Mosby was an assassin as well as a thief. All through the war he hung on the rear of the army, seeking chances to pillage and murder, and many a noble officer and soldier has been murdered and robbed by him and his outlaw gang.

In the fall of 1863, while the army under General Meade was advancing toward the Rapidan, after falling back to Manassas Junction, when Lee's feint on Washington made that move prudent, a staff officer of our army had occasion to go from the vicinity of Warrenton to Bealton Station. His business was urgent, and it not being convenient to take an orderly along with him, he rode alone. When near Fayetteville he was joined by another person wearing a staff officer's uniform, but without anything to indicate the corps he belonged to. Thinking, of course, that it was one of our own officers he rode along unsuspectingly, until a piece of woods was reached, when the stranger suddenly drew a revolver and shot the officer, and, leaving him lying on the ground, apparently dead, hastily rode away with his horse and equipments, probably not daring to stop long enough to strip him of his uniform.

That stranger was one of Mosby's men, if not Mosby himself.

On the occasion of that falling back of Meade's, one of the guards of the Third Corps supply train, a young man from Malone, N.Y., belonging to the One Hundred and Sixth N.Y. Volunteers, was shot down in the road, near Wolf Run Shoals, by a bushwhacker concealed in the bushes by the side of the road.

That is the kind of work Mosby's men were continually doing, and of which Mosby boastingly claimed the credit.

After the Sixth Corps had repulsed the attack on Washington, in 1864, it moved up the Potomac to Harper's Ferry, where it crossed into the Shenandoah Valley. As the corps pushed on up the valley, the supply train followed, taking the route via Charlestown, where John Brown was hung five years before. Capt. Evan M. Buchanan, of Lochiel, Penn., a relative of the Camerons,* was commissary of subsistence of the third division. When near Charlestown some of the officers with the train rode a little distance away from the road, to visit a substantial looking residence - a not unfrequent custom, - and stayed chatting with the ladies of the household until the rear of the train had passed, when they started to catch up with it. Captain Buchanan, always rather moderate in his movements, was lingering behind, when one of the party advised him to hurry up or he would be gobbled by Mosby's men. But he didn't hurry, and the rest of the party started off, leaving him behind with his orderly. Scarcely was the party out of sight when a squad of Mosby's men swooped down on the house. The orderly escaped, but Captain Buchanan was captured, and was never seen alive again.

James Harris, Captain Buchanan's clerk, was a cousin of Don Cameron's also and, with the Cameronian influence at Washington, was able to make diligent search for his chief. It was found that he had been taken to the vicinity of White Plains, on the other side of the mountains, and there killed and buried. After long search the place of his burial was found, and the body exhumed, when it was discovered that his body had been shockingly mutilated, and that in all probability the mutilation had been done before the death of the victim of the diabolic cruelty !

This was the work of Col. John S. Mosby and his gang.

*One of the prominent members of the Cameron family during the war was Simon Cameron, a senator from Pennsylvania and President Lincoln's first Secretary of War.

The following anecdote, which holds a more neutral point of view of Mosby, comes from the Military Magazine Bivouac, January, 1885. It relates more directly to the Army of the Potomac's march north to Gettysburg.

The 11th Pennsylvania Volunteers were in the First Brigade of General Robinson's Division, the '13th Mass.' were in the Second Brigade of the same division.

From Bivouac, An Independent Military Monthly, Volume III, 1885; Edward F. Rollins, George W. Powers, & George Kimball, Editors. [January, 1885, p. 23.]

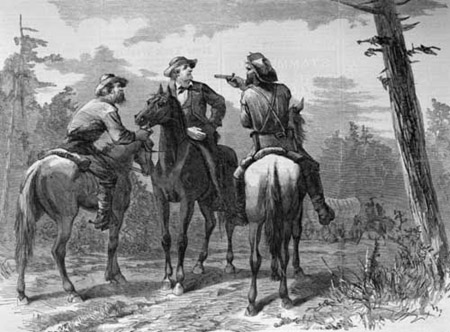

The following, from “The Story of the Regiment,” (history of the Eleventh Pennsylvania) illustrates the means taken by Lee to ascertain Hooker’s movements during the march to Gettysburg and presents the famous guerrilla chief in a more favorable light than many have been wont to regard him.

“On the march from Centreville to Guilford Station we had an instance of the daring exploits of the guerrilla Mosby, within whose domains we then found ourselves. Two clerks, belonging to the brigade commissary, rode off some distance from the troops to procure a supply of forage for the horses. Scarcely had they left the road over which our wagon-train was passing, on their way to a farm-house across the fields, when, in going through a narrow strip of woods, they fell into the hands of Mosby. The party, consisting of the guerrilla chief and a dozen men, dressed in Federal uniform, were mistaken for a squad of our own cavalry. Relieving the clerks of the pistols they always carried in their belts but never used, the prisoners were ordered to remain seated on their horses, and observe perfect quiet. In a little while, placing our ‘boys’ in the centre of the squad, and intimating what would be the result in case of the slightest alarm, the guerrillas boldly galloped out into the road, riding some distance along with the train, and again taking to the woods on the opposite flank. Except to disarm them, not the slightest indignities had thus far been offered, and Mosby seemed determined to convince his captives, not only by words, but by actions, that he was not the style of person the Yankees represented him. Said he:

‘Your papers speak of us as guerrillas, and every murder committed between the Potomac and the Blue Ridge is blamed on me or some of my men. These charges are all false. We are an independent command, to be sure, but a part of the Confederate cavalry, and only kill when we cannot capture, just as your men do. It is my business now to get all the information I can of your movements, and that is what I have been doing to-day. We have gone all along your trains, and from the marks on the wagons, and conversation with the drivers, I know how many corps are moving in this direction, and where you will probably bivouac to-night. If any horses should stray away from camp or men either, for that matter, they may be among the missing in the morning.’

Riding up to a house, partly hid in an apple-orchard, another source from which Mosby derived his information was discovered. The farmer met him at the gate with every expression of hearty welcome. Two Yankee soldiers had been there an hour before, to whom he had given dinner in the hope of getting some news out of them. ‘But they were a stupid pair,’ said the farmer, ‘and only knew that they belonged to the Eleventh corps.’

Mosby retained his prisoners until next morning, and then released them on parole. If he had not kept their horses, thus compelling the clerks to walk ten or twelve miles to overtake the brigade, so far as their experience went, the partisan chief might have received more credit for cleverness than he deserved.”

Brigadier-General Gabriel Rene Paul; 'The Apostle'

From Three Years in the Army, by Charles E. Davis, Jr.

The First Corps had been acting thus far on our journey as rear guard to the army.

Tuesday, June 16.

We remained quietly resting.

The

regimental sutler arrived in camp, and those of us who had money or

credit proceeded at once to fill the aching void caused by short

rations and hard work. We were serenaded by the band of the

Thirty-third Massachusetts, a bit of politeness and consideration that

we highly appreciated. It had a good effect on the boys, as

good music

always does. We would have liked mighty well to have asked

the

boys to “licker,” but there was “no balm in

Gilead.”

During the day we received the rather startling intelligence that the Confederate army was in Maryland and prancing along toward a cooler climate, as though they liked it.

Hooker informed us that “the enemy must leave his intrenchments and fight or ingloriously retreat,” etc., and now he was ‘way north of us.' If Lee had lost his way, there was nothing for us to do but hunt him up and put him on the right track.

From the Diary of Sam Webster (HM 48531) Huntington Library, San Marino, CA; used with permission.Wednesday, June 17th,

March at sunrise, but turn off

toward

“Chain bridge” and camp

near Herndon Station. Brigade under command of Gen. Paul,

late of the New Jersey, 9 month, Brigade, of the 1st

Division. He was familiarly greeted as the “apostle” very

soon after he was known to the men. The day was extremely

hot, and I got so near “played” as to heave my overcoat, which I had

stuck to so far. Lay just across the R.R.

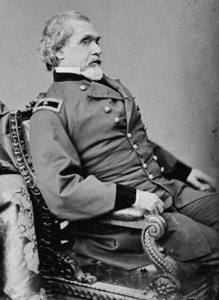

General Gabriel Rene Paul, pictured, right, was wounded in both eyes at the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1st, 1863. The only other likeness I have found of him dates to 1846, during the War with Mexico.

The regiment marched with its division from Centreville towards the Chain Bridge on the Potomac River outside Washington, D. C., before turning to march to Herndon on June 17th. Meanwhile the Cavalry was sent out on a reconnaissance, this day to the mountain pass at Aldie. -See page two of this section.

Charles Davis, jr.,

resumes:

Wednesday, June 17.

We celebrated the battle of

Bunker Hill by turning out at 2 o’clock in the morning to prepare for

marching. We got away by 3 and marched toward Chain Bridge,

changing our direction before arrival at that point, and continued on

to Herndon, a distance of sixteen miles. Our new brigadier-general was

Gabriel R. Paul, whom the boys dubbed the

“apostle.” He was a brave and excellent

officer.

This was so hot a day that sixty men in the corps were sunstruck. The thermometer registered 100˚.

Sergeant John Boudwin of Company A, recorded the difficulty of this long march:

June, Wednesday,

17. l863.

Came in pleasant. at 2 A..M.

Revillie got some breakfast and at 3 formed line

and at 4 started on the road and marched through Centreville.

the sun poured down on us with but little mercy the

roads verry dusty and it made very dissagreeable marching. 4

men died on the march from fatigue several wer sun

stroke. arrived at Guilford St. at 3 P.M. and

Bivouacked for the night. it was as hard a march as we have

had and the men did straggle. have a good Bath in the Brook

and feel much better. the Rail Road here is all torn up - one

year ago to day we wer on our March from Front Royal for Mannassas.

Charles Reed sketched his unit marching through Centreville, 3 days later on June 20, 1863.

Charles Davis, jr.

continues:

Thursday, June 18.

We struck tents in the

morning,

expecting orders to march ; but no orders came, and so we

laid quiet,

putting in all the sleep we could, which was considerable, in spite of

the burning heat of the sun, while General Lee was amusing himself in

“Maryland, my Maryland.” *

*General Robert Emmett Rodes Division of Richard Ewell's Corps crossed the Potomac River into Maryland at Williamsport on June 15. General A. G. Jenkins Cavalry pressed forward to Chambersburg, PA. A second Confederate division crossed the next day.

Friday, June 19.

Marched three miles to Guilford

Station, on the Leesburg Railroad. Everything we could

dispense with was now thrown away, even at the risk of getting in the

same condition in which St. Thomas a Becket was found when he died, -

lousy.

Guards were put on the fences to prevent our taking rails. About half the regiment was put on picket, and were called in during the night, returning in a violent storm. Orders were countermanded, and back on picket went we. Noticing the guard had been taken off the fences, we “hooked” a lot of rails, which we carried along with us. “It is a sin to steal a pin, much more to steal a bigger thing.” These rails were useful, as the streams were very much swollen by the rain, whereupon the rails were fastened together, and used as bridges. [Note: John Boudwin and Sam Webster both write the Rails are used to lie upon - as a barrier against the wet ground.]

"Getting Ready For Supper" by Edwin Forbes, from his memoir, "Thirty Years After."

General Orders,

No. 41.

Headquarters

First Brigade,

Second Division, First A.

C.

June 22, 1863.

I. In order to ensure uniformity, no words of command or forms of parade, "not prescribed in the General Regulations or in Casey's tactics," will be allowed in the regiments of this brigade.

II. It is expected at guard mounting and on parade and reviews the officers and enlisted men will be neatly dressed, and their accoutrements put on in a soldier-like manner. On parades pioneers will be in the ranks with their respective companies.

The color guard will consist of one sergeant and five corporals, who will be selected for accuracy in marching and soldier-like deportment. The companies being numbered from right to left, the first sergeants, when they report the results of the roll-call, will say in a quick, firm tone, "First company all present," or "Second company three absent," and so on as the case may be.

III Sentinels will not be permitted to sit, read, or talk on post, or to bring their pieces to the order. They will habitually walk their post, watching vigilantly and allowing no infractions of orders.

By command of

G.R. Paul,

Brigadier-General

Commanding.

“And God wrought special miracles by the hand of Paul.”

We remained at Guilford Station until June 25, engaged in such light amusements as dress parades and brigade drills, sandwiched with a liberal allowance of guard duty.

Waiting for Something to Turn Up

Letter of Warren Freeman, Company A

Near Broad Run, At Guilford Station, Va., June 20.

I have received no letter from home since the one dated June 7th, we have had no mail lately, but have had some severe marches.

On Thursday night, June 11th, we were out on picket, when the order came to march; we got into camp at one o’clock, and at six in the morning we were all ready to move. We marched twenty-two miles this day; it was terrible hot and dusty, and during one of the halts we shot a man for desertion. He belonged in the First Division; he was taken prisoner from the rebels at Chancellorsville. Next day marched thirteen miles, to near Rappahannock Station. On the next day, Sunday, the 14th, we marched through Catlett’s Station to Manassas Junction, arriving at about three o’clock Monday morning; distance twenty-one miles, weather still very hot. Monday marched to Centreville, distance seven miles. Lay there the remainder of the day, and also the following day. On Wednesday we marched to within three miles of this place; the distance was about fourteen miles. Quite a number of our poor fellows, while on the march, fell dead in the road, being overcome from the excessive heat and dust.

When on the march I had the pleasure of meeting with two West Cambridge boys, George H. Cutter and Joseph P. Burrage. George is in the Third Wisconsin. Joseph is in the Eleventh Corps. He did not seem at all natural, and was not inclined to say much. Yesterday we came to this place. Saturday night we had a severe rain-storm, and in the midst of it we had orders to pack up and be ready for a march. Our pickets were drawn in, but we did not move; still we are expecting to leave every moment. I do not know what we are going to do, neither do I know what the rebels are about, not having seen a paper lately. I think the rebel army is not far off; I hear cannonading frequently. I presume we must have a brush with them soon, but we will hope for the best. You had better not send me another box at present.

Colonel Leonard is in command of the regiment now, and General Paul commands the brigade. I have seized a few moments to write these lines, not knowing when there will be a chance to send them off.

I bid you all farewell.

Warren.

Diary of Sergeant John Boudwin, Company A:

June, Friday, 19. l863

Came in pleasant. at l0 l/2

left camp and marched 4 miles towards Leesburg and camped

near Goose Creek. at 7 P.M. orders to send out

picket and at 9 - picket called in orders to

march struck tents

- and it commenced to rain heavily got wet through. picket

sent out again and ordered to pitch tents-rained all night quite hard

slept on some rails - had a dress parade at sun set.

June, Saturday, 20. 1863

Came in Cloudy. cleaned up Rifle and

Equipments. Nothing occurred during the day- firing in the

vicinity of Leesburg - had orders to march in the eve but did not go -

heavy shower. wrote a letter to sisters M.J. & J.

June, Sunday, 21. 1863

Came in pleasant. at

sunrise..heavy firing at Leesburg by Battle going

on. ordered to pack up and be ready to

march - packed up and laid waiting orders all day.

at 5 PM ordered on picket. Left camp at 6 and

marched 2 miles found no picket line - sent back to camp and could not

find any thing about it- Col Tilden of 16th Maine went in

search and at last found the line. While awaiting the girls

in a house close by sang several seccess-songs such as My Bonnie Blue

Flag and Gallant South Carolina. at last our Boys sang the

Star

Spangled Banner and several others. they called us Lincoln's

hod carrier. - Took no notice of them - laid down

and had a little sleep.

June, Monday, 22. l863

At 1 A.M. was aroused and marched to the picket

line and after traveling several miles arrived their at 4

o’clock I was in charge of station No. 2 near the

town of Franklin and at the house of John Solomon - wrote part of a

letter to sister in the House. at 1 P.M. the picket came from

camp to relieve us and we marched back to camp and arrived

their at 11 o’clock. the Regiment had a Battalion

drill while we were on picket. Nothing new

occurred. one of the men of the 91st Pa was shot dead while

up in a cherry tree by a gurilla. he was buried near

the

camp. One of our Forager Martins

and Genl Reynolds

guide was taken prisoners while out a short distance from camp and

paroled. this part of the country is where the Mosby cavalry

was raised.

June, Tuesday, 23. l863

Came in pleasant. had

Regimental Inspection by Capt. Livermore - afternoon Battallion drill

in the afternoon by Col Leonard. Nothing new during the day -

mail came and received paper. While some of the Division

Teamsters were out in the woods playing cards they were fired on by

some

Rebel Cavalry. they made for camp in a hurry - eve dress

parade.

From The Diary of Sam Webster, (HM 48531) Huntington Library, San Marino, CA, used with permission.

Wednesday, June 24th,

Brother Ike arrived this

morning. Was picked up by

the Provost, and has been sick. Strict orders against going

in or out of camp. Can’t even go out for water, and have to drink the

dirty water of Broad Run, after a division above us has washed in

it. We filter it through the sand. Get in and out

of camp by going along the line pretending to want in, if want out, or

vice versa. Of course on denial of our request by the guard

we place ourselves on the right side of the line, - but it don’t do to

get caught out.

General order read night before last relating to Pleasonton driving the rebel cavalry to Ashby’s Gap. The 11th Corps lie in Leesburg, and all the army between there and Fairfax Court House. General Paul seems to think us all Jerseymen and recruits, if we may judge from the various orders and direction he gives at Brigade Guardmounting. – The greatest trouble is that he never does it twice alike.

Six young damsels at one house near the piquet, - one of whom sings the "Bonnie Blue Flag." One of the fellows says he could “get a double barreled drum into her mouth, if it was only a little bit larger.” On Saturday morning last the boys found themselves as “reserve” outside of the line of piquets they had established. This was after the order to march was countermanded, and they had to go out in the rain.

Next Page - "Cavalry Fights at Aldie, Middleburg & Upperville"

Return to Top of Page | Continue Reading

© Bradley M. Forbush, September 21, 2014.

Page Updated September 21, 2014.