The Aftermath of Battle

July 4 - July 5, 1863

Image from the Chrysler Art Museum Digital Collections, www.chrysler.org

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What's On This Page

- July 4th; WHO LICKED ?

- We Swelled the Ranks to Nine

- Condition of the 16th Maine

- Colonel Root's Letter; 94th N.Y. Vols.

- Letters of Chaplain F. D. Ward; 104th NY

- Surgeon John Theodore Heard

- 'The Christian Commission'

Introduction

The following is from Meade at Gettysburg, p. 157. [the text is abridged]. It sets the stage for this page's narrative. At daybreak on the morning of July 4, the reports that came in showed that the enemy had disappeared from the front of the extreme right of the line, but that he still was in force on the left and left center. General Slocum, in command of the right, was immediately directed to advance his corps, and ascertain the position of the enemy. Likewise, General Howard, in the center, was directed to push into Gettysburg to see whether the enemy still occupied the town. At the first sign of the enemy’s withdrawal and before anything definite was known of their intention, the following order was sent to General French at Frederick City in order to gain time in case the enemy were actually withdrawing: The Major General Commanding directs that you proceed immediately, and seize and hold the South Mountain passes with such forces as in your judgment are proper and sufficient to prevent the enemy’s seizing them to cover his retreat. With the balance of your force re-occupy Maryland Heights and operate upon the contingency expressed yesterday in regards to the retreat of the enemy. General Buford will probably pass through South Mountain tomorrow p.m. form this side. At 7 a.m. the following despatch was sent to Major-General Halleck, at Washington. Headquarters Army of the

Potomac, Major-General Halleck: This morning the enemy has withdrawn his pickets from the positions of yesterday. My own pickets are moving out to ascertain the nature and extent of the enemy’s movements. My information is not sufficient for me to decide its character yet – whether a retreat or manoeuvre for other purposes. George G. Meade,

In order to learn the condition and of the troops after the past three days' hard fighting and maneuvering, circulars were sent to all the corps commanders. July 4, 1863. Circular. Corps Commanders will report the present position of the troops under their command in their immediate front – location, etc., amount of supplies on hand and condition. The intention of the Major General Commanding is not to make any present move, but to refit and rest for today. The opportunity must be made use of to get the commands well in hand, and ready for such duties as the General may direct. The lines as held are not to be changed without orders; the skirmishers simply being advanced according to instructions given to find and report the position and lines of the enemy. July 4, 1863. Circular. Corps Commanders will detail burial parties to bury all the enemy’s dead in the vicinity of their lines. Correct accounts of the numbers buried will be kept, and returns made through Corps Headquarters to the Asst. Adj’t Gen’l. The arms, acoutrements, etc., will all be collected and turned over to the Ordnance officers. Reports of the number and kind of each picked up will be reported to these Headquarters. Headquarters Army of the

Potomac, Major-General Halleck,

The position of affairs is not materially changed from my last dispatch, 7 a.m. The enemy apparently has thrown back his left, and placed guns and troops in position in rear of Gettysburg, which we now hold. The enemy has abandoned large numbers of his killed and wounded on the field. I shall require some time to get up supplies, ammunition, &c., rest the army, worn out by long marches and three days' hard fighting. I shall probably be able to give you a return of our captures and losses before night, and return of the enemy's killed and wounded in our hands. George G. Meade,

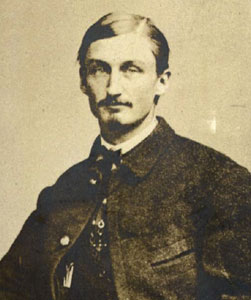

PICTURE CREDITS: All images are from the Library of Congress Digital Collections with the following exceptions. Charles W. Reed's war-time sketches are from the Special Collections of the New York Public Library Digital Collections, [www.nypl.org]; ; his b&w images were accessed digitally from the Book HARDTACK & COFFEE, by John D. Billings; Christ Lutheran Church (known as the College Church at the time of the battle), is from the book 'Gettysburg College Alumni Association, 1882; Timothy Sullivan's photograph of the Baltimore Pike is from the Chrysler Museum of Art Digital Collections, www.chrysler.org; Edwin Forbes sketch of the battlefield & sketch of wounded soldiers in a barn are from Battles & Leaders of the Civil War, Century Publications, 1884 - 1888, Volumes 2 & 3; Color Vignettes from the Gettysburg Cyclorama are from Wikimedia Commons; The illustration accompanying the 16th Maine narrative, is cropped from an image titled, 'Who Would Listen for Footsteps that Nevermore would Come,' artist unknown, as is also, the illustration accompanying Chaplain Ward's letter titled 'Caring For The Dead and Wounded,' from 'Boys of '61' by Charles Carleton Coffin, Boston, Estes & Lauriat; Battle sketch accompanying Col. Root's letter is from From New York Public Library Digital Collections, [www.nypl.org]; Photograph of White Church hospital and the Plaque commemorating the Gettysburg Field Hospitals, Adams County, is from a digital tour of historic Mount Joy found here: [ww.mtjoytwp.us/Tour/]; Surgeons Whitney and Heard are from the authors private collection, photograph by George L. Crosby, 1862; Portraits of A.W. Leonard & Colonel Adrian Root are from the Army Heritage Education Center at Carlisle, PA , Mass MOLLUS Collection; Melvin Walker's image is from "Historic Homes and Institutions and Genealogical and Personal Memoirs of Worcester County, Mass.," vol. IV, by Ellery Bicknell Crane, Lewis Publishing Co., 1907; (found on google books); ALL IMAGES have been edited in PHOTOSHOP. What's On This PageThe end to the fighting at Gettysburg provided a brief period of reflection among the battered regiments of the First Corps. They had been through two weeks of arduous marching and 3 days of brutal combat. Now there was time to tally the cost. On July 2nd, the '13th Mass' numbered 78 men out of 260 that went into the fight of July 1. The other regiments of their brigade were in the same condition. The 104th NY, which fought along side the '13th Mass' on Oak Ridge, numbered only 45 men and 1 line officer. The 16th Maine lost 223 men out of 298 on July 1st, leaving some 75 officers and men left. The 107th PA tallied about 75 - 80 men. Some more men who had been hiding out in the town during the Rebel occupation, joined the ranks on July 4th. The narratives on this page reflect on these sad conditions in the wake of the battle. The page begins with commentary from the '13th Mass', which is relatively quiet regarding losses; -- is it because the hardened soldiers were used to these horrid scenes after a battle? Author Charles E. Davis, Jr. chose to address the subject by quoting liberally from an officer of the Christian Commission, whose report conveys the ravaged landscape. In the 16th Maine, Major Abner Small's writing is most eloquent and movingly portrays the sentiments felt by the shattered troops. Colonel Adrian Root's letter home is more of a straight-forward recounting of the battle on July 1, as the 94th NY experienced it. Upon being captured, Col. Root turned his attention to caring for the wounded men left upon the battle-field after the Federal retreat. Confederate General A.P. Hill allowed Col. Root to gather together a detail of prisoners for that purpose. The salient points of the story are told in his letter home. That letter is followed up by Chaplain Ferdinand D. Ward's careful casualty report for the 104th NY. He compares the number and seriousness of the wounds he witnessed in the hospitals among the soldiers of the 11th Corps, the 3rd Corps and the Confederates left behind by General Lee. The misery and suffering are evident in his controlled words. A short bit on the location of the field hospitals accompanies Chaplain Ward's letters. A short presentation on Surgeon John Theodore Heard, Medical Director of the First Corps follows. This is because Surgeon Heard began his impressive military service as the Assistant Surgeon of the '13th Mass' in 1861. Like Surgeon Whitney, of the regiment, I do not have an extensive record of their accomplishments, but it is satisfying to mention him here. Charles Davis's narrative for the '13th Mass' on July 5th concludes the page. This is primarily the report from the Christian Commission mentioned above. The subject of 'caring for the wounded' continues on the next page with a look at efforts of the soldiers and townspeople, with a few personal letters and reminiscences of '13th Mass' soldiers at the field hospitals. July 4th; WHO LICKED ?From the Regimental History, " "Three Years in the Army" by Charles E. Davis, Jr. Saturday, July 4.

“I believe there was, Jim.” “I wonder if the positions we left, on enlisting, will be open to us as promised, when we get back?” “If we carry on the war much longer as we do now, there’ll be no ‘get back.” “What are you going to do about it?” “Do? Nothing. What can we do?” At this moment a third man approached the fire. “What are you fellows growling about?”

“No, I didn’t. I said, let’s call it a victory.” “You are right, Jim,” said the new-comer. “We’ll call it one, though it draws hard on the imagination.” This conversation reflects pretty well the feeling that prevailed among the soldiers the morning of the fourth. As we reflected on the last three days’ terrible work, we could not escape the impression that it was a repetition of Antietam, for in both cases the enemy was granted “ leave to withdraw” at a time when it could have had little expectation of the exercise of so benignant a privilege. By noon it began to rain in torrents, making the roads so muddy that it was impossible to manoeuver artillery with any advantage, furnishing a good reason to Meade for thanking Providence for granting us a great victory. It was now plain enough to all that the fighting was over, and if Lee would only get back into Virginia we might make the claim, without fear of dispute. At present, however, the enemy showed a strong front, having apparently recovered from the paralyzing shock of yesterday, thanks to our customary irresolutions. We lay all day in a piece of woods to the south of the cemetery, wondering what would be the next move on the checker-board of fate. Desultory firing was kept up by the enemy, whose sharpshooters occasionally hit a man. On one of these occasions, when an officer of our regiment was in the act of raising his dipper filled with coffee, a bullet passed completely through it. “A close shot,” said the officer, and proceeded to drink the remainder of the coffee. Another one of our boys was shot in the thigh;* so the day didn’t pass without some excitement and the customary Fourth of July accident.All images are from the Library of Congress Digital Collections with the following exceptions. *George S. Wise, Company D, as mentioned by Sam Webster. Wise died of his wound on July 12, 1863. Sam Webster kicks things off with a quick wrap up of the day's events in this short diary entry. The 'Jack' Leonard he mentions is probably A. W. Leonard, of Company D, [pictured] who is the only other 'Leonard' in the roster besides the colonel. Acting Orderly Sergeant Joe Kelly died in September of this year, of fever, at Armory Hospital in Washington, D.C. Comrade George S. Wise died on July 12th, of the wound he received from a sharpshooter this day.

Diary of Sam Webster

Saturday, July 4th,

1863 Lieutenant Joe Stuart's encounter with a sharpshooter's bullet was a popular story among the veterans, as it is repeated in the regimental history and the in the following paragraph, which is a very brief excerpt from an article titled, 'Victuals and Drink,' published in Bivouac Magazine, 1884, written by '13th Mass' veteran Clarence Bell. In the trenches at Gettysburg an energetic skirmisher, longing for something more satisfying than tepid water from his canteen decided to concoct a cup of coffee. Wood was very scarce, and there were decided objections against standing up. These little difficulties did not deter him from the effort. So an hour’s diligent search for twigs and splinters secured enough for a fire as large as one’s hand. These were all obtained by crawling on hands and knees over quite a radius. Patient perseverance was at last rewarded, and with a grin almost audible, he sat with his cup of coffee steaming hot resting on his knee, held by one hand while the other was busily engaged in stirring up the sugar. “There’s many a slip,” etc. An insinuating little piece of lead from an enfilading direction, “zipped” through that locality and ripped through that cup close to the lower edge. With one leg almost scalded our hero rolled on the ground, bewailing his lost coffee, and giving vent to some choice expressions suitable to the occasion, but which are left to the imagination of the reader. We Swelled the Ranks to NineThe following two excerpts are from Sergeants Melvin Walker and Austin C. Stearns memoirs, both of Company K. Walker's remembrance is part of an article titled, "A Personal Experience" published in Thirteenth Regiment Association Circular #24, December, 1911. Some of the story overlaps what has already been posted on the July 1st page of this site, but is included for context here. Stearns memoirs are from the book, "Three Years With Company K," Edited by Arthur Kent, Fairleigh Dickenson Press, 1976. Melvin Walker; 'A Personal Experience' [concluded] This story is set in the Church Hospital on Chambersburg Street in Gettysburg. The narrative begins on July 1st. All images are from the Library of Congress Digital Collections with the following exceptions.

I was taken to a large church on Carlisle street, where our division hospital had been established on the ground floor. The large vestry was fast filling and before night was packed with men covering the floor. An operating table was placed in an anteroom opening off the main hall and here our surgeons worked with knife and saw, without rest or sleep, almost without food, for thirty-six hours before the first round had been made. About five o'clock the town was occupied by the enemy, the sentry was shot down. A chaplain of a Pennsylvania regiment was killed on the steps leading to the room above, and one of our own surgeons was wounded. A Confederate guard was placed over the hospital, but otherwise we were left to ourselves. After the surgeons' work was done we had no care save such as the few less seriously wounded comrades could give. The weather was very hot; we were wholly without food; the floor was drenched with blood and water and men were dying on every side. The First night twenty-three dead were carried from our room and laid beside the church awaiting burial. While the suffering from inflamed wounds and burning fever was intense there was no loud outcry, only sighs and groans and calls for water. Here for three nights and days we watched and waited, listening with almost breathless interest to the tumult of the fighting of the second and third days. We heard the crash of guns, the long roll of musketry, the cheers and yells of the opposing lines as they swayed back and forth through the changing fortunes of the day. Frequently Confederate stragglers dropped in to jibe and boast of certain victory on the morrow and the speedy success of the southern cause. Finally, when Picketts' famous charge ended in dire disaster, we heard the resounding cheers of our gallant comrades and we joined the swelling chorus; with all our hearts. General Ewell had his headquarters across the street and from the going and coming of aids and orderlies far into the night we were sure the enemy's lines were being withdrawn and that after suffering overwhelming losses in the three days' fighting Lee was about to retreat.

Early next morning hearing scattering shots nearby I got into the seat of a window opening on the street. Soon a squad of the enemy's skirmishers ran past the church stopping to fire and then hurrying on. A moment later I saw a few of our boys in hot pursuit firing as they ran, and close behind a regiment in column of fours bearing aloft the flag we loved. Turning to my wounded comrades I shouted, "Boys, here they come, here is the old flag." Hunger and distress and even the agonies of death were forgotten and with tears of joy and shouts of rejoicing we cheered the dear old flag, emblem of all we held most dear, some indeed with dying breath. So was ushered in that glorious morning anniversary of our nation's birth and assurance of a purified and reunited people to be indeed a beacon light of liberty to the downtrodden and oppressed of every land. After a few days I was, with hundreds of others, transferred to York, Pa., where a large hospital had been opened. After some eleven weeks spent here and at another hospital in Baltimore, my wound healed and I was permitted to return to my regiment, then in Virginia. I found the old regiment in camp near Rappahannock Station. The numbers had been greatly reduced by losses at Gettysburg and elsewhere. More of Sergeant Walker's hospital experiences at York, PA are posted on the next page. Austin Stearns' narrative picks up on the morning of July 4th. I was awakened early in the morning by the rain coming down in a smart shower, and starting up, went for the street. A union soldier who was a prisoner like myself warned me not to venture too far as the bullets were singing merrily around. We waited a few moments and then, peeking out from behind the building, saw a union soldier with a gun in his hand up by the Diamond, then another and another until there was a large squad marched into sight. We motioned them not to fire, but to come to us. They, seeing we were union men, came slowly down, as the rebs were down that street slowly falling back. Those that had been prisoners now came out from the houses and backyards, glad to think and know that we were free again. Some of the boys knew where there was some rebs sleeping and they were made prisoners. Amongst the number was the drunken Quartermaster, who had been sleeping off his bad whiskey, and a more sheepish looking man I never saw then he was. The boys recognizing him began taunting him by asking him “how many Yanks he could lick this morning?” and, if he felt like taking a turn with any, they would see he had fair play. But the fight was all out of him; he had no desire, was as humble as anyone could wish. It was soon noised around that Lee had given two hours for the citizens and the wounded to leave the town in, and then he was going to shell it. I did not credit the report, and still did not know but it might be true, so finding Fay and going in and bidding the boys good by (for they were not going to be moved), we shouldered our knapsacks and joined the long line of citizens and wounded soldiers over the pike road that leads to Baltimore.

Pictured is the Baltimore Pike leading south out of Gettysburg, taken by Timothy O'Sullivan from the roof of Evergreen Cemetery Gatehouse, July 7, 1863. Oak Ridge is seen in the distance behind the town. Image from Chrysler Art Museum, digital collections. One idea of our leaving the town was to see if we could get anything to eat, for we were getting decidedly hungry. In going up a street that led out of the town, we saw an open door, the first we had seen, so we entered in and found an elderly couple seated at a table eating. We asked them if they could spare some for us, offering to pay for all. The man pointed to a few slices of bread, said that was all they had, but we were welcome to a slice; the lady buttered a slice apiece and we ate it, while the man gave some of his experiences of the last three days. Resuming our walk, we continued along until we came to a large barn – about two miles, I should think, from the village. Here was one of the hospitals, and here were hundreds of wounded men of both armies. We tried to get something to eat but there was nothing. Fay said he would go to another farm house that was just over the fields and try his luck if I would furnish the money. I gave him a dollar and told him to get something if it was only salt pork. Fay soon returned without any thing, everything was all ate up. Fay was a hearty eater and needed food more than I did. We again made application at the barn and was told that when some beef that was then boiling was done we could have some. There was nothing to do only wait, so we sat down and patiently waited, if it is possible for a very hungry man to do so. Another glimpse of Dr. Heard comes from Colonel Charles Wainwright's war journals.

At last it was announced as done, and those that were waiting were requested to fall into line and receive their rations. We that had dishes fell into line and marched up past the big pot and received about a pint of liquid that a very poor piece of beef had been boiled in. Fay had no cup so as soon as we could we drank the water and Fay fell in and went round, but by the time he reached the pot it was nearly empty and he only received half as much as those first served. It was now well along into the afternoon, and we went and sat down and talked the matter over of what it was best for us to do. We concluded it was best for us to stay and rest where we were and in the morning find the regiment, so we prepared a place behind a fence where we thought we would not be disturbed and at dark lay down. It had rained in showers all day and there were little pools of water all around. I noticed one just behind the fence when we lay down. I was awakened in the night by a stream of water running through where we lay and, rousing up, found it raining hard and we half covered up by water. I said to Fay “are you in for it?” He said “Yes,” and we both lay still and let the water go where it would. The cause of our trouble was that some one in the night had hitched a horse to the tree on the other side of the fence and his stamping had loosened the bottom rail which had served as a dam, and let the water down on us. In the morning we folded our rubber blankets and

looked

around for rations. The prospects at the barn were not

encouraging, so we were turning our attention in another direction when

we saw a long string of teams coming up the road and, turning into the

field near the barn, we with others went to see who they were and what

they wanted. We found they were from York, Pa. and were

loaded

with food and other goodies contributed by the citizens of that

place. After hearing of the victory, they had in a few hours

collected enough to load down twenty teams and they had been all night

on the way. The food was all consigned to the Surgeon in

charge

of the Hospital, so there was no prospect of our getting any.

I

saw one of the drivers eating a big doughnut and, thinking he might

have more, asked him if he had any of them to sell. He said

he

had none, only took those few for a lunch and that was the

last.

The contents of his wagon he knew nothing about for he only drove the

team. At length I saw Dick Wells of the “Commissary”; he saw me at the same time and we had many questions to ask and answer. On [our] arriving at the wagons, he told us to help ourselves, and we soon filled our haversacks with coffee, sugar, pork, and hardtack, the standard articles of a soldiers diet. He told us the regiment was where we fought the first day, and bidding him a good morning, we moved on until we came to a stream of water, where we stopped to cook breakfast. Other soldiers were doing the same, and as fires were already kindled, we soon had a strong cup of coffee with hardtack fried in pork fat. Being very much refreshed and anxious we put forth extra exertions, for we wanted to be with the boys. We went over the “Hill,” stopping for a few moments to see the effects of the shelling in the cemetery, then down town to the Diamond. We were going right on out to the scene of our first days fighting when we were stopped by a union soldier who wanted to know where we were going. We told him, and he said he guessed it was not in that direction, for he was one of the pickets. We returned into the town and went to the hospital, found the boys as well as could be expected, stayed only a few moments and started to find what it now looked might be a long chase. On coming out I saw Col Coulter of the 11th P.V. and enquired of him. He told me where it was a short time ago, but said the troops were getting ready to move. We went in the direction he told us, and in going out saw a young lady selling onions [and] bought five for six cents. We went over the fields where the terrible fighting of the 3d had taken place, and on every hand was thickly strewed the effects of the fight. We darst not stop long, although there were many things that attracted our attention and we would like to see. I picked up a sword (and carried it some ways) that I would like to have kept, but threw it away and selected a gun instead.

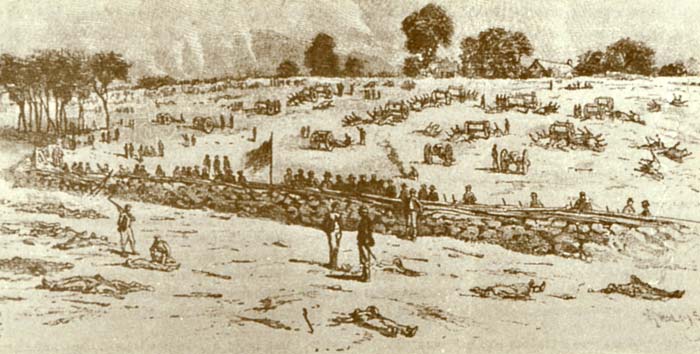

War Correspondent Edwin Forbes sketched Cemetery Ridge near the Copse of Trees after Pickett's Charge. Note the dead bodies and the dead horses. Way down towards “Round Top” we at

last

found the brigade, or what was left of it. The 13th had 80

men,

which was a fair average number. K was commanded by Lt.

Warner

and had seven men; we swelled it to nine. It is needless to

say

that the boys were glad to see us and hear from others of some we knew

nothing of. Major Gould was in command, Col Leonard was

wounded, Gen’l

Paul lost both eyes. Robinson, our division Gen’l, was

wounded,

and I don’t know how many more were in the hands of the

enemy.

We had after a tremendous hard-fought fight gained a victory, and there

was no doubt of it. The boys were all feeling good over the

result, and if the victory were followed up and the fruits reaped,

there would be a prospect of peace soon. This made the boys

anxious, yes, more than anxious to be on the heels of the fleeing

rebels, for it was now known that Lee was in full retreat towards the

Potomac. Condition of the 16th MaineThe '13th Mass', as reported by Lt.-Col. N. Walter Bachelder, numbered 15 officers and 79 enlisted men, on July 4th after the hard fought battles. The other regiments of 'Paul's' Brigade, faired about the same. The following excerpts of source material from the 16th Maine, 94th New York, and the 104th New York give a good account of this. The following passages are from, 'The Sixteenth Maine Regiment in the War of the Rebellion; 1861-1865' by Major A.R. Small, B. Thurston & Company, Portland, Maine, 1886. July 4. The remnant of the Sixteenth is sadly depressed. The loved colonel on his way to Richmond – to the prison-pens of the South; the brave lieutenant-colonel at the point of death; our valued surgeon, Alexander, wounded and a prisoner; all the line officers but four either killed, wounded, or missing, and a fearful list of casualties among the men. We thought of the brave fellows started on a pilgrimage worse than death. There is said to be an average time in every man’s life, when he learns to cry. I believe many of us graduated in this accomplishment that night. Among those captured was Benny Worth, of Company E. He was kept busy in the unwelcome task of carrying United States muskets from the field, July 2d. He quickly discerned that the rebels were being worsted, and shrewdly worked his way into the hospital. Procuring some bloody bandages, he bound up an imaginary wound in his ankle, and hence was left behind, while the well and unharmed were marched toward Richmond. Worth rejoined the regiment on the morning of the fourth.

Among the incidents of the battle, is one written by Adjutant Small for the Richmond Enquirer, brought out by the following letter published in the Petersburgh Appeal: - Mr. Editor: - Please send me the paper for another year. I don’t now how I could do without seeing a paper every day. It may be an old woman’s fancy, but somehow I am not yet hopeless that I shall yet hear something to cheer my last days. My bright, manly boy, William left in ’61 to join the Confederate Army. He was then seventeen – my only boy – and from then till the battle of Gettysburgh, I saw him twice, and heard from him often. In that dreadful battle he was left wounded on the battle-field. His fate I know not, but I read the papers every day, hoping that I may gain some tidings of him. I hope on, and still hope that he may be alive. The shadows are growing longer, and a dark river is rolling nearer and nearer to me; but beyond the light grows brighter and brighter. William may be there. I am waiting for my Master’s call. I have just been reading the sad story of bereavement, and it brings vividly before me the battle of Gettysburgh and its attendant incidents. This sadly patient mother tells her story and brings to mind, distinctly, a spot in the grove at the left of Cemetery Hill, nearly in front of General Meade’s head-quarters, where were lying a number of wounded, in grey suits, fallen in the last brave charge on the 3d of July. Sadly I made my way among the dead and dying, proffering such assistance as sympathy dictated. One poor fellow, about twenty-five years of age, was shot through the body. His wants were few – “Only a drink of water. I am so cold – so cold!” Won’t you cover me up?” And then his mind wandered, murmuring something about “Dear mother. So glad ‘t is all over.” Then a clear sense of his condition, and would I write to his father and tell him how he died; how he loved them at home? “Tell them all about it, won’t you? Father’s name is Robert Jenkins. I belong to the Seventh North Carolina troops – came from Chatham County. My name is Will -, ” and tearfully I covered his face. Perhaps he was this mother’s boy; perhaps not, but he was some mother’s darling.

A little further on my attention was attracted toward a young man, of Kemper’s brigade, I think. Kneeling down by his side, I looked at his strikingly handsome face some few moments, when he unclosed his eyes and looked steadily into mine with such a questioning, hungry look, an appeal so beseeching, so eloquent, and I had not the power to answer – could only ask where he was wounded. “Don’t talk to me, please,” he said. A moment after he touched his breast, and I saw there was but a chance for him. Asking if he was afraid to die, he replied, “No; I am glad I am through. Oh! I hope this will end the war; will it?” I asked him if he was a Christian, and I think he told me he was not a professor, “but tried to be good,” when a spasm of pain closed his eyes. I could not bear to leave him, and, putting my face close down to his, he suddenly opened his eyes. I shall never forget their unearthly beauty, and the sweet, trusting expression which overspread his whole face, as he said to me, with a motion as though he would throw his arms around my neck, “I am going home – good by!” I did weep; I couldn’t help it. I do not recollect his name; he might not have told me. I only remember that boys from the Sixteenth Maine carried him to the field hospital because they wanted to, although they, too, saw it was nearly over. Colonel Root's Letter; 94th N.Y. Vols.The newspaper article presented here was found among the collected digitized pdf files for the 94th N.Y. Vols. at the website for the New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center. Immediately after the battle on July 5th, Chaplain P. G. Cook of this unit, estimated the regiment's loss at 7 killed, 60 wounded and 160 missing. Major Moffet claimed they could only muster 80 men of the estimated 350 who entered the fight.* Chaplain Cook wrote that one hundred twenty men were present for duty July 5. Buffalo Commercial Advertiser Letter From

Colonel Root. Editors Commercial Advertiser:

I must not neglect to avail myself of the opportunity of writing to you, which my present respite from active duty affords me, and remembering the interest you have always taken in my regiment, will endeavor to give you a connected account of its recent experiences. I last wrote you from Aquia, of which post and its defenses I had been placed in command. When the Army of the Potomac moved in pursuit of General Lee, General Hooker sent me three additional regiments of infantry, with orders to hold the post, and cover the embarkation of the sick of the Army and the immense quantity of supplies in depot at Aquia. On the 17th of June

the

embarkation had been completed, without loss, and I received

telegraphic orders to evacuate the post and proceed to the mouth of the

Monocacy River, in Maryland. Taking transports to

Washington, I

marched thence overland, reaching the Monocacy on the 20th ult.,

guarded the Potomac from the Monocacy down to Edward’s Ferry until the

26th ult., when Major-General Reynolds arrived and crossed the Potomac

with his First Army Corps, and obtained permission for me and my

regiment to accompany him. I reported to General Paul, commanding First

Brigade, Second Division, at Middletown, on the 27th ult.; 28th,

marched to Frederick; 29th, to Emmetsburg; 30th, marched nearly to

Gettysburg, our Brigade arriving at about one o’clock P.M., and finding

Wasdsworth’s Division engaged with a superior force of the enemy, and

suffering severely, General Reynolds the Corps Commander having been

killed early in the action. Our Division passed on to the

left of

Gettysburg, and advanced to Wadsworth’s support, the First Brigade

forming line of battle upon a wooded ridge, and, by direction of

General Paul, throwing up hastily constructed breast-works of fence

rails, &c. These were scarcely completed before we

were

ordered to move to the right, and having moved about five hundred

yards, found ourselves under a heavy fire of musketry and

artillery. Meantime the enemy pressing the corps in superior force, succeeded in flanking it on both sides, and forced it to retreat in haste through Gettysburg, to a hill beyond. In passing through Gettysburg, the enemy headed off a portion the corps, and captured a large number of prisoners, among whom were nearly two hundred of my own regiment. While all this was transpiring, I remained helpless and semi-conscious on the field, and was taken possession of by some exultant rebels. By a sort of retributive justice, my captors belonged to the 33d North Carolina regiment, the identical regiment captured by my brigade at the first battle of Fredericksburg, December 17th, 1862.** When the rebels had occupied Gettysburg their pursuit ceased, and having some leisure they turned their attention to their prisoners, of whom they had taken about four thousand. The 33d North Carolina recognized me, shook hands vigorously, and escorted me to their Colonel, who anxiously inquired if “I’d take a drink,” at the same time proffering a canteen of whiskey. Later in the evening my generous captors took me to the headquarters of Gen. A.P. Hill, who gave me a good supper, and offered to parole me at once, or to wait and exchange me after the Confederates had taken Baltimore. I preferred being exchanged at Baltimore, but subsequently I thought of the hundreds of our wounded men in the rebel lines and asked permission to attend to their wants, and offering to be personally responsible for a detail of prisoners, if they could be given me. Gen. Hill at once gave me permission to attend to our wounded, and subsequently gave me a detail of one hundred and fifty men of the 94th N.Y.V. to assist me. I was required to sign an obligation to remain prisoner of war until duly exchanged. All the other prisoners were paroled and sent to Carlisle, but I declined the parole, as did my men also, and only accepted the provisional parole, in order to be enabled to relieve the sufferings of the wounded. That night I passed on the battle field, doing what little I could to relieve the misery around me. All I could do was to supply water and receive dying messages for home friends, and encourage the less severely wounded. I shall never forget that first night, no, nor any of those days and nights, until the long and fearful fight had ended. - But that first night was the most painful of all, for with the exception of one man, I was alone in endeavoring to assist the hundreds of wounded men around me, and meanwhile suffering inexpressible distress myself, from very consciousness of my inability to materially relieve the misery which wrung with useless sympathy every chord of my nature. But the next day, July 2d, my detail of 150 men of the 94th, came to my assistance, and while the fight raged furiously at the front, my brave fellows labored assiduously under a constant fire of our own batteries to collect our wounded men.

The poor fellows were placed in a barn, until one hundred and seventeen had been placed here, and there was no more room, and then the rest were laid in rows on the ground outside. We had no luncheons, but we had water, and the men worked faithfully in their labor of mercy, rendering me prouder of them than I had ever been before. That their labors were not entirely devoid of risk, may be inferred from the fact that several shot and shells passed into and through our improvised barn hospital. One of these shells exploded and tore the lower jaw from a Tennessee Major who had stopped to look at our wounded, and he died in a few moments. Of the great artillery fight of July 3d, and subsequently of the magnificent infantry charges of rebels, I was as you may suppose a most interested spectator, but I cannot now take the time to describe them. I will only say that after having been present at a number of important engagements, the battle of Gettysburg, in my opinion, exceeded all previous battles of the war in sublimity and grandeur, as well as in carnage and subsequent human misery. You will bear in mind that within the rebel lines, I was at perfect liberty to go where I chose. I was a witness to their losses as well as our own. There were numerous instances in which it seemed as though all possible human misery had been concentrated. Can you imagine anything more appalling than human beings with shattered jaws, limbs, heads, helpless, speechless, yet conscious, and with the pleading eye eloquent with imploring agony. I saw many such and could only leave them to perish slowly where they had fallen. But I will not shock you with a detailed description these horrors. During the night of the 4th inst., the rebels began their retreat, disappointed, but very far from being dispirited; their artillery intact, their cavalry splendidly mounted, their infantry in perfect discipline. The officers bade me good bye, saying as they shook hands, that they hoped to meet me again under pleasanter auspices. I should like very much to tell you of some of the strange incidents which occurred to me, during my involuntary sojourn with the rebels, but cannot do so now without violating the terms of my parole. You will doubtless be surprised to learn that I met several Buffalonians in the rebel army, (where won't you meet them?) On one occasion while walking over the field I met a mounted rebel officer, who after passing me, turned his horse, and overtaking me, asked if I was not Col. R. On my replying in the affirmative, he asked me if I knew him. I looked at him a moment, and replied, “Yes, you rascal, I know you very well, I used to see you licked every day at Fay’s School.” Whereat the rebel laughed, and announced himself as the Quarter Master of the 8th Georgia regiment and wanted to know if he could do anything for me. On my replying that I wanted nothing but Surgeons, which he could not supply, he began a review of the old school-boy days of the long past childhood, asking after many who had been long ago dead and buried, and finally, and with hesitation, inquiring about his father and mother. I remembered that his brother was lost at sea, and I expressed the opinion that poor “Gussy” had been the more fortunate of the brothers.- Whereupon the Confederate smiled gravely, and said that he must be going along, as he had been detailed to “borrow” some horses from the Pennsylvania farmers. Then with a request that I would send his love to his parents and family, my old schoolmate, Sammy Hall, rode away to negotiate his “loan”of some horses from the Pennsylvania farmers. This letter is becoming too long for you to read with comfort, and I will finish it forthwith. My own physical condition is quite satisfactory, with the exception of an occasional twinge of pain in my cranium, consequent upon what the surgeon declares to have been a “concussion of the brain.” I regard his opinion with much satisfaction, in view of the fact that a friend of mine has frequently told me that I had no brains, or I would be at home behaving myself, instead of wasting my days as a three years’ volunteer. I am now awaiting instructions as the validity of my parole, which I consider valid and binding, and shall fulfill its conditions, to the extent of my ability, my only object in assuming them having been to relieve the sufferings of our wounded men. I cannot state definitely the losses in my regiment during the recent battles. About one hundred men only are now with the colors, but doubtless most of the “missing” were taken prisoners. I do not yet know the number of killed and wounded. I remain yours very truly, *Another officer, Walter T. Chester claims the regiment's strength was 420 when it entered the fight with only 78 present directly following it. The consensus is the regiment had about 410 men when it went into action. [See here]. Letters of Chaplain F. D. Ward; 104th NYThe newspaper articles presented here were found among the collected digitized files for the 104th N.Y. Vols., at the website of the "New York State Military Museum and Veterans Research Center." Colonel Gilbert Prey's Regiment, 104th N.Y. Vols., fought along side the '13th Mass,' fronting north on Oak Ridge, July 1st. The other regiments of General Paul's Brigade initially fronted west. The experiences of the 104th N.Y. will be the most like those of the '13th Mass.' The morning of July 2nd, the 104th N.Y. could only muster about 45 officers and men. It is estimated they brought about 250 into the battle. Chaplain Ferdinand D. Ward, 104th N.Y., arrived at the Gettysburg battle-field on Monday, July 8th. After touring the hospitals he wrote the following interesting letter home. A Visit to the Pennsylvania Battle-Field Casualties among Our Volunteers. First

Army Corps, Hospital. – Camp near Editor Herald – I arrived in Washington a week ago this morning, after three days uncertain journeying via Harrisburg, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and by two days more busy trying, secured a War Department Pass to reach the Army of the Potomac; but my object being not so much to reach the Army as the wounded, I found it necessary to get another pass from Gen. Schenck, at Baltimore. This took another day, and I got here Monday evening. I find our 104th Regiment like all in this corps, terribly cut up, having done the principal part of Wednesday’s fighting, and been in all the later fighting on the left, which was very severe on Thursday evening, and most of the day on Friday. I have visited the 11th and 3d corps Hospitals, but do not find them so badly destroyed as the 1st, although their losses are terrible indeed. Especially the 3d, where the wounds so far as I have visited, are more severe than those of the 11th. I think in them all, the killed in proportion to the wounded is smaller than usual. We have many of the rebel wounded among us, who are much more horribly mangled than ours. I judge this may be partly from their removing many of theirs, leaving only the worst cases, and partly from the greater supply, and more effectiveness of our ammunition. If we only have their “worst cases,” and they are at all in proportion to ours, the number here tell an awful tale of their whole loss. I have stolen as much time as I could feel like doing, from the duties that press upon every working man on all sides, to visit the field. These scenes have been so often described, I will not attempt any details of its horrors. It is enough for me to tell you that here is a line of battle extending eight miles, nearly every foot of the whole distance marked by all the usual indications of a fight desperate and sanguinary as any on record. [transcribed by Brad Forbush] This letter continues with a list of wounded which I have omitted. A week later, on July 15th, Chaplain Ward wrote home again with a more accurate list of wounded. That letter is written from White Church Hospital, which is found in Mount Joy Township, Adams County, Pa. I found the following information about this Field Hospital on-line. Mark’s German Reformed Church “White Church” (Evangelical Holiness Church) “White Church” (founded in 1789) was already an active church before the Battle of Gettysburg. In 1863, the building was described as a wood church constructed of hewed logs, weather-board on the outside and plastered on the inside. Locally it was called “White Church”. The Church became a hospital immediately following the Battle of Gettysburg. By July 1, 1863, it was found the doors were taken off the church and one door was being used as an amputation table. The pews were taken out and some were cut up to make bunks. Tables were used as beds for the soldiers. There were 1229 wounded soldiers treated at the 1st Corps hospitals. The hospital was under the supervision of General Patrick, Provost Marshall of the Army of the Potomac. He recalled “I took possession the evening of the 1st, of a small white church building on the Baltimore road …Besides the men of our army, the next day 2nd July Gen. Patrick had placed on the lawn and grove near the church several hundred wounded rebels, who were fed and had their wounds cared for…” LIVINGSTON REPUBLICAN (Geneseo, New York) Our

Army

Correspondence. “White Church Field

Hospital Of 2d Div., Mr.Editor

: - I have delayed communicating to you the results of the late battle

in order to greater correctness of statement. Waiving all

account

of the engagement itself, I would notice briefly the position of

officers and privates of the 104th. Col. Prey, Major Strang,

Dr.

Rugg, and Lieut. McConnely are the only officers with the Regiment,

which contains but 40 privates. Quartermaster Colt is with

his

train. Lieut. Col. Tuthill has a serious, though we hope not

dangerous wound. Color Sergeants Buckingham and Shea were badly wounded – the former losing a leg also Sergeants Lefferts, [Joseph Leffleth] mortally in face – having lost a leg – Wylie, Gearhart, Harris, Shea, Pierce, Foster, Culver, Cutler, Carr, Curtis, and lt. Germain, with Corporals Powers, Stanton, Sudbury, Cunningham, Tipkie [Henry Zipkie], and Baker, in the Hospitals at Gettysburg; and here I have seen Privates A. Lewis, P. Goller, A. Saubier, D. Richards, Austin J. Roberts, E. G. Washburne, [E. C. Washburne, G] J. P. Wells, F. Shea, A. H. Peabody, J. Nubfang, [J. Newfang] G. Chick, M. McGee, W. Hind, P. Garry, M. Flynn, E. Faucher, E. Whipple, S. Streeter, J.B. W. Jock, W. Wetham, J. Weedright, W. Singleton, G. Laudwick, [also Lodowick] H.W. Hurlburt,[?] A, True, P. Cannon, A. Hughes, J. Sweeney, J. W. Parr, N. Wallace, P. Clark, M. Maxson, N. Peaswick and A. Pratt, with many missing, most of them will, by God’s blessing, recover, though not all. In collecting the names of deceased soldiers, I have aimed at great correctness, knowing the painfulness of a false name. I have just returned from the Hospital. While there I asked the inmates to give me the names of those who to their certain knowledge, died on the field, or subsequently, as the result of wounds. They gave me these, (many more, alas to be added)**

This catalogue will be painfully enlarged as time passes on. It will be observed that the loss of officers is specially great. In due time there will be a thorough re-organization if not consolidation of the Regiment.

CHAPLAIN.

**I have cross-referenced the names on Chaplain Ward's list of soldiers killed, with other newspaper sources and tried to correct some of the errors. The corrected names appear in brackets. Surgeon John Theodore HeardThe above letter written by Chaplain Ward is addressed from the White Church Hospital. A picture of the church accompanies the letter. The field hospitals established in town on July 1 were over-run by Confederate forces. When the rest of the Federal army arrived at Gettysburg, new field hospitals were established in what is today called Mount Joy Township near Gettysburg. The plaque pictured commemorates these hospitals and also mentions Surgeon J.T. Heard, Medical Director of the 1st Corps, Surgeon John T. Heard began his volunteer service with the '13th Mass Vols. The plaque reads: ARMY

OF THE POTOMAC The division Field Hospitals of the First Corps were located July 1st at the Lutheran Theological Seminary, The Penna. College, The Courthouse, The Lutheran College Church, and other churches and Buildings in Gettysburg. When these fell into the hands of the Confederates the Chief Medical Officers Remained with the Wounded. July 2nd Hospitals were established near White Church on the Baltimore Pike. These Hospitals cared for 2379 wounded. Medical Director 1st Corps Surgeon J.T. Heard, U.S. Volunteers; 1st Division Surgeon C.W. New, 7th Indiana Infantry; 2nd Division Surgeon C.J. Nordquist, 83rd N.Y. Infantry; 3rd Division Surgeon W.T. Humphrey, 149th Penna. Infantry. Medical Officer in charge of the Corps Hospitals, Surgeon A.J. Ward, 2nd Wisconsin Infantry. [click on the image to view larger]. Dr. Heard is also referenced.in one of Chaplain P.G. Cook's letters home, (94th N.Y.) explaining how Colonel Root was able to organize a detail of prisoners to help care for the wounded following the first days battle. The terms of the acquired parole were printed in the newspaper: Gettysburg, Pa., July 3, 1863. Surgeon Hurd, Medical Director of the First Army

Corps, United States

Army, having applied for a detail of Federal prisoners for Hospital

purposes, and for attending to the wounded and burying the dead, the

following named prisoners of war, belonging to the Ninety-Fourth

Regiment, N.Y. Volunteers, having declined to avail themselves of the

ordinary parole, are hereby detailed for the above duties, the

condition being that they will not attempt to escape nor take up arms

against the Confederate States, nor give any information that may be

prejudicial to the interests of the Confederate States until regularly

exchanged and should the United States Government effuse to consider

this parole as valid and binding, and refuse to exchange the following

named prisoners, then they (the following named prisoners, are to

remain prisoners of war to the Confederate States Government until

regularly exchanged after returning within Confederate lines, and the

detail of prisoners are to be subsisted by the Confederate States

Government so long as they remain within its lines.

Col. Adrian Root, 94th N.Y.V. (wounded) is permitted to take charge of

the detail upon the above conditions. (A list of the soldiers named for the detail from the captured men of the 94th N.Y. follows). -From pdf newspaper file at the New York Military Museum; July 14 letter of Chaplain Cook; Commercial Advertiser, July 18, 1863.

Although they spelled his name incorrectly as 'Hurd', this is the same Dr. Heard who began his distinguished army career in the medical service, as Assistant Surgeon of the 13th Massachusetts. A glimpse at Dr. Heard's service with the '13th Mass' early in the war, is gleaned from one of Private John B. Noyes letters home, dated November 22, 1861. Private Noyes wrote: “I don't know what reports you have heard of the Surgeon. I have seen nothing in him to unfit him for his duties. He is not very popular in the Regiment, partly owing to his infirmities, that is his fatness, and partly to the fact that Dr. Heard, the Ass't. Surgeon is the favorite. Hurd is a slim built man, very dark in complexion, quick, active, and more neat in attire than his superior officer. Of two Doctors, one must in time fall under when their patients are the same. The chief complaint against Dr. Whitney, however is his giving too much quinine to those affected with the chills. Several men in our Company haven't ceased to shake since we left Antietam & will not feed on quinine. Now Dr. Hurd prescribed for those cases, although his sickness prevented his constant attendance. Dr. Whitney agreed with Hurd on the quinine subject; that is on its use, and the benefits to be derived from it by those affected with chills & typhoid fever. So you see Dr. Whitney suffers where Hurd should bear the burden...” Pictured are Assistant Surgeon J.T. Heard and Surgeon Allston W. Whitney, 13th Mass., at Williamsport, MD in February, 1862. The image is by George L. Crosby, and cropped from a larger image in my personal collection of photos - B.F. The following two paragraphs of research on Heard's family was compiled by Dr. John Hatenhauer of Wausau, WI, December, 2015. Dr. Hatenhauer's is the custodian of some of Surgeon Heard's personal artifacts. His research extends beyond these excerpts. Any interested readers may contact me for more information. - B.F., Jan. 2017. John Theodore Heard was born on Hancock Street in Boston on May 28, 1836. His great grandfather, Nathaniel Heard, was one of the Minute Men who marched from Ipswich to Lexington when the call to arms was sounded on April 19, 1775. His father, John Trull Heard, was born on May 4, 1809, also in Boston. On October 17, 1832 he married Almira Patterson of Boston. The ceremony was performed by Ralph Waldo Emerson. There were three children from the marriage. Two, a boy and a girl, died in infancy. John Theodore survived. He was called “Theodore” by his parents. In 1880, following the death of his father, John Theodore wrote a memorial for him which was published in the New England Historical and Genealogical Register in 1882. This memorial describes his father as pursuing a “mercantile life”. Although not mentioned in the memorial, his father was a distiller (Trull and Heard Distillers) who was financially very successful. In 1859 the family was living at 4 Louisburg Square, perhaps the best neighborhood in Boston then and which remains so today. Subsequently the family was consistently listed as living at 20 Louisburg Square. As will be seen later it seems possible that both properties remained in the Heard family until nearly the mid 20th century. John Theodore Heard attended Boston Latin and other private schools for his early education. He then attended Harvard Medical School from which he graduated in 1859. The Francis Countway Library of Medicine of the Harvard Medical School has two of Dr. Heard’s diaries as well as bound volumes of his Case Records as House Surgeon at the Massachusetts General Hospital from May 1858 to May 1859. The first diary was kept on a Trip to Cuba, February and March 1856. The second was kept on two trips to Europe between 1859-1860. On the first trip to Europe Heard sailed on the “Asia” from New York to Liverpool departing on November 23, 1859. His diary records visits to hospitals, infirmaries, clinics, medical society meetings and physicians’ offices in London, Dublin, and other cities in Ireland and Scotland. Heard records that he “…fell in with a Scotch MD by the name of Hunter who had been in the English Army in the Crimea”. Perhaps this is what prompted Heard to purchase Notes on the Surgery of the War In The Crimea by George H.B.Macleod M.D. ( originally published in 1858, Heard’s personal copy is in my collection. On the third page, in his hand, is his signature and the date July 16, 1861 which is the date he mustered into the 13th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers.) While in Europe he also “…witnessed an amputation at the hip which took 45 seconds from the time he (the surgeon) was handed the scalpel”. Heard returned to the United States on May 29, 1860, arriving on the “Arabia”. It was not uncommon in that era for young physicians who could afford it to polish and enhance their medical training by visiting European clinics. European medical education was superior to that in the United States at that time. Less than two months after returning home Heard left for Europe again, this time sailing from Boston on July 12, 1860 on the “Adriatic”. He arrived in Southhampton and spent much of his time in London and Paris. However he was in Moscow when news of the firing on Fort Sumter reached him. According to a Latin School classmate who encountered Heard at the Cunard office in Paris, Heard had travelled “night and day” to reach Paris and when he found that all the cabins on the ships to the U.S. had been booked offered to sail in steerage. That wasn’t necessary as his classmate took him into his cabin for the trip. Heard returned to Boston where he mustered into the 13th Massachusetts Infantry as Assistant Surgeon on July 16, 1861. The Surgeon of the 13th Regiment was Allston Waldo Whitney. On May 1st, 1862, J. T. Heard was appointed Surgeon, to the 1st Brigade of the 2nd Division of the First Army Corps, which was at the time Duryea's brigade of McDowell's Corps. On October 28, 1862 he was appointed Chief Surgeon of the same division. Just two weeks later he was appointed Medical Director of the First Army Corps, under Major-General John Reynolds. Clearly Surgeon Heard was efficient, and well connected. While serving on the First Army Corps staff, Dr. Heard befriended Colonel Charles Wainwright, Chief of First Corps Artillery. The cranky upper-class Wainwright, from Dutchess County New York, became fast friends with the Bostonian doctor. Wainwright kept an extensive war-time journal, most of which has been published. He mentions Medical Director Heard several times. Here are some excerpts. “This morning I rode around by the river, where we are to cross, with Dr. Heard, who I find to be a most pleasant, gentlemanly companion. At "White Oak Church" we took a road which leads directly down to the river.” - Wednesday, December 10, 1862. In a passage dated August 9, 1863, Colonel Wainwright reflected on the health of the troops and the skill of the medical department. “The troops continue very healthy so far; very much more so than they were last year at this time in any part of Virginia. This is owing to many reasons. The season is very different, this year being dry, while last was a constant pour. ...But the main reasons for the better health of the army lie in the facts that the men themselves as well as their officers have learned how to take proper care of themselves, and that our medical staff is infinitely superior to what it then was. ...The medical staff has changed vastly from what it was a year ago; fully one-half of the old regimental surgeons have been sent home, and better ones come out in their place. Those that had brains enough to hold their commissions have learned their duties, the business part of which was totally new to every one of them, as well as the different mode of treatment required for troops in this climate from that needed by people living in houses farther north. “...The men have a good time of it bathing in the river this warm weather. Bache and Heard propose that we should go down and have a swim some time if it is possible to find a spot out of sight of the men, which is not likely.” Dr. Heard's family was of a high social standing, and his diary mentions that at one time in 1864, he attended the theatre with President Lincoln. Colonel Wainwright records another anecdote of Dr. Heard during the Army of the Potomac's winter encampment at Culpeper that same year. “General Rice, commanding our First Division, has had a bevy of girls at his headquarters, a private theatre and what not. Heard says he was over there once or twice, and tells a good story of his mother when giving her name to a shop girl in Baltimore being asked if she was any relation to Dr. Heard of the First Corps, who the shop girl said she knew very well, having met him during her visit to General Rice, int the army. Imagine Mamma's disgust, she having just social standing enough to feel such a thing...” - Culpeper, Feb. 29, 1864.

At Gettysburg, Colonel Wainwright (pictured) noted the capture of his friend, and then his welcome return on July 4th. “The loss of the corps today is put at 7,000, some 3,000 of them being sound prisoners, captured at the last charge, and stragglers picked up in the town. All our wounded, and nearly all our surgeons, were prisoners in the town, including Heard and Bache, and my own little doctor.” - July 1, 1863. “July 4, Saturday. As usual, we were up by daylight this morning, but it was not ushered in by a volley of cannon and musketry as it was yesterday. On the contrary, our pickets in the outskirts of the town soon reported that there was no enemy in their front. Very soon after I saw Heard and Bache trudging up the hill on foot, and joyfully went down to meet them. They said that the rebels had withdrawn from the town during the night, their pickets just gone at daylight. How far they had gone, they did not know. All our severely wounded of the first day and those of the enemy were left in the town, as also all the surgeons of the First and Eleventh Corps who were caught there on our falling back. They only stopped with me a minute or two, and then went on to report to General Newton and General Meade. More anecdotes of the doctor come from a lengthy article by George Edward Jepson, Co. A, printed in Thirteenth Massachusetts Regiment Association Circular #17, August 1904. “Among the members of the latter’s [Major-General John F. Reynolds] military family was Dr. J. Theodore Heard, a well-known physician of Boston at the preset time, and our esteemed regimental surgeon formerly. Doctor Heard was called to Army Headquarters at Frederick City, Md., early one morning and there learned that Hooker had just been relieved and the command turned over to Meade. On his way back to the head-quarters of the First Corps he met General Reynolds, and thinking that he (the general) was ignorant of the change in commanders, told him of the surprising fact. General Reynolds received the statement with a placid smile and, nodding his head, said shortly, “I know it.” He turned abruptly away, however, as if to avoid any discussion of the event. It was about this time that the rumor was whispered about that the command of the army had been offered to Reynolds. The personal peculiarities alluded to as so remarkably distinguishing the general forbade any comment on the subject in the latter’s presence. A more extraordinary instance of his self-restraint and extreme delicacy of feeling is furnished by the sequel.

In the Spring of 1864 Dr. Heard passed a part of an evening with President Lincoln and casually mentioned the rumor concerning Reynolds. The President asserted positively that it was true, adding also that General Reynolds had not only declined the high honor, but had strongly recommended General Meade for the position, the presumption being that Reynolds’ recommendation had been sufficient to settle the matter. The extraordinary point of the incident is that, so far as known, Meade remained in ignorance of it to the day of his death.” Jepson's deductions may or may not be accurate but the anecdote is true. Another is related in the same article. “…Doctor Heard, during the conversation previously referred to, related to the writer an interesting incident that had a significant bearing on the point in question. The doctor was in the town attending to the wounded when Hill’s and Ewell’s troops came surging in. footnote “A little later, while consulting on the battlefield with Gen. A.P. Hill, the Confederate corps commander, about caring for the wounded the latter, looking at the many caps of the Union soldiers that strewed the ground, observed in a tone of surprise, “Why I see you had the Third Corps here as well as the first and Eleventh!” “Now the Third Corps badge was a diamond shaped piece of cloth, while that of the First Corps was in the form of a sphere or lozenge.The latter through hard service had in some instances shrunk or become partially detached from the cap and lopped over in such a way as to present something of the appearance of a diamond. In the fading light, and without close scrutiny, it was not remarkable that Hill was deceived and took it for granted that a large part of Meade’s army was at hand than the rebel leaders supposed to be the case.” “Doctor Heard with quick apprehension of Hill’s mistake did not feel called upon to undeceive him, however, particularly as the rebel general by his tone and manner indicated that he was quite satisfied of the correctness of his surmise. Its nice to have these little glimpses into

Surgeon Heard's

military life, as I have very little mention about him considering his

impressive career. When the army was re-organized by General

Ulysses S. Grant in 1864, the diminished First Corps was consolidated

into the Fifth Corps, and Surgeon Heard lost his post. Not

long

after, he was appointed Medical Director of the 4th Army Corps, Army of

the

Cumberland in which he saw service with General William T. Sherman.

The following brief bit about Surgeon Heard was

published in the 13th Regiment Association Circular #19, December, 1906. John Theodore Heard was born in Boston, May 28, 1836, the son of John Trull Heard and Almira Patterson, both of Boston. He died at his summer residence in Magnolia, Mass., Sept. 2, 1906. He was educated in the Boston Latin School and at the Harvard Medical School, graduating from the latter institution in 1859. He then entered the Massachusetts General Hospital as an intern, and completed his service in the hospital in that capacity. Subsequently he studied abroad in Dublin and Paris. He was married, Oct. 28, 1868, to Rosalie I. Gaw, of Philadelphia. He continued in the active practice of his profession for about three years after his marriage, and was one of the surgeons in the out-patient department of the Massachusetts General Hospital. While he was abroad, pursuing his medical studies, the news of the firing on Fort Sumter reached-him and he decided at once to return home and offer his services to his country. One of his classmates in the Latin School says: "The news of the firing on Fort Sumter reached my brother John and me at Seville at sunset; we took the early morning train for home by way of Paris, arriving at the Gare de Lyons with only half a franc in our pockets, for we could not stop anywhere to draw money on our letter of credit. The next morning, after a call on our bankers, we hurried to the Cunard office and bought the two remaining state rooms on the Cunarder 'America.' A moment after, in burst Theodore, and when told that the last state room had just been taken, said, 'Then give me a second cabin ticket.' When told there was no second cabin on the 'America,' he instantly said, 'Then I go in the steerage rather than wait over.' "Then I tapped him on the shoulder and asked him where he came from in such a tearing hurry. He replied, 'I was in Moscow when the news reached me and I have come night and day to get here.' We said, 'The same with us in Seville,' adding that we had taken the last remaining state rooms 'so that no secessionist shall have an extra state room, but as you are not of that type, it is yours.' So we went home together with a crowd of others like ourselves, seeking not military glory, but to do our best for our country's sake."

Dr. Heard was mustered in as assistant surgeon, Thirteenth Massachusetts Infantry, July 16, '61; mustered out as surgeon, Oct. 25, '65; promoted to surgeon, U.S. Vols., May 1, '62; brevetted lieut-col., March 13, '65; May 1, '62, assigned as brig.-surg., 1st Brig., 2d Div., 1st. A.C. (then Duryea's brigade of McDowell's Corps); Oct. 28, '62, assigned as surg.-in-chief, 2d Div., 1st A.C.; Nov. 10, '62, assigned as medical director of the 1st Corps, Army of the Potomac, commanded by Gen. John F. Reynolds, remaining in that position until the 1st Corps was consolidated with the 5th Corps under Gen. Warren, March 23, '64; March 25, '64, assigned as surg.-in-chief of artillery reserve, Army of the Potomac; April 30, '64, assigned as medical director, 4th Corps, Army of the Cumberland; promoted to lieut.-col. by act of Congress (dated Feb. 25, '65), March 13, '65. In this concise statement of his military career is embodied four years of the hardest kind of service to a sympathetic nature such as his. The duties of surgeons in the army were often performed under circumstances heart-rending, particularly during the excitement of battle, where the courage of a surgeon underwent the severest test, and where coolness, gentleness and patience were of the highest importance. These qualities Dr. Heard possessed in a high degree, and are amply confirmed by reports and by the verbal testimony of those with whom he had the honor to serve as a staff officer. The young army surgeon of to-day can scarcely realize or appreciate the comparatively meagre facilities surrounding the field hospital of the Civil War, or the difficulties encountered in administering to the sick and wounded or supplying their needs and wants with comforts necessary to a rapid restoration to health. He joined the Thirteenth Massachusetts Infantry at Fort Independence in July, 1861, and was at once recognized as a man of refinement and culture. Though modest and unassuming to a very unusual degree, he soon acquired, by reason of his dignity, his sweetness of temper and simplicity of manner, the love of the men of his regiment, who took pride in his valor and the abilities he manifested during his service as a medical director of the First Army Corps. To write at any length of his services during the war would be difficult for any man, even his most intimate friend. He was extremely reticent about his own service, preferring to be classed among those who, having performed the duty assigned them, see no reason for glorifying it by advertisement, or enlarging upon it any more than upon any other contract they undertook to perform. His service, therefore, can be summed up in a very few words. He was a meritorious officer, acquiring distinction by his abilities and by the faithful and diligent performance of his duties, and by his life and actions did the biggest of all things, made his regiment respect and like him. C. E. DAVIS, JR. 'The Christian Commission'BOSTON EVENING TRANSCRIPT July 8, 1863. THE SUBSCRIPTION OF

BOSTON in answer to the appeal of the

President of the Christian Commission has been prompt and very liberal.

At two o’clock this

afternoon, upwards of

Twenty

Thousand Dollars had been contributed, and

further

donations were

being received. Pictured below are the field offices of the Christian Commission at Camp Letterman, Gettysburg.

Charles Davis Jr., chose to concentrate on the characteristic slowness of the Army of the Potomac, rather than the horrors of the battle-field in his narrative for the regiment on July 4th. But he did not ignore the solemnity of the time. For his narrative of July 5th, he chose to quote from an officer in the Christian Commission to convey the un-speakable scenes around Gettysburg after the armies dis-engaged. The following is from "Three Years in the Army, The story of the Thirteenth Massachusetts Volunteers from July 16, 1861 to August 1, 1864." by Charles E. Davis Jr. Boston, Estes and Lauriat, 1894. Pages 247-248. Sunday, July 5. At daylight it was announced that the Confederate army had retreated. At 9 o’clock the regiment was moved to the left of the line to a position lately occupied by the Third Corps. Burying parties were now busily employed to bury the dead, from whose bodies the stench was almost intolerable. The following is an extract from a letter written for the Christian Commission by Mr. R. G. McCreary, a prominent citizen and lawyer of Gettysburg, who was an eye-witness of the scenes he describes: “The battle of the 1st of July commenced about the middle of the forenoon between the rebels advancing on the Chambersburg turnpike and Buford’s cavalry who, as the infantry of the First Army Corps came up and formed in line of battle, slowly retired to the rear. The approaching storm was watched with intense anxiety by the citizens, but it was not long until the boom of cannon, the bursting of shell, the rattle and crash of heavy infantry firing along the ridges west of the town, and the streams of litters which began to move in from the field of carnage, brought them to realize the fact that a fierce and bloody contest was in progress.

I saw no more of the battle till the middle of the afternoon, though there was abundant evidence in the many mangled forms coming in, upon whom I was tending, and the louder and increasing crash of arms, that the conflict was a most terrible one, and was rapidly approaching the town. At length, by the frequent explosion of shells in the immediate neighborhood, I found that our army was falling back, and soon the rush and roar in the streets banished everything else from my mind. That was a terrible night. Our army had been driven back; the town was full of armed enemies. We saw and heard the progress of pillage all around us. The morning of July 2d revealed a dreadful sight – dead horses and dead men lay about the streets, and there were none to bury them. Our first care was for the multitude of wounded men now suffering for the want of food. The bakeries were in the hands of the rebels, and not a loaf nor a cracker remained; the butchers’ cattle had been driven off or confiscated, and no meat could be procured; the groceries were broken open, and their contents carried away or destroyed by troops of rebels, who, like hungry wolves, roamed through the streets in search of plunder. The rebel officers, until Friday (July 3), seemed to be entirely confident of success. One of them said to me on the forenoon of Thursday that they would not remain with us more than a few hours, as General Lee had his plan of battle nearly arranged, and they would move forward, and he seemed to think with assured success; they extolled General Lee as the great master of the military art, and spoke of his admirable strategy in making a grand feint toward Philadelphia in order to concentrate his army here for an attack on Baltimore and Washington. About this time a squad of soldiers passing were halted, and asked to what they belonged? They replied, “To the Second Louisiana Brigade.” They were then asked if they had taken a battery they had been charging upon? And they replied that they had “To come out,” and could not take it. The officers were silent. These men said the next day that they had but fifty men left in their brigade after that assault. They were the “Louisiana Tigers,” of whom those officers had boasted that “they had never been driven back in a charge, and never would be.”

On Friday night

and Saturday morning

the rebel army had withdrawn from the town to the crest of Seminary

Ridge, and our skirmishers had driven out or captured their stragglers

and pickets. While the dead still lay unburied and the

helpless

wounded upon the field were numbered by the thousands, the call of the

bugle summoned the victors from the side of the dying, the faithful

surgeon from the pierced skull, the mangled flesh, and broken

limb. Saturday, Sunday, and Monday, the town of

Gettysburg

presented a woeful appearance. Guns were scattered in the

streets

or piled upon the sidewalks. Pavements were stained with

blood. Every church and public building, and in fact almost

every

private house, was filled with wounded. More than twenty

thousand

wounded men were in and around Gettysburg.” Next Page: "The Field Hospitals" Return to Top of Page | Continue Reading |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

© Bradley M. Forbush, 2017 Page Updated January 11, 2017.

|

Fay and I now

thought if we did not wish to starve we

must

find the regiment, so we started keeping a good watch of everything by

the way. We hadn’t gone more than half a mile when we saw a

colored individual that we knew that belonged to the regiment, [and] we

enquired of him if he knew where it was. He said it

was up

by the village, that the teams had just been up to issue rations and

that they were only a little ways from here. This was good

news

for us, and we went on keeping a good lookout for all

teams.

Fay and I now

thought if we did not wish to starve we

must

find the regiment, so we started keeping a good watch of everything by

the way. We hadn’t gone more than half a mile when we saw a

colored individual that we knew that belonged to the regiment, [and] we

enquired of him if he knew where it was. He said it

was up

by the village, that the teams had just been up to issue rations and

that they were only a little ways from here. This was good

news

for us, and we went on keeping a good lookout for all

teams.

Corporal

Bradford with

others, rendered timely aid to many

of the wounded inside the rebel lines.

He found Captain Lowell of Company D, where he

fell mortally wounded, a

short distance from the Mummasburgh road, and near the

stone-wall. Although conscious, he was

speechless. He was

carried to a vacant room in the

seminary, on the first floor. Before

Bradford

could find a surgeon, he, with others, was marched

to the rear some two miles. Corporal Bradford adds, that when he found

Captain

Lowell he had been robbed of all valuables, and the absence of papers,

and a

small diary torn up and scattered, made it impossible for strangers to

identify

the body, hence his burial place is unknown. While in the slough of

despond,

and trying to assist as skirmishers in the front line, Major Leavitt

joined the

regiment, and assumed command at ten o’clock P.M.

The heavy rain could not put out our

enthusiasm, or dampen our joy at his coming. While lying here, Sergeant

Morrill, of Company A, was mortally wounded in the breast, by a

sharp-shooter.

Corporal

Bradford with

others, rendered timely aid to many

of the wounded inside the rebel lines.