A Change in Plans

May 12th - May 28th 1862

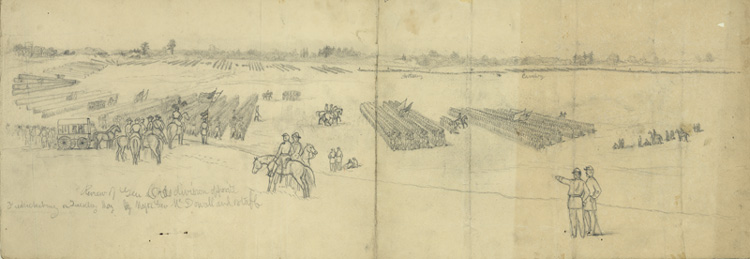

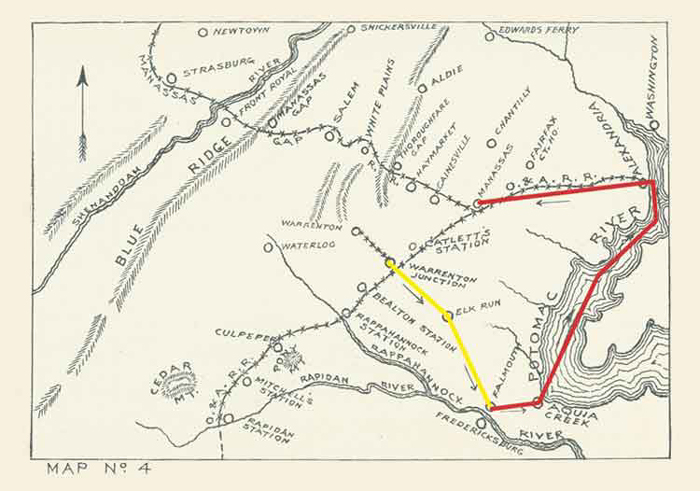

This map from the

Regimental History illustrates the movements of the regiment May 12th -

May 15th (yellow).

Lincoln's order of May 24th necessitated the change

in direction of

General McDowell's Corps (red).

Table of Contents

- Introduction

Introduction

President

Lincoln’s relationship with General

George B. McClellan deteriorated in early 1862 over McClellan’s

apparent inaction. Lincoln favored an assault on the

Confederate

fortifications close by Washington at Manassas. General McClellan

believed

Manassas

was too strong to attack.

President

Lincoln’s relationship with General

George B. McClellan deteriorated in early 1862 over McClellan’s

apparent inaction. Lincoln favored an assault on the

Confederate

fortifications close by Washington at Manassas. General McClellan

believed

Manassas

was too strong to attack.

In January the newly formed Committee on the Conduct of the War, a political body hostile to McClellan, put pressure on Lincoln to learn the General's plans or force him into action. McClellan remained silent. On January 13th McClellan reluctantly attended a cabinet meeting and sullenly stated that he knew what he was doing, the President couldn’t be trusted to keep a secret, and that the army of the west would move soon.

In February the general finally revealed his strategy to Lincoln. He planned a massive advance upon Richmond, the Confederate capital, by way of Urbanna, before the city could be reinforced with a large army. Lincoln was skeptical and still preferred an assault on Manassas.

On March 8th, a week after General N. P. Bank’s Corps advanced into the Shenandoah Valley from Williamsport, Md., the Confederate force near Washington abandoned Manassas and moved their defenses south to the line of the Rappahannock River closer to Richmond. Washington troops occupied Manassas and embarrassingly revealed the position had been held with fake guns, and a much smaller force than estimated; 36,000 men. Lincoln was furious. McClellan’s force was 120,000 strong. McClellan was demoted from General in Chief of the Army to Commander of the Army of the Potomac. General Henry Halleck replaced him as Commander in the west.

McClellan’s new plan, endorsed by his

Corps

commanders, was to sail around the Rebel defenses to the Peninsula and

besiege Richmond with his huge army of 150,000

men. Lincoln

agreed but insisted McClellan provide 40,000 troops for the defense of

Washington. Lincoln painfully remembered the two week in April 1861

when Washington was cut off from the army, undefended and vulnerable

to a

Confederate assault.

McClellan’s new plan, endorsed by his

Corps

commanders, was to sail around the Rebel defenses to the Peninsula and

besiege Richmond with his huge army of 150,000

men. Lincoln

agreed but insisted McClellan provide 40,000 troops for the defense of

Washington. Lincoln painfully remembered the two week in April 1861

when Washington was cut off from the army, undefended and vulnerable

to a

Confederate assault.

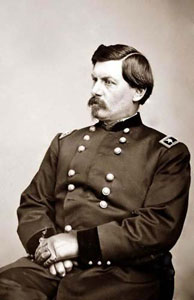

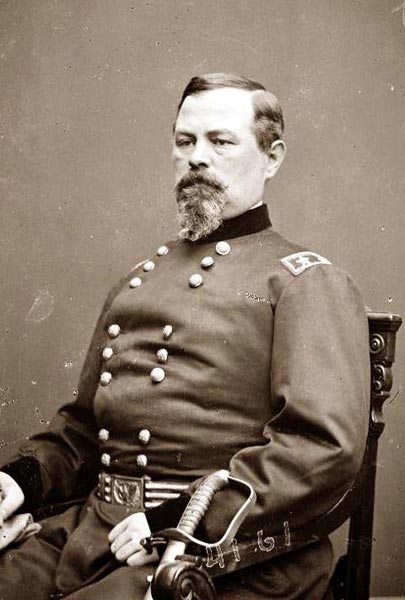

McClellan complied but the troops reserved for the defense of Washington were spread out; 19,000 in Washington, 10,000 at Manassas, 8,000 at Warrenton (including the 13th Mass) and 35,000 in the Shenandoah Valley. Lincoln’s advisors didn’t understand the strategy and McClellan had angrily left Washington without explaining it. Lincoln’s loss of faith in his leadership bothered the General who correctly viewed the political forces in Washington as his enemies. McClellan’s political support failed when he needed it most. Seeing only 19,000 ill-equipped troops around Washington, the President withheld General Irvin McDowell’s corps of 35,000 men from McClellan to guard the capital. Total troops withheld by the President reduced McClellan’s invading force down from the intended 150,000 men to 100,000 men. General McClellan thought his plan ruined and his chances for success greatly reduced even though he still outnumbered the Rebels by huge margins.** [photo of General McClellan from old-picture.com]

By mid May General McDowell was moving his newly re-enforced Corps of 41,000 troops, including the 13th Mass, to link up with McClellan’s army outside Richmond.

“It was understood that McDowell was to

move his

corps along the Fredericksburg and Richmond Railroad on the 24th of

May, connecting, if possible, with the right wing of McClellan’s army

at or near Hanover Court-House, and by turning the left flank of the

enemy, prevent his receiving reinforcements from the direction of

Gordonsville. This plan had been carefully considered and matured by

McDowell, who had great faith in its success.” (Three Years

in

the Army, by C. E. Davis, Jr.)

“It was understood that McDowell was to

move his

corps along the Fredericksburg and Richmond Railroad on the 24th of

May, connecting, if possible, with the right wing of McClellan’s army

at or near Hanover Court-House, and by turning the left flank of the

enemy, prevent his receiving reinforcements from the direction of

Gordonsville. This plan had been carefully considered and matured by

McDowell, who had great faith in its success.” (Three Years

in

the Army, by C. E. Davis, Jr.)

General Shields 10,000 men were also en route to Fredericksburg, detached from General Bank’s force in the Shenandoah Valley.

Confederate General Robert E. Lee anticipated and feared this build up and wrote General 'Stonewall' Jackson to create a diversion in the Shenandoah Valley to draw off some of McDowell’s troops. Lee sent General Ewell to the Valley to re-enforce Jackson. The diversion worked.

Banks' small force of 9000 men was divided at 3 outposts. Jackson attacked and defeated one of these at Front Royal on May 23rd. The next day President Lincoln ordered General McDowell to send 20,000 troops to the valley in hopes of catching Jackson. This change in plans greatly distressed General McDowell. He protested that much would be lost and little gained. General Banks was beyond his help and the best thing McDowell could do was continue towards Richmond to threaten Confederate forces there. Nonetheless, McDowell complied with Lincoln’s order. The 13th Mass, in Hartsuff’s Brigade was included in the force diverted to Front Royal. [photo: General Irvin McDowell from the National Archives].

These political machinations and movements were beyond the scope of the men in the 13th Mass. All they saw was the increased hardship imposed on them by General McDowell’s orders; the loss of baggage wagons and camp equipments that made life more comfortable for them, and constant drilling with full gear in temperatures near 100 degrees Fahrenheit. They compared the progress made on other war fronts with the supposed inaction of McDowell whom they labeled Mc-Do-Nothing. He was credited with each new hardship and they developed an intense dislike for him.

** Referenced from Larry Tagg's book "The Unpopular Mr. Lincoln."

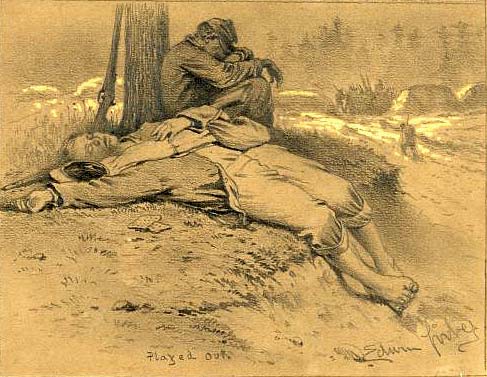

Picture credits: All of the images on this page come from the Library of Congress Digital Collection with the folllowing exceptions: The sepia-tone images of Gen. McClellan & Gen.McDowell are from the site old-picture.com. The sketch of Gen. Hartsuff is from a digital archive of images from Frank Leslies Illustrated; the image of Col. Fletcher Webster is from the Mass. MOLLUS collection at the Army Heritage Collection on-line at Carlisle, PA. The Forbes sketch "Played Out" has been cropped in photoshop and adjustments have been made to its contrast. The 'quinine' label is a fabrication created in Photoshop.

A

Hard March South; Warrenton Junction to Falmouth

From the Regimental History, "Three Years in the Army" by Charles E. Davis, jr.

On May 11th orders were issued by General Hartsuff to march the next day. The following paragraphs appeared among other items:

Tents will be struck, the baggage-wagons loaded, trains straightened out, and the regiments formed under arms in marching order, on their respective parade grounds. Companies will then be quickly inspected by the captains, under supervision of the colonels. Cartridge-boxes and canteens will be full, and at the signal, the line of march will be taken up.

During the march no straggling will be permitted. The march at starting, and after each halt, will be in close order, at "shouldered arms," until the column is in motion, when the command "route step," given from the head of the column, will be rapidly repeated to the rear. Captains will fall to the rear of their companies, leaving a lieutenant in front, and will see that none of their men leave the ranks without written permission, for which purpose each will prepare before-hand a number of slips of paper, or a little book. If a solder leaves the ranks temporarily for a necessary purpose, his arms and equipments will be distributed amongst and carried by his set of fours until his return. The rear-guard will take into custody all stragglers without permission, and will turn them over to the provost marshal after arriving in camp.

Monday, May 12.

Hot

day. Uniform

coats were packed and sent to Boston, except in those instances where

they were thrown away. Once again our knapsacks had grown fat

with camp life, and had to be trained down. The gossip of the

camp said the orders were “On to Richmond.” In spite of the

explicit directions of yesterday, there was a good deal of confusion in

camp, due to packing and sending superfluous baggage home.

We got away at last and marched to Elk Run, six miles, where we bivouacked. During the night General McDowell came through the picket line from Fredericksburg. On this moonlight night, General McDowell, with a large retinue, halted quick enough, but his delay in giving the countersign might have cost the life of himself or one of his attendants. A general ought to know better.

Thursday,

May 13.

Thursday,

May 13.

About six

o’clock we took

up the line of march toward Falmouth, halting late in the afternoon,

after tramping eighteen miles. The heat, which was above one

hundred degrees, with a bright sun and not a breath of wind, was so

intense that both men and horses dropped to the ground overcome by it.

On no march, before or after, were the men so terribly

affected as on

this occasion. For more than a dozen miles, the road on

either

side was ornamented by the prostrate bodies of men who were unable to

keep along. More than fifty cases of sunstroke in the brigade

were reported, while only seventy-five of our regiment reached camp at

the end of the march. After dark the balance of the regiment

straggled

into camp, so that by roll-call in the morning nearly all were

present. One of the reasons given for making the march so

long

was the difficulty of finding water suitable and in sufficient

quantities to supply the brigade. We were in no condition for

marching,

after more than a month of comparative idleness in a swamp where the

physical condition of the men had become more or less affected by our

malarial surroundings.

Wednesday, May 14.

At 7 A.M.,

in rain and

mud, we resumed our march through Falmouth, halting near General

McDowell’s headquarters, about eight miles from our starting

point. Here we waited two hours in the rain before the

regimental

wagons arrived. In the meantime we settled the responsibility of

yesterday’s work by placing the blame on McDowell, notwithstanding the

question of water was said to be the real cause of our lengthened march.

The occasions when a ration of whiskey

was issued

to a brigade were very rare. General Ord was convinced,

however,

that on this particular day the condition of his men would be improved

by it, and we were thereupon ordered to fall in line for that

purpose. A large majority of the boys believed that nothing

ought

to interfere with putting down rum, but insisted that it should go,

like all communications to or from the Government, “through the proper

channel.” There were some among us, however, who, while

apparently possessing the same belief, “down with rum,” differed very

radically as to the manner of putting it down, as one of their number

on receiving his ration, immediately turned it on to the ground; a

proceeding that excited a howl of indignation, not at the waste of the

material, but at so gross an act of insubordination in disobeying the

order of his superior officers, who expected him to drink it.

The occasions when a ration of whiskey

was issued

to a brigade were very rare. General Ord was convinced,

however,

that on this particular day the condition of his men would be improved

by it, and we were thereupon ordered to fall in line for that

purpose. A large majority of the boys believed that nothing

ought

to interfere with putting down rum, but insisted that it should go,

like all communications to or from the Government, “through the proper

channel.” There were some among us, however, who, while

apparently possessing the same belief, “down with rum,” differed very

radically as to the manner of putting it down, as one of their number

on receiving his ration, immediately turned it on to the ground; a

proceeding that excited a howl of indignation, not at the waste of the

material, but at so gross an act of insubordination in disobeying the

order of his superior officers, who expected him to drink it.

We found the whiskey was

highly

impregnated with

quinine, but as some of the boys remarked, “the whiskey was

there.” It is wonderful how this terrible enemy of mankind is

able to warm so effectually the cockles of the heart, and make the

dreariest weather seem as soft and mellow as a summer’s day. We

commended General Ord very highly for this evidence of his intelligence.

Thursday, May 15.

Rained hard all

day. The

rain was unnecessary, except to deepen the mud, which it admirably

succeeded in doing.

Letter of Edwin Rice, 13th Mass Band, May 16th.

Falmouth, Virginia

May 16th 1862

Viola,

Yours of the 10th was received Monday eve. We left Warrenton Junction Monday about noon, marched 6 miles and pitched camp for the night. Weather was pleasant and pretty warm. Your letter was handed me just as I was going to bed, also one from Sid Learing. I went to sleep about 8 o’clock and slept pretty sound. Shouldn’t think I had been asleep over an hour when I woke up and heard the reveille beating. Got up and found out that it was 5 o’clock in the morning. Started on the march again at 6 o’clock. We marched that day 17 miles over the worst roads that I ever saw. McDowells Division passed over them two or three weeks before and the wagons cut the road up very badly.

We should not have marched so far that day if we could have found water enough for the brigade. Water was very scarce on the road. The day was pretty warm and a good many men fell out on the march. There are 7 men missing now out of our regiment. It is said we passed within 100 rods of a rebel cavalry company. Perhaps they took some of the straglers prisoners. Wednesday morning we started about 7 o’clock. The sky was cloudy, but did not look as though it would rain.

With the exception of 4 or 5, the Band put their blankets and overcoats on our wagon. It rained a little all day long. We got onto our campground about noon. The wagons did not come up till about 4 o’clock. By that time we were wet through. Made ourselves pretty comfortable as soon as the tents were up.

There are stories in camp today that when we leave this camp, we leave the tents behind and that only 5 teams will be allowed the regiment. The usual number is 20. Rubber blankets are to be furnished us. Two of them put together with some sticks and pins that come with them will make shelter enough for two persons to lay in under. The officers are to have the same as the men.

There is not a brigade in McDowells Division that have large tents except ours. If we who belong to the Band have any valises we shall have to carry them on our backs. Am going to send mine home. Also my overcoat and a grey blanket.

I have not had a chance to see Fredericksburg yet. Cannot get across the river without a pass. Falmouth is not much of a place. We are about a mile and a half from the river.

The country between Warrenton Junction and this place is level, thickly wooded and very thinly settled. There was not a village in the whole distance – 33 miles. I received a letter from Mother yesterday morning mailed the 12th.

I was pretty well tired out when we halted Tuesday night. Was not feeling very well when we started in the morning. Am as well now as ever.

Hope that the next march that we make will be toward Massachusetts. When you direct letters to me do not put on any general’s division. Nothing but the brigade (General Hartsuff).

Edwin Rice

Friday, May 16.

The following order was received:

Headquarters Department of the

Rappahannock,

Opposite Fredericksburg, Va., May 16, 1862.

General Order, No. 13.

A division to be composed of Brigadier-Generals Ricketts’ and Hartsuff’s brigade of infantry and Brigadier-General Bayard’s cavalry brigade is hereby formed, to be commanded by Major-General Ord, who will immediately proceed to organize the same…

By command of Major-General McDowell.We took a great fancy to General Ord, though we still looked foreword to our return to General Banks.

An order was received to make requisition for “shelter” tents. The Eleventh Pennsylvania joined our brigade to-day.

Hartsuff's Brigade

Hartsuff’s

brigade, as now

formed, consisted of the Ninth New

York (scheduled as the Eighty-third Volunteers). The Eleventh

Pennsylvania, and the Twelfth and Thirteenth Massachusetts, and these

regiments continued together in the same division during the remainder

of our service, and for many months we were together in the same

brigade, an unusual circumstance, we believe.

Hartsuff’s

brigade, as now

formed, consisted of the Ninth New

York (scheduled as the Eighty-third Volunteers). The Eleventh

Pennsylvania, and the Twelfth and Thirteenth Massachusetts, and these

regiments continued together in the same division during the remainder

of our service, and for many months we were together in the same

brigade, an unusual circumstance, we believe.

It is with great pleasure that we are

able to speak in terms of

admiration of the uniform kindliness that existed among those old

regiments. There grew up, among the offices and men, a warm

feeling of

attachment. Probably the fame it acquired was, in a great

measure, due to the harmony that continued so long undisturbed. There

were no bickerings or quarrels, and whichever regiment had the advance,

a feeling of reliance was felt that near by were men who were watching

for an opportunity to aid with their assistance a doubtful

moment. It always happens that when solders have been long

together, they acquire a confidence and faith in each other that makes

their service of great value in important exigencies.

The Eighty-third New York Volunteers was the “Ninth New York National Guard” composed of a superior class of men, whose homes were in New York City. It was one of the old militia organizations of the State, and was among the first regiments to volunteer for three years. The esprit de corps which it showed in retaining its old number, “The Ninth New York,” in spite of the number assigned by the Government, indicates the pride felt in the record it had made prior to the war. It was commanded by Colonel Stiles. (Colonel Stiles is pictured top, right; Library of Congress photo).

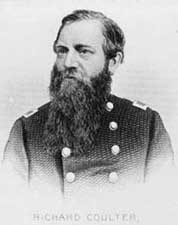

The Eleventh Pennsylvania was

another good regiment, raised

among the mountains of western Pennsylvania, and was commanded by

Colonel Richard Coulter, than whom a better fighting man never lived.

He was beloved by his old regiment, as he was by every officer and man

in the brigade.

(Colonel Coulter pictured at right; Library

of Congress photo).

The Eleventh Pennsylvania was

another good regiment, raised

among the mountains of western Pennsylvania, and was commanded by

Colonel Richard Coulter, than whom a better fighting man never lived.

He was beloved by his old regiment, as he was by every officer and man

in the brigade.

(Colonel Coulter pictured at right; Library

of Congress photo).

The Twelfth Massachusetts, commanded by Colonel Fletcher Webster, was in no way inferior to the others. It was nearer related to us than either of the others, being raised in the same community. By reason of this fact, our associations were more intimate, and as it has been our fortune to meet its members more frequently since the war, the attachment has flourished. To read the history of either of these regiments, is reading our own story. Each had some qualifications that attracted the admirations of the other. If the Eleventh Pennsylvania called us the “Bandbox Guard,” we laughed, for we knew it contained no reflection on our courage, but had reference to our taste for prinking, which we indulged to some extent during the early part of our service. Our battles, marches and picket duty we shared together for many months. (Photo courtesy Army Heritage Education Center; Mass MOLLUS Collection)

General Ord Assumes Command of the Division

Saturday May 17.

Moved camp in the afternoon, about

three miles on the road to White Oak Chapel; a pleasant spot.

General Ord assumed command of the division.

Sunday May 18.

Religious services. The entire

brigade being in attendance, it made a fine appearance, sitting on the

grass.

Company D ordered to report to General Ord as body-guard.

This National Archives Photo depicts

General Edward O. C. Ord & Staff

Letter of Warren H. Freeman, Company A, May 18th.

Falmouth, VA., May 18, 1862.

DEAR FATHER, - We left our camp at Catlett’s Station last Monday afternoon, and marched about six miles and camped for the night. We pitched our tents, but as it was very warm four of us preferred sleeping outside; we fixed our rubber blankets so as to keep the dew off, and turned in. We took up the line of march at about six o’clock the next morning, and at four o’clock P.M. we had made seventeen miles. I tell you it was terrible hot ; several of the men were sunstruck, and four horses died on the road.

Out of the three regiments of infantry in our brigade, I don’t think more than four hundred men came in. I never saw so many fall out before; some threw away their blankets, overcoats, rations, etc. However, by midnight nearly all the stragglers came in. When the teams arrived we pitched our tents and prepared our supper; after this I went to a brook near by and took a bath ; this, with a good night’s rest, made me all right.

We started at seven o’clock the next morning and marched to Falmouth, seven miles. It rained about all the time ; but this was not so bad as the burning sun of the previous day. On arriving at Falmouth we found no convenient camping ground, so we had to proceed about two miles further before we could be accommodated in this respect; then we had to stand about two hours in a drenching rain before the wagons with our tents came up. On their arrival, with the aid of our stoves, which fortunately were not left behind, we made ourselves as comfortable as the nature of the case would admit. From these brief details you can form some idea of the hardships of a soldiers’s life.

We are now in McDowell’s Corps ; and I learn there is to be a new order of things ; he intends taking away our tents and substituting the smaller ones, such as the men carry on their backs. There are to be but five wagons to a regiment ; the officers are to give up their trunks, and we are to be cut down in every way – brought to a level with the regular army.

Fredericksburg is quite a large city, I judge from its appearance from our camp.

There are the remains of three burnt bridges in view. We have got the two pontoon bridges across now, and there is a railroad bridge almost finished. The river is quite wide, and deep enough for small steamers. Three of us got a pass and went down to the river fishing, did not have much luck ; caught a dozen smelts, some white perch, etc.

Two of our brigades are encamped on the opposite side of the river ; they have had their pickets driven in two or three times by the rebels who are in considerable force a few miles beyond the town.

I am in as good health as could be wished. Please excuse bad writing, etc., for I am in a very uncomfortable position for that purpose, seated on the ground with my knee for a table.

Warren

Corps Review

Thursday, May 20.

A review of the corps by General

McDowell and an imposing spectacle it was, with nearly 40,000 men in

line. The regiments were formed en masse, and as the field

was

not large enough, the extreme left was at right angle with the main

line. As our brigade was on

the left we had an excellent view of this

grand and imposing spectacle. General McDowell must have felt

proud as to the appearance of his command. As he rode down

the line, each regiment and detachment cheered him, until he reached

the Thirteenth, when he was met with silence. As already had been said,

we did not like him.

line. As our brigade was on

the left we had an excellent view of this

grand and imposing spectacle. General McDowell must have felt

proud as to the appearance of his command. As he rode down

the line, each regiment and detachment cheered him, until he reached

the Thirteenth, when he was met with silence. As already had been said,

we did not like him.

“We do not like you, Doctor

Fell,

The reason why we cannot

tell;

But this we know, and that

full well,

we do not like you, Doctor

Fell.”

According to our idea, he appeared to be very much wrought up at this evidence of our dislike. Whether this was true or not, every disagreeable order that followed from his headquarters was interpreted, in our conceit, as the result of this lack of demonstration on our part. Once possessed with this idea we took every occasion to give annoying expression to our feelings.

We had the honor of being selected as one of three regiments to show our efficiency in drilling. So far as drilling was concerned it was generally conceded that the Thirteenth could hold its own with the best regiments, as the colonel had drilled and drilled us in the most complicated movements, and he was a genius in that line. Only a master in the art of military drill would have dared to undertake, on an occasion of this kind, what he did with perfect confidence on that day. We were the last of the three regiments to march out. Having wheeled into line and presented arms, the colonel, in that clear voice which could always be heard the length of the line, without hesitation, called out order after order for thirty minutes without stopping to recover distances, if such were lost, until the last movement was made and we were marched off the field. We almost forgot our dislike for McDowell in the generous applause he gave us.

Artist Correspondent Edwin Forbes captured General McDowell's review in a sketch on May 20th. This Library of Congress drawing is titled "Review of General Ord's Division Opposite Fredericksburg."

Excessive Drilling

Wednesday, May 21.

In obedience to orders from General

McDowell we were drilled three hours a day in heavy marching order,

particular attention being given to marching. As we marched

down the

road, men from other regiments remarked that they preferred cheering to

drilling with knapsacks, conveying the erroneous impression that this

unusual duty was in consequence of our silence at the review.

As a

matter of fact, orders for this duty had been issued to the whole

corps, though it was some time before we were aware of it; in the

meantime we supposed we were an exception, and unjustly scored one

against McDowell.

Letter of James Ramsey; Company E, May 22nd.

May

22nd

1862

Opposite Fredricksburg

Dear Father

I received your letter the other day and this is the first opportunity I have had to ansere it as we are now under McDowell and he keeps us a drilling all of the time, and he is reviewing us every other day. Day before yesterday he reviewed the brigades under Gen Ord all of the troops cheered him with the exception of our brigade Some of Banks men like him, he has taken our tents from us and only allows 5 wagons to a regiment we had 20 I suppose the vision of wagons lost at Bull Run haunts him and he is determined to guard against it in future. I do not like Mcdowell I think he is trying to cripple Mc Clellan and Banks by withdrawing troops from their commands to lay idle at Fredricksburg although I think we will advance soon and there is some talk of our brigade having the advance on account of our being called the best brigade in the service On the review the 26th New York regt his pet regiment came out with white gloves on they made a better appearance on point of dress but our regiment beat them on drill and winded them I wonder what he thinks of the bandbox brigade as he call us with a sneer. We all like our new brigadier Gen he done all he could for us in trying to keep our tents. We had a battalion drill yesterday afternoon with knapsacks on, a drill with them on this morning

McDowell thinks we need to drill with them on so as to get used to fatigue. Why don’t some of his regts that never marched more than 30 miles get used to fatigue I think he is a traitor and is doing all he can to thwart McClellan’s plans. Yesterday I got a letter from John McCrillis and one from Ed Grey. They spoke of their intentions of joining the church I am glad to hear it I hope they are earnest about it. I was sorry to hear about Frank Anderson.

I do not know as I have got any thing more to write I am well and enjoying myself I stand the fatigue better than half the company I have kept up every march I must close

Give my love to all

From your son.

James.

Friday, May 23.

Thermometer 90 in the shade.

We were reviewed this afternoon

by President Lincoln, Secretary Stanton, and Secretary Seward,

accompanied by General McDowell.

Overcoats were packed and sent away. Clothing, shoes, ammunition, etc. issued to those of us in need of such articles.

The officers were growling

about the reduction of their

luggage,

proving the truth of what the Lord said unto Saul, "It is

hard

for thee to kick against the pricks."

Letter of Warren H. Freeman, May 23rd, 1862.

In Camp opposite Fredericksburg, Va., May 23, 1862.

Dear Father, - I wrote you from this place a few days since, and was not intending to write again so soon ; but there are indications that we are to make a forward movement soon, and I may not have another opportunity of writing. The weather is very warm ; we have a marching drill of two hours in the morning and two hours in the afternoon, in heavy marching order. We make about ten miles a day. Our general says it is to make us tough ; but we think we are tough enough to perform all the necessary labor that ought to be required of us, and that this extra marching only tends to break us down in body and spirit.

I have been overhauling my knapsack and throwing out everything I do not absolutely need. It now weighs eighteen pounds, and to this will be added an extra pair of shoes, and a shelter tent weighing five pounds. They are going to take away our Sibley tents and substitute what is called a "shelter tent" (or dog-huts, as the boys call them), and each man will be required to carry one on his back ; so that the labor heretofore performed by horses will now be transferred to the men. The new tents, are but a very poor protection against the weather, but McDowell is much opposed to a baggage train.

Five or six of our boys have put their overcoats into a box, mine with the rest, and sent them to Boston. We cannot carry them about with us, and have no place to leave them here. I have cut off the tails to my dress-coat and made a spencer of it. Coat-tails, Sibley tents, and overcoats now come under the head of luxuries which are not to be indulged in by private soldiers.

A few days since the whole of General Ord's Division was reviewed by General McDowell ; it was a gand affair. McDowell is a noble looking man, and fully competent to command this great army, numbering, the newspapers say, 60,000 men. But I don't know anything about the number ; it is a big army, I can safely say that. I never have seen anything approaching it in magnitude before.

Some think we are about to move on Richmond, to re-inforce McClellan ; others supose there is an army now before that city large enough to crush the rebellion as soon as the word is given. There is much speculation in camp about the mighty contests that must inevitably take place about these days ; and there is much going on in our immediate presence that leads me to suppose that we are not to be idle spectators in this terrible conflict of arms. But here comes an order for us to strike our big tents ; it is the last we shall see of them I suppose. So I bid you all farewell.

Warren

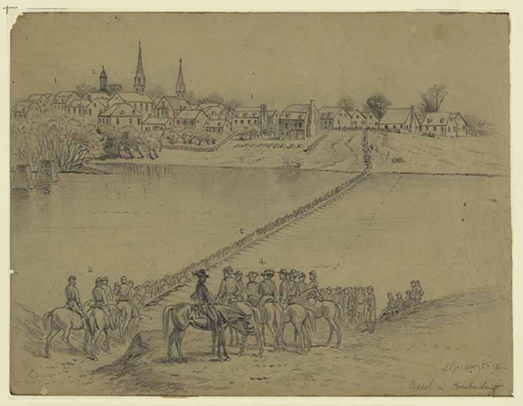

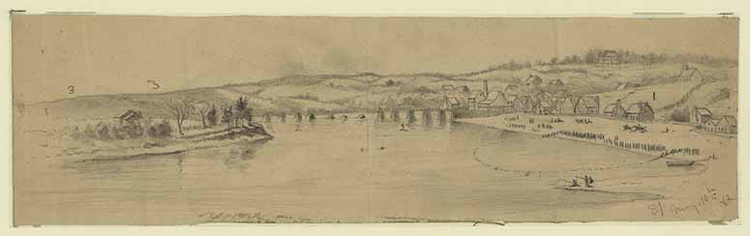

Picture Essay by Artist Edwin Forbes

Artist/War Correspondent Edwin Forbes followed General McDowell's army to Falmouth and Fredericksburg two weeks before the 13th Mass arrived. He did several pencil sketchs of the area in early May which are now in the collections of the Library of Congress. Since the regiment was camped in this immediate vicinity, I take the opportunity to present these rarely seen images. These sights would be familiar to the men of the regiment. Forbes post-war book "Fifty Years After; An Artist's Memoir of the Civil War" is well recommended for its depictions of army life and its commentary, from an artist who lived in the field with the soldiers. This picture dated May 5th, 1862 is captioned "Occupation of Fredericksburg; General McDowell's Corps Crossing the Rappahannock River on Pontoon Bridge."

"View of the Town of Falmouth, Va., looking up stream; May 10th 1862. Warren Freeman describes the river in his letter home on May 18th above. Three men can be seen fishing in the foreground of this sketch.

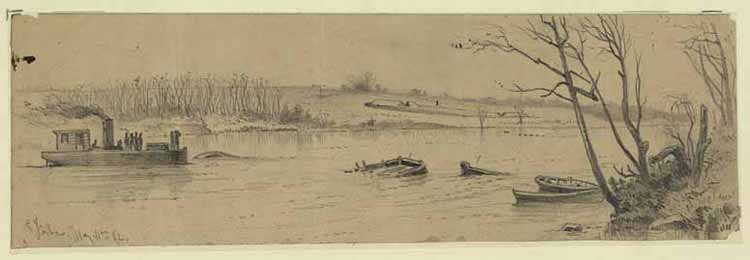

Remains of Burnt Steamers & Sailing Vessels on the Rappahannock River; May 6th 1862.

"Sunken Vessels in the Rappahannock River below Fredericksburg with Earthwork Commanding the Channel" dated May 11th 1862.

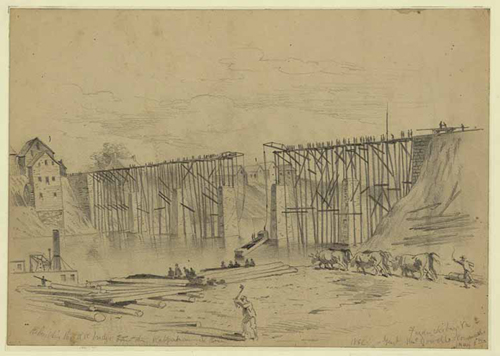

This

sketch dated May 6th 1862 is captioned, "Rebuilding the Railroad Bridge

over the Rapphannock River." Warren H. Freeman wrote home on May 18th,

"There

are the remains of three burnt bridges in view.

We have got the two pontoon bridges across

now, and there is a railroad bridge almost finished."

This

sketch dated May 6th 1862 is captioned, "Rebuilding the Railroad Bridge

over the Rapphannock River." Warren H. Freeman wrote home on May 18th,

"There

are the remains of three burnt bridges in view.

We have got the two pontoon bridges across

now, and there is a railroad bridge almost finished."

Loss of Sibley Tents and Camp Kettles

Saturday, May 24.

In heavy marching order we marched out

on

the road to Belle Plain Landing, seven miles, in the mud, and halted in

the rain for an hour, and then returned to camp in a cold, drenching

rain, to find our “Sibley” tents had been removed and piles of

“shelter” tents distributed about, to take their places.

We were wet through already, and muddy to the knees, so that when this transformation greeted us, the air in spite of the rain assumed a cerulean hue. He who couldn't swear

"Gave to mis'ry (all he had) a tear."

A worse day for such a sudden change could not have been selected. To apprecieate it one should bear in mind the description of a "Sibley" already given. In place thereof we received a piece of thin sheeting about four feet by six feet, in the binding of which were buttons and buttonholes. Each man was given one piece, with instructions to find two other men supplied with a similar piece, and combine the three into a tent. In order to pitch your tent you must first go into the woods and cut crotches with a stick to rest across the top, forming a ridge-pole, on which two of the pieces, buttoned together, were to rest, then to be stretched out in the shape of the letter A and fastened to the ground. The third piece was to cover one end. By making a combination of six pieces both ends could be closed. When properly pitched the ridge-pole was about four feet high. To enter one of these "dog-kennels," as they were called, you had to get down on your knees, with your head near the earth, as though you were approaching the throne of an Arabian monarch, and crawl in. Each man was expected to carry his piece of tent in his knapack. After we had become accustomed to the change, which we did by the exercise of a little patience and ingenuity, we found them not so very uncomfortable, but in the meantime we scored another mark against McDowell. The officers, whose tents had been taken away, were compelled to seek shelter among the rank and file. The officers' tents were subsequently returned.

It was at this place we were dispossessed of our camp kettles, a loss which carried with it another privation - rice. Rice was occasionally substituted for some other article of food, and was cooked in iron kettles previously used for making coffee. Good housekeepers have expended a deal of care and trouble in the preparation of this nutritous article of diet for the table, but in the army it was allowed to be burnt black for about three inches from the bottom of the kettle, thereby imparting to it a peculiar flavor. Since the war we have had no fondness for boiled rice; we miss that burnt taste and the delicate flavor of coffee with which it was permeated. No; when rice is now handed round the table we say, as Mark Twain did, "We pass."

The Change in Plans

At this time a plan had been adopted by which McDowell was to cooperate with McClellan. It was understood that McDowell was to move his corps along the Fredericksburg and Richmond Railroad on the 24th of May, connecting, if possible, with the right wing of McClellan’s army at or near Hanover Court-House, and by turning the left flank of the enemy, prevent his receiving reinforcements from the direction of Gordonsville. This plan had been carefully considered and matured by McDowell, who had great faith in its success, as appears in his correspondence with the President at this time.

At this date General McDowell’s army was composed of about 40,000 men, in as perfect a condition, respecting discipline and equipment, as any army acquired during the entire war. A finer body of troops, in health, vigor and appearance was never seen, and General McDowell was justly proud of his command.

Just at the moment when this army was concentrated, and about to take up its line of march to Richmond, as he notified McClellan he would do on the 24th, news was received at Washington of an attack on Banks by Stonewall Jackson, subsequently reinforced by Ewell, detached from Lee’s army. The suddenness of this intelligence created the wildest alarm among the authorities for the safety of that city, and the following order was telegraphed by the President to General McDowell, dated May 24, 5 P.M.:

General Fremont has been ordered by telegraph to move from Franklin on Harrisonburg to relieve General Banks, and capture or destroy Jackson’s and Ewell’s forces.

You are instructed, laying aside for the present the movement on Richmond, to put 20,000 men in motion at once for the Shenandoah, moving on the line, or in advance of the line, of the Manassas Gap Railroad. Your object will be to capture the forces of Jackson and Ewell, either in cooperation with General Fremont, or in case want of supplies or of transportation interferes with his movements. It is believed that the force with which you move will be sufficient to accomplish this object alone. The information thus far received here makes it probably that if the enemy operate actively against General Banks, you will not be able to count upon much assistance from him, but may even have to release him.

Reports received this moment are that Banks is fighting with Ewell, eight miles from Winchester.

(Signed)

A. Lincoln.

Though he obeyed the order with commendable alacrity, his disappointment at the sudden upsetting of a plan upon which his mind was fixed, was very great, as will be seen by the following communication to the President:

Headquarters Department of the

Rappahannock,

Opposite Fredericksburg, May 24, 1862.

(Received 9:30 P.M.)

His Exellency the President:

I obeyed your order immediately, for it was positive and urgent, and perhaps as a subordinate, there I ought ot stop; but I trust I may be allowed to say something in relation to the subject, especially in view of your remark, that everything now depends upon the celerity and vigor of my movements. I beg to say that cooperation between General Fremont and myself to cut Jackson and Ewell there is not to be counted upon, even if it is not a practical impossibility. Next, I am entirely beyond helping distance of General Banks; no celerity or vigor will avail so far as he is concerned. Next, that by a glance at the map, it will be seen that the line of retreat of the enemy's forces up the valley is shorter than mine to go against him. It will take a weeek or ten days for the force to get to the valley by the route which will give it food and forage, and by that time the enemy will have retired. I shall gain nothing for you there, and shall lose much for you here. It is, therefore, not only on personal grounds that I have a heavy heart in the matter, but that I feel it throws us all back, and from Richmond north we shall have all our large masses paralyzed, and shall have to repeat what we have just accomplished. I have ordered General Shields to commence the movement by to-morrow morning. A second division will follow in the afternoon. Did I understand you aright, that you wished that I personally should accompany this expedition? I hope to see Governor Chase to-night and express myself more fully to him.

Very respectfully,

Irvin McDowell.

Departure for the Shenandoah Valley

Sunday, May 25.

Sunday, May 25.

About 4 P.M. we marched to Aquia Creek,

fifteen miles, arriving about 1

A.M. The road, part of the way, was a cross a swamp, so that

candles were lighted to prevent our tumbling into ditches. On the 26th

we continued our march four miles, to the landing where the Thirteenth

took the steamer “John Brooks” for Alexandria, and where we arrived in

due time, after a sail of sixty-five miles up the Potomac River.

Other

similar means of transportation were provided for the remainder of the

division. The severe drilling we had been undergoing, the change of

tents and reduction of baggage, all indicated that some important

movement was on the tapis, which camp gossips had determined was “on to

Richmond.” We were very much surprised, as we sailed up the

Potomac, to learn that it was “on to Washington,” for, as yet, we had

not received information about Banks’ retreat. Whatever fate

had in store for us, it didn't interfere with our enjoyment of the

sail, though our curiousity was greatly excited to know what this

movement meant.

In a letter to McClellan dated May 25, the President gives a full statement of the situation, closing with the following paragraphs, which he puts in italics:

If McDowell's force was now beyond our reach, we

should be entirely

helpless. Apprehension of something like this, and not

unwilingness to sustain you, has always been my reason for withholding

McDowell's forces from you.

Please understand this, and do the best you can with the forces you

have.

Tuesday, May 27.

We were routed out at 3 A.M., and

marched to the station in Alexandria,

where, after waiting patiently for two hours, we boarded freight cars

for Manassas Junction. Some of the boys succeeded in

procuring local newspapers, by which we became partially informed of

the excitement. The necessity of feeling our way, as we rode

along,

delayed our arrival until the afternoon. We were soon in possession of

Northern papers that gave us full particulars of Banks’ movements, and

lively discussions round camp-fires ensued, ending in a generally

expressed hope that we might take a hand in bagging Jackson.

Wednesday, May 28.

Orders received that shovels, pickaxes,

etc., were to be carried by the men instead of the wagons, as

heretofore. This caused a good deal of grumbling.

In addition we were to carry sixty rounds of cartridges, fifty in the

boxes and ten in our haversacks. Our prejudices having been

excited against McDowell, we promptly placed this disagreeable order

with the others, to his credit.

© Bradley M. Forbush, 2009

Page Updated December 29, 2009.