Back in Camp

May 8th - June 11th, 1863

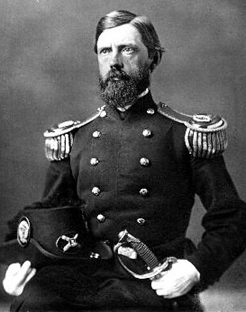

General Joe Hooker and Staff, June, 1863.

[Officers Standing]

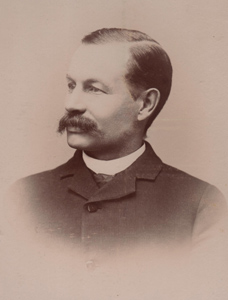

1) Captain C. B.

Comstock; 2) Captain J. B. Howard;

3) Lt.-Col. N.H. Davis; 4) no name

listed; 5) Captain D. W. Flagler; 6) Captain J.R.

Coxe; 7) no name listed; 8)

Major W. H. Lawrence; 9) Lieutenant J. C. Bates;

10) Lieutenant F. Rosencrantz;

11) no name listed; 12) Captain Ulric Dahlgren;

13) Lt.-Col. Joseph Dickinson; 14)

Lieutenant Charles E. Cadwalader.

[Seated]

Colonel H. F. Clark; General

H.J. Hunt; General Rufus Ingalls; General Joseph

Hooker; General Daniel

Butterfield.

A SPECIAL THANK YOU to JEFFREY BRIDGERS at the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS who answered several e-mail inquiries regarding the identities of the men in this photo, and other questions about the civil war sketches of Edwin Forbes, and Alfred R. Waud.

- Introduction - What's on this Page

- Back In Camp May 9 - 17

- Change of Camp; Change of Brigade

- Letters Home; Edwin Field and Charles Adams

- Major Gould's Speech & General Reynold's Review

- JUNE, 1863

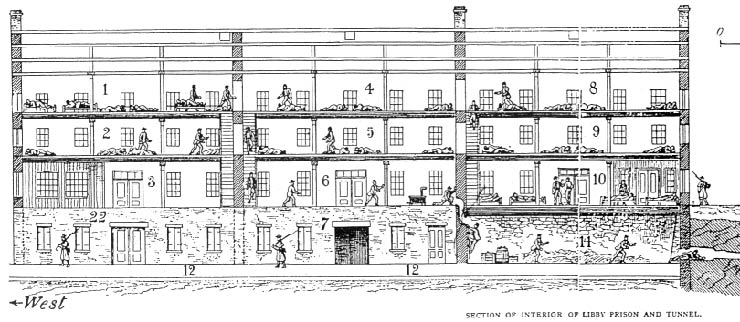

- "Libby Prison" by John S. Fay

Introduction - What's on this Page

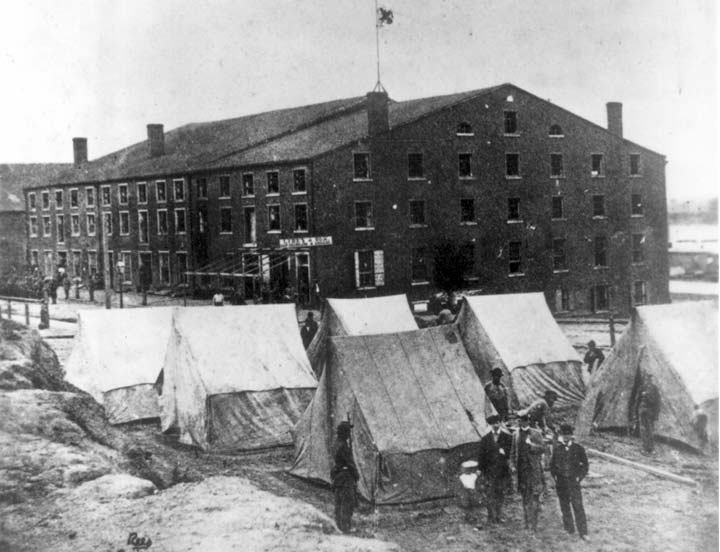

"Union Soldiers entrenched along the west bank of the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg, Virginia." Photographed by Andrew J. Russell, between April 29 and May 2, 1863. Formerly misidentified with the title "Union Soldiers in Trenches before Petersburg, Dec. 1864."

The Most Serious Setback of the War

Chancellorsville was the bloodiest battle of the war to date with 17,000 Union casualties. On May 6 General Hooker telegraphed President Lincoln that he had re-crossed the Rappahannock. That afternoon, Lincoln and General-in-Chief Henry Halleck left Washington to visit Hooker and check on the condition of the Army of the Potomac. Corps commanders were gathered together to discuss the morale of the troops. Reasons for the retreat were excluded from the conversations. “Lincoln told them he feared that the effect of the defeat at home and abroad would be more serious than any other setback of the war.”1 The President returned to Washington the next day but instructed Halleck to stay and learn all he could. On May 7th Lincoln wrote Hooker to ask if another move might be made while the enemy’s communications were still disrupted, (a result of General Stoneman’s Cavalry raid behind Confederate lines). Hooker’s reply suggested he had ideas and was planning, a move "in which the operations of all the corps, unless it will be a part of the cavalry, will be within my personal supervision.”

General Halleck returned to Washington and reported that the corps commanders blamed Hooker and his “inexcusable” actions for the defeat at Chancellorsville. Most of them wanted Hooker replaced. Lincoln decided to be patient in the matter. The President and the General met on May 13th when Hooker announced he was ready to make a new move on the morrow. In preparation for this un-named move, the camps of the First Corps were moved closer to the Rappahannock.

Lincoln discouraged the plan and expressed the opinion that the window of opportunity had passed away; - the enemy had time to restore its communications, “regain his positions and actually receive re-inforcements. It does not now appear probable to me that you can gain any thing by an early renewal of the attempt to cross the Rappahannock.” He also warned Hooker, “some of your corps and division commanders are not giving you their entire confidence.”2 The un-named move did not happen. Another problem with the Army of the Potomac which delayed Hooker’s plans was the loss of 23,000 two years and 9 months men, whose term of enlistment expired between late April and mid June.

To compensate for the loss, divisions and brigades were consolidated. The 3rd Brigade was eliminated and the '13th Mass.' were put into the 1st Brigade of their Division. Union artillery was also reorganized to increase effectiveness. Artillery brigades were detached from infantry divisions and one each assigned to the various corps. Five brigades were grouped into the artillery reserve. Ammunition trains were placed in command of artillery officers rather than infantry quartermasters.3 Efficiency increased. General Lee also re-organized his army.

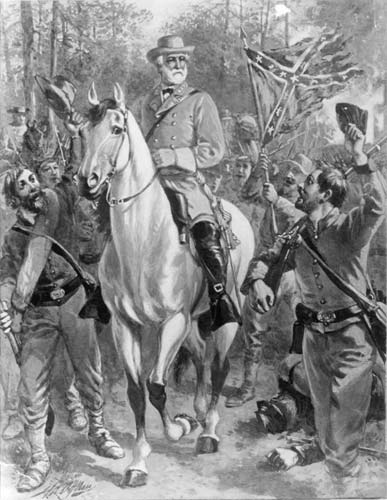

He formed his Confederate troops into 3 corps with 3 divisions each and re-grouped his artillery. With the admirable success at Chancellorsville, Lee's thoughts returned to planning an invasion of the north.

Confederate Concerns Bear a Daring Strategy

General U.S. Grant’s Vicksburg campaign met with great success in May, 1863. Grant cut his army off from a supply base, and moved behind Vicksburg to attack the city fortress from the rear. He captured Raymond, Mississippi May 12, and Jackson, Mississippi May 14. Then he turned his force west. He battled Confederates away from Champion Hill May 16, Big Black River May 17, and pushed on to Vicksburg. Two bloody frontal assaults failed to break through Confederate defenses, May 19 & 22, so Grant settled in for a siege.

Map of Grant's

Vicksburg Campaign, May 15 - 19, 1863

Map of Grant's

Vicksburg Campaign, May 15 - 19, 1863

Jefferson Davis wanted to send troops from Lee’s army to bolster beleaguered Confederates in the west. General Lee convinced Davis he had a better plan. Lee preferred an offensive campaign in the North, to terrorize the northern people, strike the Army of the Potomac along the way, increase anti-war sentiment already on the rise, and force the Lincoln administration to recognize the Confederacy.

Anti-war Sentiment in the North

Successive Union defeats in the East, gave voice to political opponents of the Lincoln Government. Clement L. Vallandigham representative from Ohio, was a leading spokesman for the Peace Democrats, nicknamed Copperheads. In January following the Emancipation Proclamation he spoke in the House of Representatives on “his favorite themes: that the South could never be defeated, and the war had only produced “defeat, debt, taxation, sepulchers…the suspension of habeas corpus, the violation …of freedom of the press and of speech…which have made this country one of the worst despotisms on earth.” 4 He urged, “stop fighting, Make an armistice.” His speech was cheered.

He gave a similar speech in Ohio when home on recess, campaigning for the Democratic Gubanatorial Nomination of that state. General Ambrose Burnside, in command of the Military Department of Ohio, had proclaimed that, "The habit of delaring sympathy for the enemy will not be allowed in this department." Vallandigham was baiting Burnside. Shortly after giving the speech he was promptly arrested for treason and a military trial sentenced him to imprisonment for the remainder of the war. The arrest caused Lincoln considerable problems. Throughout May and June, Democrats protested Vallandigham’s incarceration with petitions and large rallies in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York. Considering the situation, Lincoln decided to exile Vallandigham to the Confederacy, rather than imprison him at Fort Warren in Massachusetts Bay. He was handed over to Confederate authorities in Tennessee on May 25th. Lincoln addressed the matter in a June 12 letter:

“Ours is a case of rebellion in fact, …a clear, flagrant, and gigantic case of rebellion; and the provision of the Constitution that “the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it,” is the provision which specifically applied to our present case.” This provision plainly attests the under standing of those who made the Constitution, that ordinary courts of justice are inadequate to “cases of rebellion.” Mr Vallandigham avows his hostility to the War on the part of the Union; and his arrest was made because he was laboring, with some effect, to prevent the raising of troops; to encourage desertions from the army; and to leave the Rebellion without an adequate military force to suppress it. He was not arrested because he was damaging the political prospects of the Administration, or the personal interests of the Commanding General, but because he was damaging the Army, upon the existence and vigor of which the life of the Nation depends. He was warring upon the military, and this gave the Military constitutional jurisdiction to lay hands on him.” 5

On June 3rd,

Democrats led by New York

Mayor Fernando Wood met at the Cooper Institute and urged peace.

The

same day Lee began his advance.

Once the Confederate authorities approved his invasion, Lee re-enforced his army. He asked to recall the men Jeff Davis had earlier detached for duty further south. After some negotiations, Lee got several of his veterans back, but not all. Some untried troops re-filled his ranks. His army numbered 75,000 men. On June 3rd he sent a division west to Culpeper and kicked off his campaign. He continued funneling troops west each successive day.

Lee wanted to make the first move before Hooker, and he did.

June; Hooker Considers a Thrust SouthIn late May & early June, low water levels in the Rappahannock made it crossable in several places and less of a protective barrier between the two armies. On June 3rd the 5th Corps was directed to re-enforce the guard at Banks Ford. Then, June 4th, when Hooker became aware of Lee’s activity he ordered the 2nd, 11th, and 12th Corps to be ready to move. Cavalry was ordered out toward Culpeper.6

On June 5th, knowing Lee was shifting troops west he established a bridgehead at Franklin’s Crossing to determine Rebel strength on the opposite side. Federal Artillery blasted away at Rebel rifle pits to cover the bridge building and crossing. The bombardment temporarily halted Confederate General Ewell’s march to Culpeper. In the morning Hooker proposed to President Lincoln another plan to cross the river and pitch into the rear of Lee’s departing army. President Lincoln promptly replied:

“I have but one idea which I think worth suggesting to you, and that is in case you find Lee coming to the north of the Rappahannock, I would by no means cross to the South of it. If he should leave a rear force at Fredericksburg, tempting you to fall upon it, it would fight in intrenchments, and have you at disadvantage, and so, man for man, worst you at that point, while his main force would in some way be getting an advantage of you Northward. In one word, I would not take any risk of being entangled upon the river, like an ox jumped half over a fence, and liable to be torn by dogs, front and rear, without a fair chance to gore one way or kick the other.”7

Hooker persisted and for the next 5 days continued exploring the possibilities for an aggressive crossing en masse.

On June 6th

Hooker ordered the 6th

Corps to throw a force, the entire corps if necessary, across the river

at Franklin's Crossing, to test

the enemy’s strength. It didn’t take long

to find the enemy concentrated in front.

“It is not safe to mass troops on this side,” was the report

received

at

headquarters.

On the 7th, thinking Lee was planning a raid around his lines, similar to that of August 1862, Hooker ordered a large cavalry force with infantry supports west, to fall on the Confederate Cavalry near Culpeper, and destroy them.

On the 8th he requested a topographic study of Rebel defenses along the river at some of the nearby river crossings. Meanwhile, - his cavalry & infantry expedition surprised Confederate Cavalry at Brandy Station, and a sanguinary fight ensued. For the first time in the war, the Union Cavalry performed on a par with its Confederate counterpart. The fight was inconclusive but the Confederates received a good drubbing.

By June 10, two of Lee’s three corps had shifted to Culpeper with one remaining behind at Fredericksburg. Again, General Hooker wrote to President Lincoln and proposed a major thrust across the Rappahannock to compel the enemy to abandon its present position around Fredericksburg. The Federal force would then rapidly advance to Richmond and give the Rebellion a mortal blow. Lincoln and General in Chief Henry Halleck quickly said no. Lincoln in part replied,

“I think Lee’s Army and not Richmond, is your true objective point. If he comes toward the Upper Potomac, follow on his flank, and on the inside track, shortening your lines, whilst he lengthens his. Fight him when opportunity offers. If he stays where he is, fret him, and fret him.”

With his plans for a move south rejected and with Lee’s infantry moving northwest, Hooker shifted his army to meet potential enemy threats on his flank. On June 11th, dispatches were made accordingly, and the First Corps ordered to march the next day to Berea Church.

FOOTNOTES

1. “Chancellorsville 1863; The

Souls of the Brave” by Ernest B. Furgurson,

Vintage Civil War Library Edition, 1993. p. 331.

2.

“Abraham Lincoln, Speeches and Writings;” Library of America,

1989. p. 447, Lincoln to Hooker, May 14, 1863.

3. “The Gettysburg Campaign, A

Study in Command;” Edwin B.

Coddington, Touchstone Edition, 1997. p. 40 - 41.

4. “The Unpopular Mr. Lincoln,”

Larry Tagg, Savas Beatie; 2009. p. 365.

5. “Abraham Lincoln, Speeches

and Writings;” Library of America,

1989. p. 454, Lincoln to Erastus Corning and Others, June 12,

1863.

6. “Franklin’s

Crossing, June 1863”; & “Third

Fredericksburg,” part 2; Noel Harrison; articles on

the blog, “Mysteries & Conundrums” August 1,

2011 &

September 9, 2013 respectively.

7. “Abraham Lincoln,

Speeches

and Writings;” Library of America,

1989. p. 451-2, Lincoln to Hooker, June 5,

1863.

OTHER SOURCES:

The Civil War Day by Day, An Almanac 1861

– 1865; E.B. Long with

Barbara Long; Da Capo, 1971.

Hooker's actions between June 5 &

10 relly upon Noel Harrison's articles referenced in note #

6.

What's On This Page

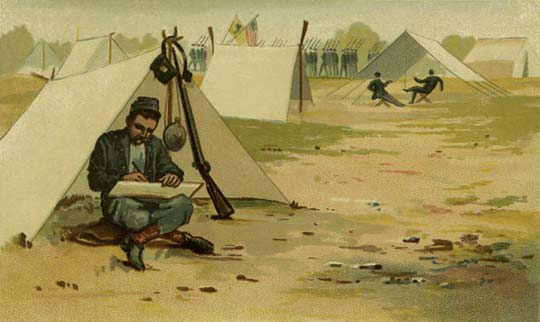

Considering the hullaballoo at Headquarters, Washington, and elsewhere, things were very quiet in the camp of the '13th Mass.' at this time. The return to camp life brought the usual return to picket duty, guard duty, inspections and drills. Most of the soldiers' letters and diaries throughout this page comment on the same. Sergeant George Hill opens the page with a letter expressing his disappointment with Hooker just after the retreat from Chancellorsville. Charles Davis summarizes the return to camp life whille a new campaign is planned. Soldiers record the weather turned hot. Warren Freeman & Edwin Field describe the new camp site. Field also comments on the departure of the two years and 9 mos men, and, Governor Andrew of Massachusetts, is raising another Black Regiment, the '55th', in which some members of the 13th were appointed officers. Feeling qualified for an officer's commission himself, he laments the influence required to obtain one. The Review by Gen.Reynolds, May 30, is recorded by Sam Webster and John Bowdwin in their diaries, but no details are given. Politicians investigating the latest military debacle of Chancellorsville visited camp and Charles Adams writes that Senator Henry Wilson of Natick visits the Company H boys from his hometown. Major J. P. Gould prepares to leave the regiment for special duty in Boston, and makes a noble speech that gets picked up in the papers. Warren Freeman gives a number to the men left in the regiment and his company. He also notes the 6th Corps has once again crossed the river. Sam Webster climbs a tree to see what is going on the other side. The frequent orders to march are recorded by Boudwin. The page ends with the incredible 'must-read' memoir of John S. Fay who was struck by a shell April 30. His field hospital was abandoned when the army moved north in June. It was captured by Rebels and Fay, recovering from two amputations was sent with others, to Libby Prison in Richmond. Surgeon Allston W. Whitney of the 13th figures prominently in the story. He describes his ordeal in detail.

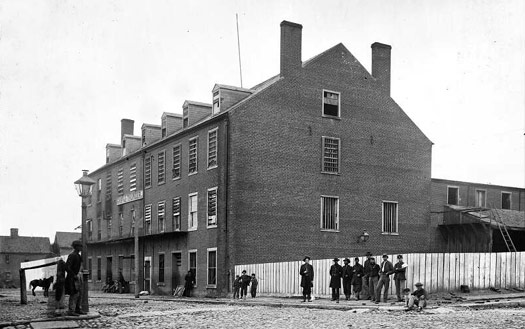

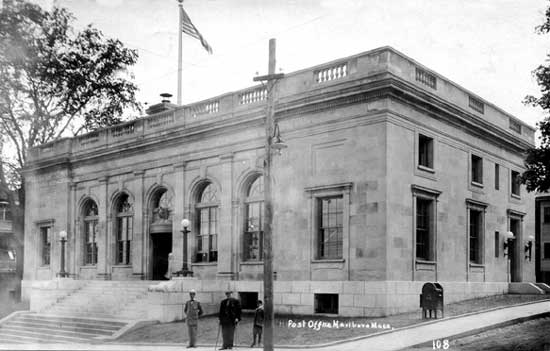

PICTURE CREDITS: All images & Maps are from the Library of Congress digital images collection, with the following exceptions: General Hooker and Staff is from the NY Public Library Digital Collections; Howard Pyle's, "The Charge," 1904, from "History and Romance, Works by Howard Pyle From the Brokaw Family Collection"; Brandywine River Museum, 1998; Captain Pierce's kepi is from the "Echoes of Glory" series of Time-Life Books, p. 178; (photo taken by Larry Sherer, assisted by Andrew Patilla); Captain Joe Cary & Priv. Chandler Robbins, are from the Army Heritage Education Center's Civil War Photograph Collection, (Carlisle, PA) photographed by Brad Forbush; Major Gould, and Sergeant Sigourney Wales, are also from Carlisle, Mass MOLLUS collection; Private Edwin Field from Scott Hann; Charles N. W. Cunningham & Charly Drew, both of Company A, from Tim Sewell; Libby Prison, Elizabeth Van Lew, and Richard Turner from Mike Gorman's website "Civil War Richmond;" www.mdgorman.com; The Marlboro, Mass., Post Office from the Marlboro Historical Society; ALL IMAGES have been edited in photoshop.

Back In Camp May 9 - 17

Letter of George Henry Hill, May 9th 1863

On May 5th a tired but confident soldier, George Hill, wrote from the battlefield trenches:

"Thus far everything is in our favor and we have confidence that we are to win this fight in such a manner as will allow no doubt of it. ...I shall not send this to day and possibly may have something to add."

A few days later, now, obviously dejected, George finished his letter.

Friday May 9

Again we have retreated, To continue the account where I left it. We remained in our trenches until Wednesday night when we recrossed the river and we are now camped about 6 miles below Falmouth. Where we go next of course I cannot tell. I am

(7)

disappointed enough for I was so confident of success. I have still every confidence in Hooker but he was a little too ambitious. The enemy suffered much more than we did in killed and wounded and if Sedgwick had held the Heights of Fredericksburg our victory would have been complete. Wednesday a terrific storm came on but whether that or some movements of the enemy caused our return to this side I know not.

I have not seen a paper for a fortnight. I am anxious to know what is going on in other parts of the country. God grant that something is being accomplished.

I am well but pretty much

(8)

played out, for until last night I have not had a full nights sleep for 11 days.

Love to all.

I will write again as soon as anything occurs.

Excuse Haste fromAfffc Son

Geo H

George is correct about Sedgwick holding the Heights of Fredericksburg, and the thought may have occurred to General Sedgwick at some point, but he was under orders from Hooker to make haste towards Chancellorsville. Hooker did nothing to help out Sedgwic's troops when they were attacked by the enemy in force at Salem Church. The faillure of the campaign, although George Hill could not have known it when he wrote this, was with General Hooker, who lost his resolve in mid-campaign.

The following narrative is taken from the regimental history, "Three Years in the Army," by Charles E. Davis, Jr.; Boston, Estes & Lauriat; 1894. (p 211 - 212).

We remained in camp in this vicinity until June 12. During this time the regiment was engaged in the usual camp routine of drills, reviews, inspection, and parades, beside doing our share of the picket duty along the north bank of the Rappahannock River, the enemy’s pickets being on the south bank, within easy hearing distance.

On the 21st of May the regiment was transferred from the third to the second brigade* in the same division under command of General Robinson ; General Reynolds continuing in command of the First Army Corps. Our associates in the second brigade were the One Hundred and Fourth New York, the Sixteenth Maine, and the One Hundred and Seventh Pennsylvania regiments. The Eleventh Pennsylvania was subsequently transferred to the same brigade, to our very great pleasure.

All this time active preparations were being made for another campaign, while we freely discussed the competency of generals, planned campaigns, and patiently waited for an order from Washington to take command of the army. As time rolled on, and the price of recruits advanced, we learned that the Government felt that we were doing too good a service in the ranks to be transferred to the head of an army. The wishes of the Government were not to be lightly set aside, so we continued to tote a knapsack and gun, though we yearned occasionally for the comfortable quarters of a major-general.

So much complaint was made about carrying out the order of March 21st, respecting the wearing of badges, that on the 12th of May General Hooker issued an order containing the following paragraphs:

"The badges worn by the troops, when lost or torn off, must be immediately replaced. Provost marshals will arrest as stragglers all other troops (but those designated as being without badges) found without badges, and return them to their commander under guard."

From this time on the corps

badge was universally worn, and

proved a great convenience, besides exciting a feeling of pride among

the men.

From this time on the corps

badge was universally worn, and

proved a great convenience, besides exciting a feeling of pride among

the men.

From time to time fears were entertained at headquarters that the enemy were intending to cross the river, and orders were received to move, but were countermanded in season to prevent us from marching.

We received about this time a lot of books and pamphlets from home, collected by some kind friends who were not forgetful of our wants. They afforded us a good deal of pleasure, and helped to wear away the depression that we shared in common with the rest of the army at our recent defeats.

[Pictured is the kepi of Captain Elliot C. Pierce of the '13th Mass.' Recently commissioned captain to the Ambulance Corps of the First Army, his circular badge is red, white & blue, representing the 3 Divisions of the First Corps. - "From Echoes of Glory, Arms & Equipment of the Union;" Time-Life Books].

*NOTE: Davis has made a mistake, the Regiment was transferred to the First Brigade, of General Robinson's Second Division.

Diary of Sergeant John Boudwin, Company A

From

the

collection of the Pearce Museum, Navarro College, Texas.

John Boudwin's diary continues to

chronicle the

routine of camp life.

May 8. Cloudy. Cleaned our rifles and clothes and they were in need very much. Laid in the woods all day.

May 9. Pleasant. Had Inspection of arms & equipment. Received rations of Beans Coffee & Sugar.

Sunday,

May

10.

Pleasant. Have

our regular Sunday Inspection of

arms and Clothing.

May 11. Very warm. Went down to brook and had a good Bath. Eve. Dress Parade.

May 12. Pleasant & Very Warm. Company Drill in the morning. Eve. Dress Parade.

May

13.

Pleasant.

The regiment went on

picket. Eve. shower of rain.

May

13.

Pleasant.

The regiment went on

picket. Eve. shower of rain.

May 14. Pleasant. Drew Clothing. Afternoon Heavy shower.

May 15. Pleasant. At 3/30 Was woke up from our peacefull slumbers by the orders to march. Cooked some coffee and at 6 AM the order was countermanded. After noon Capt Cary [pictured]* from Boston arrived in Camp looking well.

May 16. Pleasant. At 6 AM we went out to drill and stayed till 8. I drilled the Company in the Bayonet Excercise. Afternoon went down and had a bath with Mess Mate Charly Cunningham. Had dress parade and a very poor one under Major Gould.

Sunday,

May

17.

Pleasant.

Had Regimental Instruction. Dress Parade

finished the days work.

NOTE: *Captain Joe Cary of Company B, was granted a 20 day leave of absence December 20th, 1862. This was extended another 30 days in January, 1863. Cary was reported invalided in Boston from the result of chronic dysentery. He mustered out of the service Feb. 28, 1863. The Custom House in Boston where Cary was now employed, provided jobs for many of Boston's veterans after their service. The objective of his visit to the regiment is unknown, but his two brothers William & Sam, were still active officers in the '13th Mass." William was Captain of Co. G at this time, and Sam, 2nd Lt., Co. F.

Return to Top of Page

Change of Camp; Change of Brigade

Letter of Warren Freeman, Company A

Warren's letters were published privately by his father in 1871; "Letters From Two Brothers Serving in the War for the Union;" Riverside, Cambridge: Printed by H. O. Houghton and Company.

In Camp Near Fitz-Hugh Mansion, Va., May 18, 1863.

Dear Father, - I am in receipt of none of your favors since I received yours of May 2nd. I do not know the reason, but suppose they may be detained on the road; I shall expect one or two letters from home in to-night’s mails sure. I have recently received a letter from Aunt Hettie, dated Madison, May 4th; she and Uncle Samuel are well.

We

now have a nice camp in a pine grove, which makes it quite

pleasant ; there is a brook of good water running near by, where we

frequently bathe. There is not so much prospect of a move as

there was the first day or two after we got here, although I suppose we

shall get routed out of these cozy quarters on some fine morning when

we least expect it. The following is the order of the day at

this

present writing : roll call at four o’clock A.M. ;

sick –

call at five o’clock ; breakfast at half-past five o’clock ; then drill

from six to eight o’clock ; then we have nothing to do till four

o’clock P.M. (unless it is fatigue work), when we drill for two hours,

and finish with dress parade.

We

now have a nice camp in a pine grove, which makes it quite

pleasant ; there is a brook of good water running near by, where we

frequently bathe. There is not so much prospect of a move as

there was the first day or two after we got here, although I suppose we

shall get routed out of these cozy quarters on some fine morning when

we least expect it. The following is the order of the day at

this

present writing : roll call at four o’clock A.M. ;

sick –

call at five o’clock ; breakfast at half-past five o’clock ; then drill

from six to eight o’clock ; then we have nothing to do till four

o’clock P.M. (unless it is fatigue work), when we drill for two hours,

and finish with dress parade.

I made a visit to Porter’s Battery the other day, and saw the West Cambridge boys, - Sergeant James Kenny, Dan Benham, Fred Bloxham, and Bill White ; they are all well, fat and hearty ; Kenny had his horse killed at the storming of the heights in the rear of Fredericksburg ; they are in Sedgwick’s Sixth Army Corps, and, you will recollect, they saw hard fighting in the late battles. By the way I should like to write you a full account of the week’s fighting at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville (or what I saw of it), but then you have had so much better accounts of it from those whose vocation it is to use the pen, that I apprehend I could not produce anything readable. Carleton, of the “Journal,” is the best and most reliable of all the army correspondents that I am acquainted with.*

I think General Hooker has gone to work the nearest right of any general we have yet had, and if he could have the cooperation of the other generals, victorious results would follow; but it does seem as if we could never do anything in concert.

All of our ambulances have been over the river to get the wounded ; they lay on the field for two nights and one day without care ; those that are wounded the most severely of course were dead ; about 1,000 of our poor fellows were brought over. I am told by one of our ambulance drivers that the rebels offered fabulous prices for boots, watches, pipes, etc., and offered to pay in greenbacks, of which they seemed to have a plenty.

Our papers speak about the prisoners that we take as looking half-starved, ragged, etc. Now I could never see this. Those that I saw, and I should think there were 2,000 of them, were fully equal in looks and condition to the average of our men ; they say we can never subdue them, that they will fight till there is not a man left. Their gray uniforms give them a kind of dirty appearance, and they nearly all wore felt hats, but some of them had on very neat and handsome uniforms. They lost heavily in the late battles, especially in officers, the most prominent of whom was Stonewall Jackson.

I am well, and enjoying myself here in camp first-rate. In writing please inclose a little black pepper, or send some in a paper occasionally, it comes right handy when the sutler is not round.

I should have mentioned before that some of our forces are placing big guns and mortars in position, on the heights this side of the river ; they are going to try Johnny Reb with Dutch ovens soon, I believe.

Warren.

*Carleton of the Boston Journal is Charles Carleton Coffin.

The Journal published 'Stories of Our Soldiers' in 1893,

edited by Carleton.

Diary of Sergeant John Boudwin, Company A

From the collection of the Pearce Museum, Navarro College, Texas.

May 18. Pleasant. On guard with Corporal & 15 men. Brigade Inspection of arms & Equipment. Noon, orders to move camp at 4 PM. Moved 1/4 mile to a large field and pitched camp. Dress Parade in the eve.

May 19.

Pleasant. Afternoon

Battalion drill by Captain

Palmer.

Dress Parade in the eve. 2 new Sergeants made (Drew

and Cunningham) and 2 Corporals (Putnam & Hebard). [Pictured at right, Charles

N. W. Cunningham, John's messmate, Company A*].

May 19.

Pleasant. Afternoon

Battalion drill by Captain

Palmer.

Dress Parade in the eve. 2 new Sergeants made (Drew

and Cunningham) and 2 Corporals (Putnam & Hebard). [Pictured at right, Charles

N. W. Cunningham, John's messmate, Company A*].

May 20. Pleasant. Company Drill by Lieut Kimball. He was taken sick and I resumed the drilling. At Noon the whole regiment was detailed to clear up a new piece of ground for a camp. Our regt is going in to the first Brigade and is to be under command of Col Leonard. The Division has only 2 Brigades.

May 21. Pleasant. Day was very warm. Fixed up camp in good style. Dress Parade in the eve.

May 22. Warm & Sultry. No drills today, all are busy fixing up camp.

May 23. Warm & Sultry We are busy fixing arches in front of tents &c. Cleaning up for Sundays inspection of arms &c. Battalion Drill in the afternoon. Dress Parade in the eve.

Sunday,

May 24.

Warm & Sultry. Had

Inspection in the Morning. News of Vicksburg being taken.**

Had a dress parade.

May 25. Cool & cloudy. At 9 AM the regt went on picket..

May 26. Cool cloudy. Brigade Guard Mounting in front of Hd Qrs.

*The roster states, Charles N. W. Cunningham; age 18; born, Cleveland, Ohio; druggist, mustered in as priv., Co. A, July 16, 1861; mustered out, October 5, 1863; commissioned in the regular army, and became a captain by promotion; died in Texas, March 9, 1893.

**At this time General Ulysses Grant was trying to take Vicksburg by direct assault. An attack on May 19 failed. An all out bloody assault on May 22 had some breakthroughs but counter-attacks closed the breaches. Strong Rebel fortifications beat back the assault. There were 3,199 Union casualties. (from Civil War Almanac by E.B. Long & Barbara Long, Da Capo Press, 1971).

Diary of Sam Webster, Company D, (drum corps)

Excerpts of this diary (HM 48531) are used with permission from The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA

Thursday, May 21st, 1863

Regiment transferred to 1st

Brigade of 2nd Division instead of 3rd Brigade. Col. Leonard

being Senior Supersides, Col. Root of the 84th N.Y. in command of the

brigade which contains 94th and 104th

N.Y., 16th Maine, 107

Pennsylvania, and 13th Mass. Water fair.

Have moved camp towards White Oak Church - tho' it is still

a

mile or more off - the 6th corps lie nearer to it.

Letters Home; Edwin Field and Charles Adams

Letter of Edwin Field, Company B

Edwin Field of Chelsea, Mass., with a few school friends including Charles Leland, enlisted in the 4th Battalion of Rifles at the outbreak of the war. Edwin was killed at Gettysburg. His parents filed for a pension. To prove their dependence on young Edwin's income from soldiering, the parents presented the government pension agent with 11 or 12 copies of Edwin's war time letters. All the letters were written around pay-day. The letters remain today, in Edwin's Pension File at the National Archives. Noted Gettysburg historian, Timothy Smith shared a copy of the file with me. This is the last of Edwin's pension file letters. Eventually they will all be transcribed and posted on the website.

In

the letter Field makes reference to his comrades who gained commissions

in the 55th Massachusetts Infantry. This was the 2nd

'Colored'

Infantry unit organized by Governor John A. Andrew. When he

put

out the word that Massachusetts was going to organize a 'Colored'

regiment, so many men responded, from Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania and

Virginia, that there were men left over after the ranks of the '54th

Mass.' were full. Governor Andrew decided to organize another

regiment with the men left over, and the 55th Mass.' was born.

To

be an officer in one of these regiments, there were a couple

requirements. The candidate had to ve a veteran with field

experience, and have abolitionist sympathies. Several men of

the

13th became officers in the 55th.

Camp near White Oak Church Va.

May 24th /63

My Dear Sister

I received your letter of the 12th last week & was very glad to hear that the money I sent arrived home safe I had not heard from you for nearly three weeks & I began to feel a little anxious to hear from home I always feel so when any length of time has elapsed without hearing from you. You have no idea how much good a letter does me from home to hear that Father & Mother are well even if there is not any particular news in it I read it with full as much interest the longer I stay out here the more eager I am to hear from home.

I know how it is with you, you must get very tired with your school duties & of course you do not feel much like writing letters after the duties of the day are over.

We have been encamped in this place nearly ten days & expect to remain some time longer the fact is, we can not make a movement the army has been greatly decreased nearly all the nine months & two years have been mustered out I do not know but we shall have to remain in camp all summer unless they hurry the Conscripts out which I hope will be done & that immediately

We are pleasantly situated here although out in the open field all the troops are out in the open field by order of Hooker they say it is much more healthy we have trimed up our camp very nicely with cedar trees front of every tent arbors are built and the tents are set up from the ground by means of crotches & small poles it gives the camp a very fine appearance nearly all the troops around hear have trimed up the same way We have very good water & plenty of it & we use a great deal of it to I can tell you for we are having extremely hot weather now & have had for the last week we have but little drilling to do our Regt. numbers two hundred & fifty men for duty our Co. numbers twenty six men for duty Col. Leonard is in command of the brigade & Lt. Col. Batchelder commands the regt. our old Capt. Cary was in camp last week he is in the Custom house in Boston I asked him if he knew Unckle Spencer he said he did not he is looking finely & appeared very glad to see the members of his Co.

I received a letter from Helen

Kelly last week she said she

had been stopping with you for short time she says she has to study

very hard as her lessons are long and difficult

I received a letter from Helen

Kelly last week she said she

had been stopping with you for short time she says she has to study

very hard as her lessons are long and difficult

I was very glad to hear that Fred Hills arrived home safe I suppose he thinks he has seen some of the hard ships of war but he ought to go through one campaign in Va. if he wants to see hardship I am expecting to receive a letter from him every day

I understand that Gov. Andrew has organized another Colored regt. called the 55th some of the members of this regt. have got commissions in that unit. Lt. Fox has been appointed Major & Sgt Wales [pictured] has been appointed Capt. I would not care if [I] had a commission myself I feel myself fully competent to hold one but it requires a great deal of influence to get one[?] & a great many colors[??] waving [?]

Send my love to Father & Mother remember me to all

inquiring friends

Your affc – Brother

Edwin

Write Soon

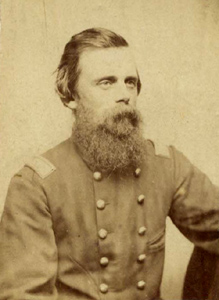

Sergeant Wales record in the roster reads as follows: SIGOURNEY WALES; age, 25; born, Boston; clerk; mustered in as sergt., Co. C, July 16, '6l; mustered out as 1st lieut., May 28, '63; was promoted to capt., in the 55th Mass.; residence, 22 Hadley St., N. Cambridge, Mass. -- He is listed as a Major of the 55th Mass., on the notes for this image.

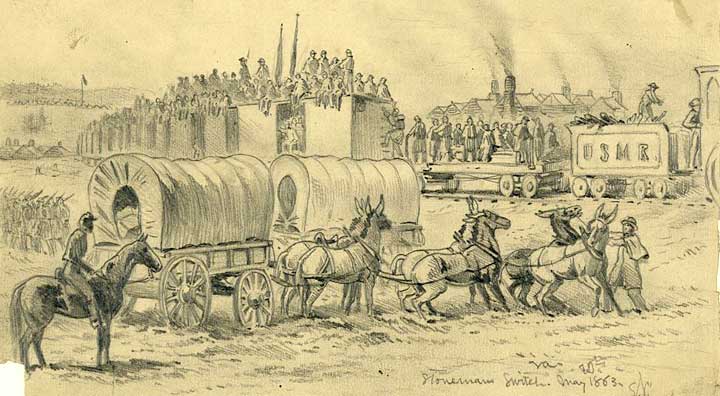

Another great sketch from Edwin Forbes (although tattered around the edges) depicting the departure of troops at Stoneman's Switch, dated May 20th 1863. Hooker had to get his Chancellorsville Campaign underway before enlistment time was up for thousands of "2 years" troops. They are seen here boarding the train to begin their journies home.

Letter of Charles Adams, Company A

Charles Adams to Dear Sister, 26 May, 1863; Charles Adams Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society. Used with permission.

Camp near White Oak Church Va.

May 26th 1863.

Dear Sister

As I have

a few spare moments

this morning, I thought I would answer your letter of the

17th, which I

received a few days ago.

The majority of the regiment went on picket yesterday morning, to be gone for two days, but as I was on camp guard I was not obliged to go, so I am keeping house all alone in my glory. I received Ira’s letter a few days ago after yours & have already answered it.

P2

I suppose you all read it at home. He had so much to say about “Heavenly things,” that he did not even mention what he was doing, or anything else. I was sitting in my tent the other day, when I heard somebody inquiring where my tent was, and on going out who should I see but Henry Bird, who used to be in Ebenezer Clapp’s Store.

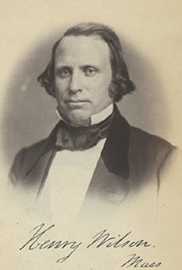

We had quite a long talk about old times &c. He is in the 62 N. York Reg.mt & is now a corporal in Co D. His Regmt is in Sedgewicks Corps (6th) which stormed the Heights of Fredericksburg in the last battle, & is encamped about two or three miles from us. He had a list of Dorchester boys who had enlisted, their Regmt & companys which Clifton Phipps had sent him, so he had hunted me up without trouble. He says he enjoys excellent health, &c and is coming over to see me again. Hon Henry Wilson was here a few days ago.

P3

There

is a company in this regiment from

his native town (Natick, Mass.)* I suppose John told you

about

Abijah Jenkins who is in this regiment. He said he was

acquainted

with you & John. He is one of the color Corporals (or

guard). He wished to be remembered to you

both.

There is a

Stoneham Company in this regiment & I think likely that you

know more

of them.** There has been considerable excitement

here, the

last

few days, occasioned by the success of Grants Army in the

West. It was read on dress parade and as it has not

been

contradicted, I suppose it is true. By the way,

have you

learnt

any new songs lately ? I have if you have not, and I may

call

round some night & serenade you.

There

is a company in this regiment from

his native town (Natick, Mass.)* I suppose John told you

about

Abijah Jenkins who is in this regiment. He said he was

acquainted

with you & John. He is one of the color Corporals (or

guard). He wished to be remembered to you

both.

There is a

Stoneham Company in this regiment & I think likely that you

know more

of them.** There has been considerable excitement

here, the

last

few days, occasioned by the success of Grants Army in the

West. It was read on dress parade and as it has not

been

contradicted, I suppose it is true. By the way,

have you

learnt

any new songs lately ? I have if you have not, and I may

call

round some night & serenade you.

I have not heard from Mary Ann for a long time, but as I wrote last I shall expect an answer before I write again. Tell George to inclose $1.00 of stamps when he writes again

P4

as I have only six left of those he sent last. I would like 10, one cent stamps & the rest three’s. I hear occasionally from W. Clapp & Johnny Robinson, also from Clifton Phipps, Wallace & some others so I have my hands full to answer them all. As my stock of writing matter is about played out & I am ditto, I think I had better close & get dinner. I shall expect a good long letter from you very soon, so you know what to expect. Love to all the folks, and inquirers,

From Your

Brother

Chas. F. Adams

I

have just rec’d a letter from Johnny

Robinson. His vessel is

to

convoy a ship from N. York bound to California.

They are to

accompany her till she strikes the S East trade winds 5 or 6 degrees

south of the equator & then will return & be discharged.

He

sends

his respects to all the Dorchester folks.

C.F.A.

NOTES

*Senator Henry Wilson of Natick, Mass, a

tireless supporter of the cause of the Union and abolition of

slavery, frequently visited

Massachusetts troops to look after their needs. Company H was

organized in Natick.

** Company G was organized in Stoneham.

Illustration by Louis K. Harlow

Major Gould's Speech & General Reynold's Review

Diary of Sergeant John Boudwin

From the collection of the Pearce Museum, Navarro College, Texas.

May 27 Cool & Cloudy. Brigade Guard Mounting at 10 AM The Regiment came in from picket. Received orders at noon to hold ourselves in readyness to march at a moments notice. At 1PM the order was countermanded. Had a dress parade in the eve. Major Gould made a speech and declined the present the boys were going to make him and said the money would be put to as good use by sending it to some Bank in Boston for the Benefit of Disabled Men of the regt. And he made an addition of $50 to it.

Roxbury City Gazette, June 13, 1863

The speech of Major Gould made its way into one of the Hometown Newspapers in June. Here is a full account from the Roxbury City Gazette. The following was downloaded from the currently dormant website "Letters of the Civil War" by Tom Haynes.

THIRTEENTH MASSACHUSETTS.

JUNE 13, 1863.

A Self-Denying Soldier.

Our old friend Major J. Parker Gould, of Stoneham, of the 13th Mass. Regiment, who has gallantly led his command in several hard fought battles and is deservedly popular with his men, has declined to accept the horse and equipments which they intended to present to him and for which they raised by subscription the sum of $500.00 on their last pay day. In his letter declining the handsome testimonial, the Major uses the following noble language:-

“But circumstances make this inopportune for the reception of the presents. A more favorable time will occur for the interchange of testimonials. We have been several times engaged in battle with the enemy. These engagements have much reduced our rank and file. Many a noble comrade in arms has found a grave on the field of battle, while many others, as noble, have returned home disabled for the remainder of their life. Their friends are thereby deprived of the support and the many enjoyments they would otherwise have received from the manly hands of those who left homes two years ago on their patriotic mission. We are still in the field. We have yet one third of our time to serve. Your valor may again and again be tested in battle. We must learn the future from the past, and be admonished by it. I could hope that every member of the regiment, Providence so ordaining it, should return to his home. But I fear a more honorable mission awaits some whom I now address, on some memorable battlefield, whose loss, their friend will have to mourn when they proudly reflect upon your fearless heroism; while the only joy of others in their life-long maimed condition, may be their consciousness of faithful duty performed in the field. Those who may be permitted to return home will receive the gratitude of a loyal people and enjoy the admiration of their friends. Those who should reap a soldier’s honors here, will leave to their heirs a rich legacy of patriotism and honor.

With these considerations, gentlemen, I most respectfully decline the testimonial designed me. I have, however, this proposition to submit to you, that the sum now raised be placed on deposit in some institution in Boston, subject to supervisors of our own selection, under whose direction it will be expended for the benefit of such members of the Thirteenth Regiment as become disabled in the service, or for the benefit for the families of such as have been or may be killed in battle, or die in the service. Should this proposition meet your approbation, I will add fifty dollars to that amount, to be expended in the same manner. And, gentlemen, though I decline the testimonial, let us trust that the same sentiments of mutual regard will continue to be enjoyed to the close of the service. With the highest respects for you as soldiers and men, accept my sincere thanks for the compliment tendered to me.

I

remain most

respectfully

and

truly, your friend,

J. P.

GOULD,

Major 13th

Regt.

Mass.

Vols.

(Roxbury City Gazette; June 11, 1863; pg. 2, col. 3.)

Major Gould was detailed for detached duty, July 1st, and departed sometime around then for Boston, where he was initially sent to supervise the conscripts drafted for the regiment. He did Provost Marshal duty on Long Island in Boston.

Diary of John Boudwin, continued.

From the collection of the Pearce Museum, Navarro College, Texas.

May

28.

Pleasant.

Brigade

Guard Mounting. No drills to day.

Dress Parade. One of Co. K court-martialled

& fined $3 for Improper Conduct.

May

28.

Pleasant.

Brigade

Guard Mounting. No drills to day.

Dress Parade. One of Co. K court-martialled

& fined $3 for Improper Conduct.

May 29. Pleasant. Morning Drill in skirmishing. Afternoon Battalion Drill. Eve. Dress Parade.

May 30. Pleasant. At 5 AM marched 1 mile towards White Oak Church to be reviewed by Gen Reynolds and staff. We appeared in white gloves and looked well. Dress Parade

Sunday,

May 31.

Pleasant. At 6 Am Regimental

Inspection by Lt. Col. Batchelder. Afternoon paymaster

arrived and received my pay up to May 1st.

Diary of Sam Webster

Excerpts of this diary (HM 48531) are used with permission from The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA

Saturday,

May 30th, 1863

Corps

review by Gen. Reynolds at 7 in the morning. Very fine.

Have fixed

up a tent with canvas sides, double

length beds

at one side, feet together, heads toward ends. Sawyer and I

at

one end. Ike and Libby at the other. Have our beds

raised on pole slats and pine tree "feathers." Weather

exceedingly warm. Tents screened as well as ornamented by

pine and cedar trees. The camps of the 3rd Division are very

nicely fixed in the same manner. 3rd Divison are

mostly new Regiments who relieved the Pennsylvania Reserves.

They are all Pennsylvania troops. The Brigades,

Divison and Corps are all desingated by badges, flags and colors, by

which they are very easily distinguished.

Have fixed

up a tent with canvas sides, double

length beds

at one side, feet together, heads toward ends. Sawyer and I

at

one end. Ike and Libby at the other. Have our beds

raised on pole slats and pine tree "feathers." Weather

exceedingly warm. Tents screened as well as ornamented by

pine and cedar trees. The camps of the 3rd Division are very

nicely fixed in the same manner. 3rd Divison are

mostly new Regiments who relieved the Pennsylvania Reserves.

They are all Pennsylvania troops. The Brigades,

Divison and Corps are all desingated by badges, flags and colors, by

which they are very easily distinguished.

JUNE,

1863

Philadelphia Inquirer, June 8, 1863

PHILADELPHIA INQUIRER

June 8, 1863

General

Robinson’s Division.

Among the regiments composing this truly splendid division are several from Pennsylvania. Although not in numbers as strong as some others are, nevertheless this division is not excelled in point of discipline and efficiency by any in the service. Their commander, General Robinson, is ever modest, quiet and unobtrusive in demeanor, a true soldier, knows well his duty and does not in any manner shrink from performing it; brave and gallant upon the field and possessed of administrative abilities not excelled by any.

The spot selected as the encampment of this division is among the shadiest and coolest in our whole encampment. Several springs of cool and delicious water are within its boundaries, while so well and faithfully are its police duties performed, that the grounds and its surroundings are kept neat and tasty.

One of the

peculiar

as well

as admirable traits of the

troops comprising this division consists in the fact that the houses

and

property of the residents near where it is located, whether Union or

“Secesh,”

are never in any way disturbed or molested, everything remaining in the

same

order as left by their decamping owners.

One of the

peculiar

as well

as admirable traits of the

troops comprising this division consists in the fact that the houses

and

property of the residents near where it is located, whether Union or

“Secesh,”

are never in any way disturbed or molested, everything remaining in the

same

order as left by their decamping owners.

The following named gentlemen are members of the gallant General’s staff: –– Lieut. Morgan, of Eighty-sixth New York, Assistant Adjutant-General; Lieut. Bralton, of One-hundred-and-fourteenth Pennsylvania Volunteers, Aid; Capt. [Charles] Hovey, of Thirteenth Massachusetts, Inspector-General; Capt. Mason, Assistant Quartermaster; Capt. Fred Gerker, of your city, Commissary; Lieut. [Melvin H.] Smith, Thirteenth Massachusetts, Ordnance Officer; Assistant Surgeon Nordquist; while the amiable and skilled Dr. Whitney, of the Thirteenth Massachusetts, is the Medical Director.

NOTE: That's Ordnance Officer Melvin H. Smith, top, and Inspector General Hovey, bottom, both of the 13th Mass. Also - I believe the newspaper is wrong, Lt. Morgan was in 88th NY & Lt. Bralton in the 104th PA.

From the collection of the Pearce Museum, Navarro College, Texas.

June 1. Pleasant. Company Drill. Batallion drill by Lt Col Batchelder. The day was very warm and dusty. Dress parade in the evening by Col Batchelder.

June

2

Pleasant & warm. The regiment was on picket.

Sergt

C from

our company Grand Guard Mounting of picket and Camp Guard.

Went down to

brook and had a good bath my self and Charley Drew [pictured at right, Sgt. Charles

A. Drew*].

June

2

Pleasant & warm. The regiment was on picket.

Sergt

C from

our company Grand Guard Mounting of picket and Camp Guard.

Went down to

brook and had a good bath my self and Charley Drew [pictured at right, Sgt. Charles

A. Drew*].

June 3. Pleasant. Orders to March and countermanded again. The regiment came in from Picket. No drills. Battallion drill in the afternoon, dress parade in the Evening.

June 4. Pleasant Morning. Company drill, afternoon Brigade drill by Col Leonard. Evening dress parade. Orders read to hold ourselves ready to march at Short notice. Evening at 9 PM orders to March at daylight.

June 6 Pleasant. At 2 a.m. the long roll was beat and we got up and cooked Breakfast. At day break struck tents and formed in line and stacked arms and laid-around camp all day. No orders came for us to start. At sunset pitched tents on our old ground. report that our forces 6th Corps across the river. Not many rebels over on the other side of the river as all firing was done by our side. At last a shower of rain and it was very much needed.

Sunday,

June 7.

Pleasant.

Inspection by Major Gould.

Nothing ocurred during the day. Evening dress

parade

*The roster states, Charles A. Drew, age 21; born, Boston; clerk; mustered in as priv., Co A, July 20, 1861; mustered out as sergt., August 1, 1864; residence, Northfield, Minn.

Letter of Warren Freeman, Company A.

Near White Oak Church, Va., June 7, 1863.

Dear Father, - There is no particular news in camp to-day. Part of the Sixth Corps crossed the river day before yesterday. On Thursday morning last, at daylight, we were routed out and ordered to pack up our duds and strike tents; soon after fell into line and stacked arms, then in the middle of the forenoon were told to pitch our tents and make ourselves comfortable. We had a brigade drill in the afternoon at four o'clock, and had the pleasure of turning out and packing up and striking tents again. Towards night it looked like rain, so we pitched our tents; shortly after we had quite a thunder-shower, the first rain we have had in sufficient quantity to lay the dust for three weeks. The dust is very annoying; it sifts into our tents and keeps us constantly dirty.

We have just finished our Sunday Inspection. We do not have religious services now, Chaplain Gaylord having left us.*

Our company has had in all about 130 men since we have been in the service; we now report twenty-six men for duty. Some of our absent comrades have been killed in battle, many more were wounded and carried to hospitals to die or be sent home; some have been promoted, several are on detached service, and a few have deserted. We number in the regiment 280 men for duty.

Warren.

*Chaplain Gaylord left the regiment March 12th, 1863, to accept a position of post-chaplain at Campbell Hospital, Washington, D.C.

Diary of John Boudwin, Continued.

From the collection of the Pearce Museum, Navarro College, Texas.

June 8. Pleasant. Morining drill. Everything quiet in camp. Afternoon Brigade drill by Col Leonard down to the river. Evening dress parade.

June 9. Pleasant. Morning drill. Took Company out and went through Company movements &c. Afternoon Batallion drill by Major Gould and Col Leonard. Evening Dress Parade.

[Colonel Leonard, pictured, right].

Diary of Sam Webster, Continued.

Excerpts of this diary (HM 48531) are used with permission from The Huntington Library, San Marino, CA

Monday, June 8th, 1863

Had a picture taken, and send it, with

one of Ike, [Sam's

Brother] to Uncle

George, today. The 6th Corps has been moved near

Fredericksburg. A lot of books arrived the other morning, as

we were packed up to march, and they got pretty well scattered.

I got hold of, and had nearly finished "Dred"

by Mrs. Stowe,

when I found there were two volumes, and I hadn't the second.

I found it, however, no one thinking a 2nd volume worth

carrying off. Yesterday while the Brigade drilled on a field

about a mile from and sloping toward the river, I mounted with a spy

glass into a tall pine. Found it very cool and nice swaying

in a comfortable seat to and fro in the breeze, but saw only a few

cavalry piquets, and deserted winter camps and a small earthwork on the

bank of the river. Guard-mounting with packed knapsacks is

the order of the day. Anything for work on a hot day -

officer's rule. Have also been over to the 12th Corps to see

Captain Tourison. His Co. is now the 147th Pa.

Both

he and his son (his Lieutenant) were wounded at Antietam, the Capt. in

the same place where he was hit while in Mexico. They lay

near Brooks

station. Our present method of messing proves very

agreeable. Sawyer is Brigade Drum Major; though some of the

other regiments - or their drummers - objected at first.

General Orders

No. 50

Headquarters

Second Division

First Army Corps,

June 10, 1863

1. Existing orders require a critical inspection of companies half an hour before dress parade, the object of which is to see that men are in a proper condition to go on parade, that the clothing and accoutrements are clean and in good order. At dress parde of ceremony, officers and men will be required to appear in uniform. Regimental commanders are reminded that white hats and butternut colored sacks form no part of the prescribed dress of a soldier, and must not be worn on parade. Soldiers will be allowed to wear them on fatigue. The practice of wearing boots or stockings outside of pantaloons must be suppressed on parade.

By command

of

GENERAL ROBINSON.

Diary of John Boudwin, Continued.

From the collection of the Pearce Museum, Navarro College, Texas.

June 10. Pleasant. Sergeant of Camp Guard to day. Regt. on picket at 12 noon. Orders came from picket to send out Camp Guard. I went out with the Men and acted as reserve. Up all night. Everything quiet along the line.

June 11. Pleasant, slight shower in the morning, sent out relief. News of the fall of Vicksburg from Corps Headquarters. Order to March in the morning of the 12th. At 12 midnight orders to march back to camp without delay.

The next day June 12, began the long, hard, hot & dusty march north in pursuit of General Lee's Confederate army.

"Libby Prison" by John S. Fay

Sergeant1John

S. Fay's wound

gave him the distinction of being the most severely

maimed

survivor of his regiment, and also the same of the

831 men

that served in the military from his hometown of

Marlboro,

Mass.

Sergeant1John

S. Fay's wound

gave him the distinction of being the most severely

maimed

survivor of his regiment, and also the same of the

831 men

that served in the military from his hometown of

Marlboro,

Mass.

A few versions of John Fay's story exist. The earliest is a hand-written account of his war time experiences created as part of his re-habilitation therapy - learning to write left handed. That document was donated to the Fredericksburg National Battlefield Park in 1996 by Mr. Peter Bolan, one of Fay's many descendants. Park Historian John Hennessy sent me a digitial copy of this. Also included were two typescript reminiscences; one of the Maryland Campaign and a later version of his Libby Prison experiences. The second reminiscence titled, 'Libby Prison,' appeared in the 13th Regiment Association Circular #23 in December, 1910. The two versions differ in detail. The following narrative is a combination of the un-edited 'earlier' version with occasional 'inserts' from the later version.

The date of his parole varies between July 14th & 16th, 1863. I believe it was the 14th. Fay was 23 years old when wounded. I've made a few spelling changes, but kept much of his idiosyncrasy in tact. Biographical information was compiled by Mr. Peter Bolan.

The captivity of Allston Waldo Whitney, Surgeon of the 13th Mass who operated on Fay, is recorded in the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion; SERIES II - VOLUME VI [S# 119]. He writes from Washington, November 27, 1863, "I arrived in this city yesterday after imprisonment of nearly five months as a prisoner of war in Libby Prison, Richmond, Va." - Brad Forbush, May 18, 2013.

Sam Webster, 13th Mass. Co. D, wrote the following in his diary the day after John Fay was wounded:

Friday, May 1st,

1863

Reported at Fitzhugh House, now used as First

Corps Hospital. Went out to the barn and

husked corn to get

filling for ticks. The boys have contributed about $250.00 to

Fay.

Memoirs of John S. Fay

On the 28th of April we was ordered to pack up and march. We left our camp about noon and marched seven miles and bivouacked for the night.

The next day we marched down to the Rappahannock river, near to the place where we crossed in December. The first division of our Corps [Wadsworth's Division] had laid a Pontoon Bridge, and crossed over and was in Line-of-Battle on the south side.

We was formed in line on the north side, in such a position that we could readily cross to the support of the first Division if necessary.

The Rebels had artillery in position on the hill about a mile and a quarter back from the river, from which they was trying to shell us, but they did not succeed in getting range of us.

It commenced

to rain in the

afternoon and continued to rain at intervals during the

night.

We lay in the same

position all night and

most of the next day. The

Rebels would

try to shell us every hour or two, but without effect, until about

three o’clock

in the afternoon when they succeeded in getting range upon us with a

battery of

twenty pound guns.  About

two o’clock a

dispatch was read to us from Gen Hooker stating that he had succeeded

in

crossing the river at United States Ford fourteen miles above

us with

the rest

of the army. We

now

knew that our

movement was only a feign to draw the rebels down the river from the

fords

above us. Gen

Hooker’s dispatch was

received with great cheering which so provoked the rebels that they

opened a

vigorous artillery fire upon us, and advanced their infantry and

commenced to

skirmish with the first division.

Our

division was in mass so if a shell fell among us it must hit somebody,

About

two o’clock a

dispatch was read to us from Gen Hooker stating that he had succeeded

in

crossing the river at United States Ford fourteen miles above

us with

the rest

of the army. We

now

knew that our

movement was only a feign to draw the rebels down the river from the

fords

above us. Gen

Hooker’s dispatch was

received with great cheering which so provoked the rebels that they

opened a

vigorous artillery fire upon us, and advanced their infantry and

commenced to

skirmish with the first division.

Our

division was in mass so if a shell fell among us it must hit somebody,

Several shells fell in other Regiments killing and wounding several men, when about fifteen minutes past five o’clock a shell fell among my Company, killing my Capt. George N. Bush and Second Lieut. Wm. Cordwell, and wounded myself, a piece of shell hit my right hand and right knee. At the time I was hit, I was lying on the ground resting upon my left elbow, my right leg bent, the foot resting on the ground my right hand resting [on my] right knee. A piece of shell passed through both hand and knee tearing my hand all to pieces and nearly severing my leg at the knee.

Soon after I

was wounded I was

packed up by Andrew J. Mann, and by him with the assistance of another

man, [Enoch C. Pierce,

pictured, above, right]2

was

carried to a house

about a mile in the rear that had been taken for a hospital.3

When they

was

carrying me to the hospital I was satisfied that my leg and arm would

have to

be amputated, after they got me there,

and the Doctors told me so I

requested

that Dr. A. W. Whitney of my Regiment should perform the

operation.

After waiting a

few minutes for him to get through with another patient that he was at

work

upon when they carried me in they

gave

me chloroform and that was the last that I knew until about half past

eight

when I came out of the effects of it and found my right hand and right

leg

amputated.

Acting hospital Steward S. E. Fuller [pictured, left] of my Co took care of me that night. in the night Col. Leonard came in to see me. The next day our Regt lay in line – of – battle in front of the hospital, and through the day nearly all the officers and men came in to see me. That night the Regt was ordered up the river with the rest of the Corps and crossed the river and marched to Chancellorsville and ... [there is a tear on the page here] ... battle was fought at that place in a ... [page is torn] ... afterwards. When our corps wer ordered off, the hospital, with about one hundred and fifty of us patients was left in charge of Dr. A. W. Whitney. This was a fortunate [thing] for me, for he was very interested in my case and he had the best of care taken of me. I am also greatly indebted to Acting hospital steward S. E. Fuller of my Co. and Chandler Robins of Co K of my Regt from Westboro, for the care they took of me. After the battle of Chancellorsville, and our army recrossed the river our Regt was encamped about a mile from the hospital and some of the officers or men came in to see me every day. I improved very fast and was considered

Out

of danger at the end of

four weeks. As

fast

as any of the patient[s] got well

enough so they could be move[d] without danger they was sent to

Washington. [Attentive

Hospital Steward Chandler Robbins of Westboro, Mass. pictured

at right.]

*******

Later version:

After my limbs were amputated by Dr. Whitney I was put into a front room on the lower floor of the house. The Pennsylvania boy was put into the same room.4 My intention was called to him by his movements, which indicated he was suffering intensely. The doctors first thought they could save his leg, but in the afternoon of the next day after we were wounded they told him they would have to amputate it.

It appeared that as soon as possible after he was wounded his captain sent word to the boy's mother, whose home was near Philadelphia, and she had telegraphed her son that she would be with him as soon as possible. In the evening of May 1, when the surgeon told him they would have to amputate his leg, he begged of them not to or at least to wait until his mother arrived.

The surgeon told him his mother could not come to him, for the War Department had issued strict orders to allow no one not connected with the army to go south of Washington. The boy replied, "Doctor, you don't know my mother. She has telegraphed me that she was coming, and she will come."

The surgeons decided to wait until morning before operating on him. They gave him opiates, so he was quiet nearly all night. I could not sleep. My bed was placed near one of the front windows, so I could look out on to the road that led up to the house. I spent the weary hours of the night watching that road, over which was much passing during the night.

In the morning soon after daylight I noticed an ambulance coming up the road. It drove up to the house and stopped, and to my surprise a woman alighted from it. She was met at the door by the assistant surgeon, who was on duty at that hour.

Soon he went over to Dr. Whitney's tent, which was pitched in front of the house. Dr. Whitney soon appeared. After a little delay he came with the woman into our room. I recalled the conversation I overheard early in the evening between the surgeon and the boy about the boy's mother. I knew she had arrived.

The surgeon went over to the

boy's bed to wake him. The

opiates had nearly spent their force. He soon rallied.

The doctor

motioned for the woman to come over to the bed and the poor

fellow caught sight of his mother. After a hurried kiss the mother

told the boy his leg would have to be amputated to save his

life.

The boy replied, "All right mother, if you say so."

The surgeon went over to the

boy's bed to wake him. The

opiates had nearly spent their force. He soon rallied.

The doctor

motioned for the woman to come over to the bed and the poor

fellow caught sight of his mother. After a hurried kiss the mother

told the boy his leg would have to be amputated to save his

life.

The boy replied, "All right mother, if you say so."

He was soon taken out of the room, the operation performed, and within an hour was brought back in an unconscious state. I learned afterwards that the surgeon did not expect he would ever come out from the influence of the ether. The doctor and the mother worked over him for a long time; finally they were rewarded by his coming to, but he was very weak; he had suffered so much from the wound before the amputation he was in a high fever and for more than a week his life was despaired of. It seemed as though that devoted mother never left his bedside; finally after seven or eight days he began to improve. Then the doctor commanded his mother to take some rest.

(Photo: A park historian from Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Park gives a rare presentation at the Henry Fitzhugh House near Fredericksburg circa 2011. The house is not on park land and is danger of being razed. It is currently owned by a developer. The picture was taken by Clint Schemmer of the Fredericksburg Star.)

As the boy improved, the mother began to take an interest in the three other badly wounded men that were in the room with him, of which I was one, so I had an opportunity to converse with her. I learned she was a widow; her wounded boy was her oldest child. He was but eighteen years old. She had three other children. She was a slender, frail appearing woman of medium height, very energetic, a skilful nurse, and she proved to be very brave.

I heard Dr. Whitney tell her that it was her skilful nursing that saved the boy. She told me her parents and her husband were Germans. Her name as she pronounced it sounded as though it was spelled "Large." I was in no condition to write. I have always regretted that I did not learn where her home was. She showed me many kindnesses for which I was very grateful.

When my folks at home heard I was wounded my brother-in-law started for Washington to find me. He had a brother who was pay-master in the army, with the rank of major, who happened to be in Washington at the time.

My brother-in-law with the major visited many of the hospitals in and around Washington trying to find me, but without success. Finally the major learned where I was. As there were strict orders at that time to allow no citizen to visit the army at the front, it appeared as though my brother could not get to me, but the major fitted him with a uniform, gave him papers showing he was the major's clerk, which passed him on to the boat that carried him down the Potomac river to Acquia Creek landing, which, was about ten miles from the hospital where I was.

He arrived on May 15th and

stopped with me about one week. When he left

for home he was assured I should be carried to Washington as soon as I

could be safely moved.

He arrived on May 15th and

stopped with me about one week. When he left

for home he was assured I should be carried to Washington as soon as I

could be safely moved.

Photograph of one of the lower front interior rooms of the house taken by John Cummings in 2008. [spotsylvaniacw.blogspot.com] The windows face southwest, or to the front entrance. This may be the room where John Fay was placed.

When the hospital was opened there were about two hundred sick and wounded put into it. Tents were pitched near the house to accommodate most of them. The location was healthy and apparently secure. When men had recovered so they could be safely moved they were carried to Washington, so that by the middle of June there were only about thirty-five remaining in the hospital; about one-third were sick with fever and the remainder were wounded; they, with the nurses, surgeons, and guard, making about eighty men and one woman remaining on duty June 15th. On the night of June 14th the army of the Potomac started on a march northward in the movement which culminated in the battle of Gettysburg.

When the first corps left their camp near our hospital an officer with an ambulance train was sent down to remove us. There was a heavy thunder-storm that night. In the darkness and rain he got lost. When daylight appeared he could see, from the bluffs where he was, the rebel army crossing the river down in front of our hospital about a mile distant.

The officer became frightened. He turned his train of empty ambulances northward and started to catch up with the Union army, leaving us to be captured without making any attempt to remove us. I have never been able to learn who that coward with shoulder-straps was.

When Dr. Whitney learned we had been abandoned he ordered his hostler to mount his best horse (the doctor had two horses) and ride to Washington. The assistant surgeon, a New Jersey man, asked permission to go. Dr. Whitney gave it. He might have escaped himself, but like the brave man he was he stood by us.

*******

Original Narrative, cont'd.

On the night of the 13th of June the army started northward and left thirty four of us patients and the nurses cooks and the Dr in the hospital to be taken prisoners. This we did not like very well but we could not help ourselves. On the 15th the fourteenth SC rebel Regt crossed the river and came up and took us prisoners. They paroled us and went off and we saw no more of them. The next day the 16 th Va. rebel cavalry came over and picketed in vicinity of the hospital, and they had charge of us until we was moved to Richmond. Our army left us ten days rations when they was going. The rebels gave us some flour and bacon. On the 1st[?] of July the rebel docter came over and started us to Richmond it was raining very hard at the time. They took us out of the house that we had used for a hospital, and put us into ox carts and carted us about a mile to the river.

View from treeline on the hill in front of house facing south toward the Rappahannock River in the distance. Photo by Clint Schemmer.

They then put us in an old [flat] boat and ferried us across the river then put into wagons and carried us about four miles, over a very rough road to the rail road. After laying about three hours in the rain at the railroad, they put us into baggage cars that had previously been used to carry cattle in, and started us for Richmond. It was about two o’clock when we started, and we arrived in Richmond a distance of sixty miles at one the next day. The cars was very poor and the road was worse and the cars did not go faster than a man could walk. After we arrived in Richmond we lay in the cars about two hours, much to the delight of about a thousand women and children who came to take a look at a live yankee.

*******

Later version:

The car was very dirty. We were laid on the floor of the car so close together we hardly had room to turn over. The weather was intensely hot. The only opening in the car for light and air was a slide door on each side in the middle of the car. They would not even let us have straw to lie on. Several of our patients were typhoid fever cases and most of them were delirious. Fortunately I was placed near the open door, as was Mrs. Large and her boy. She sat on the floor of that filthy car with her son's head resting on her lap most of the time. About dark the train to which our car was attached started for Richmond. After running a few miles we were side-tracked for several hours. It was a terrible hot night. We were suffering intensely from thirst. The guard would not give us water or let any of the well men of our party who were riding on top of our car get water for us. Once in the night the devoted mother begged so hard of the officer in command of the guard he sent a man to get her some water. She gave me two or three swallows. Oh, how precious it was ! Men in that car were struggling in death agony. One died before we reached Richmond.

We arrived in the suburbs of Richmond early in the morning. About 9 A.M. our car was detached from the train and drawn into the city by horses. We were soon surrounded by a crowd of half grown boys who amused themselves by throwing missiles at us.

Soon a rebel guard was placed around the car and stopped the boys' fun.

I remember the guard was commanded by a lieutenant who was lame from a wound he had previously received in battle. He treated us as kindly as he could. He was the first rebel to show us any kindness since we were captured. He let Dr. Whitney come into our car to help us. He ordered the body of our dead comrade taken out, but it was several hours before we were removed.

It was very hot and we were

suffering intensely. Dr. Whitney

was

standing beside the car in front of the open door when a lady, whose

hair was gray, dressed in a black silk, came down and asked for

permission to speak with the Yankee doctor, which was granted.

It was very hot and we were

suffering intensely. Dr. Whitney

was

standing beside the car in front of the open door when a lady, whose

hair was gray, dressed in a black silk, came down and asked for